Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Bradley Cooper conducts a moving new Leonard Bernstein biopic.

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

Maestro, directed by Bradley Cooper,

opening in select theaters November 22, 2023

• • •

Even when they don’t entirely succeed, Bradley Cooper’s films are too big to fail. Not so long ago, he was simply a middling, hammy actor, best known for playing one of the libertines in The Hangover (2009) and as a regular in the manic ensemble casts of David O. Russell’s screwball tragicomedies of the 2010s. But the release in 2018 of A Star Is Born, his directorial debut—which he also cowrote and, acting opposite Lady Gaga, headlined—signaled a commitment to making serious, overwhelming cinema, an aim I couldn’t help but admire. Reviewing A Star Is Born for 4Columns, I called it “engorged with ambition,” words I meant as praise, even if that zeal couldn’t always compensate for the dopey homilies that litter the script. Whatever the movie’s flaws, though, Cooper brought throbbing life to a typically necrotic genre, the remake—a feat all the more impressive considering that his was the fifth iteration of one of cinema’s most enduring meta-myths.

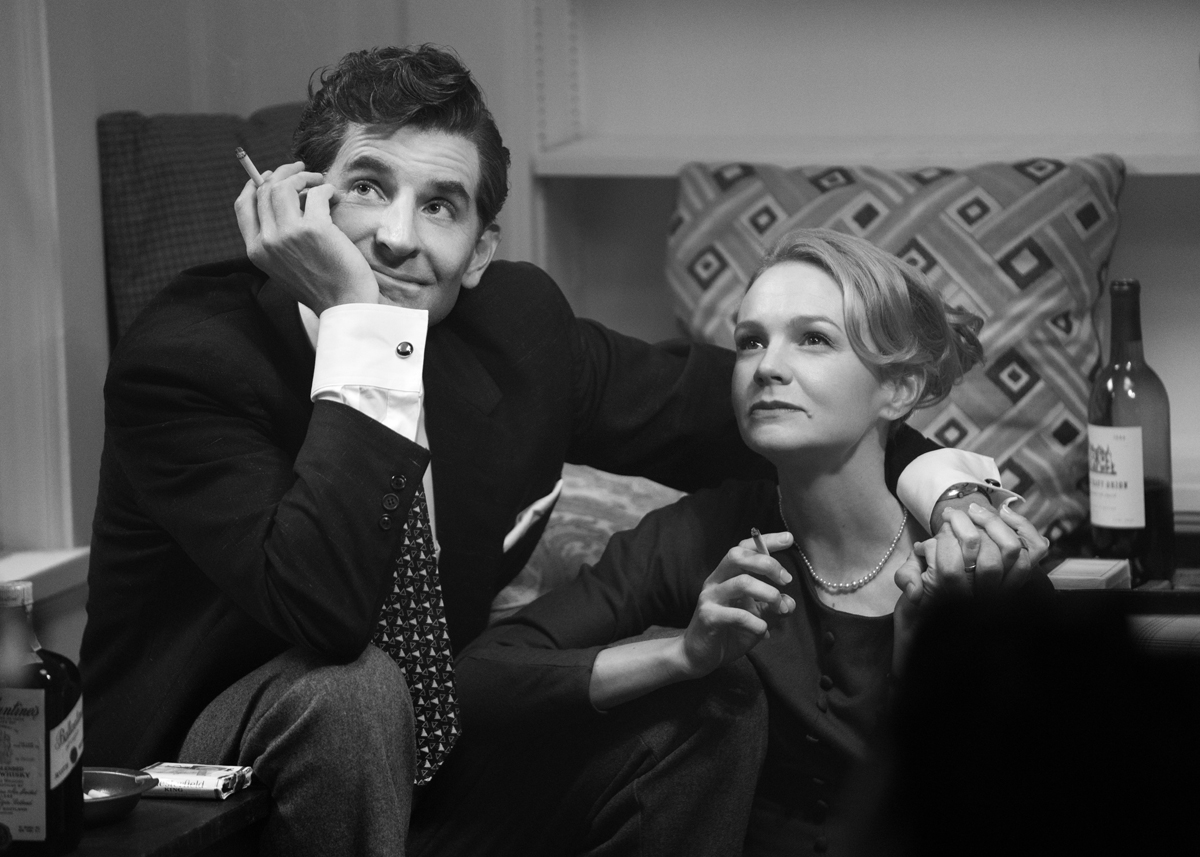

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein and Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

Now, with Maestro, his second film, for which he once again pulls triple-duty, Cooper performs CPR on the biopic, another enfeebled genre. And the life he has chosen to bring to the screen and to inhabit, from a script he cowrote with Josh Singer, is that of a polymathic colossus of postwar American music and culture, Leonard Bernstein, a man with enormous charisma, drive, and energy. To give his gargantuan project a manageable focus, Cooper concentrates primarily on Bernstein’s relationship with the stage and television actress Felicia Montealegre (played by Carey Mulligan), whom he first met in 1946 and wed in 1951, a union that produced three children and that lasted (with a few rifts) until her death, in 1978. In many ways loving, theirs was a marriage fissured by one intractable complication: Bernstein’s homosexuality. Maestro excels when examining its leads’ most acute emotional states, namely the musician’s boundless enthusiasms (for creating, for men, for his family) and his spouse’s self-reproach over her conjugal compromises. Like many biopics, though, it falters and distracts when it becomes too obsessively focused on superficial mimesis.

Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

Specifically, Cooper’s determination to look like Bernstein throughout the decades has resulted in some ghastly facial special effects. The first scene of Maestro, in fact, nearly put me off the whole movie: the conductor, near the end of his life (he died in 1990, at age seventy-two), is seated at a piano bench, talking about his love for Felicia to a documentary crew. This hokey prologue becomes even more disastrous when the initial dorsal view of the eminence segues to the frontal; buried under prosthetics, Cooper-as-Bernstein resembles nothing so much as one of the geriatric miscreants in Harmony Korine’s deliberately artless Trash Humpers. (Cooper’s errant perfectionism was also evident in his strenuous, ultimately futile effort to lower his voice an octave for A Star Is Born.)

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

But that inauspicious opening is immediately followed by an exhilarating segment: a twenty-five-year-old Bernstein receiving the phone call that would change his life. Roused from sleep, the outline of another, mostly illegible body next to him in his darkened bedroom, he is told that he will have to fill in at the last minute for an ailing guest conductor and lead the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall that afternoon without a rehearsal. “You got it, boy!” he crows; throwing the curtain open, he punctuates his exultation by playfully slapping the butt of his now visible lover, clarinetist David Oppenheim (Matt Bomer). With fluid camera movements and a quick succession of cuts, we soon witness a beaming, tuxedoed Bernstein after his triumphant debut in 1943 at the legendary concert venue. A star is born.

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein and Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

This sequence and the roughly fifty minutes that follow, all shot in silky black-and-white, stand as Maestro’s strongest, with Cooper astutely distilling Bernstein in fervid collaboration with other mid-century homosexual geniuses (Aaron Copland, Jerome Robbins), mondaine parties, the rush of his early courtship with Felicia, the tragedy of the closet. “I know exactly who you are,” Felicia tells her swain before they tie the knot; that piercing adverb nicely encapsulates a welter of conflicting thoughts: her full knowledge of her soon-to-be spouse’s sexuality, her ardent belief that this will have no bearing on her happiness with him. (The line reflects Felicia’s wrenching sentiments in a letter she wrote her husband shortly after they wed: “You are a homosexual and may never change—you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? . . . I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the L. B. altar. . . . Our marriage is not based on passion but on tenderness and mutual respect. Why not have them?”)

Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre and Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

Maestro, especially in its first half, affectingly depicts the core contradiction of the Bernsteins’ relationship by showing, not telling. In one fantastical sequence, the couple, defying laws of time and space, appear on a stage where Fancy Free—the 1944 ballet of three sailors on shore leave composed by Bernstein and choreographed by Robbins that served as forerunner for the exuberant musical On the Town—is being performed. A Paul Cadmus painting come to life, the dance dazzles with its homoerotic élan. Bernstein’s indispensable contribution to this libidinal opus is amplified by another bit of magical realism, showing the composer as one of those horny, leaping seamen; Felicia, while avidly looking on, also evinces more than a hint of terror. In fact, for a film devoted to the glorious sounds created by its title character, Maestro is at its best when chaotic feeling is expressed silently, as in the exchange of knowing glances between David and Felicia when Bernstein introduces his fiancée to his one-time boyfriend and, later, when they are both married and fathers, in the rueful stares between the two men during a chance encounter on the street.

Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre and Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

When the film shifts from black-and-white to color—a jump of roughly twenty years, to the early ’70s, when Bernstein is at the zenith of his global iconicity and his marriage nearing its nadir—the dialogue of the voluble couple curdles into too-rote volleys of recriminations. “If you’re not careful, you’re going to die a lonely old queen,” Felicia venomously declares to her husband, who’s been flouting her request for “discretion” with his latest inamorato, Tommy Cothran (Gideon Glick). These showboating set pieces of domestic discord abrade not only the ears but also the eyes, since they mark the beginning of Cooper’s extreme transmogrification of his mug.

Isabel Leonard and Rosa Feola as Ely soloists and Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Jason McDonald.

But even in the midst of all this clamor, there is balm: Bernstein conducting Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony at England’s Ely Cathedral in 1973. Jumping up, lost in rapture while at the podium, Cooper movingly conveys the maestro’s animated conducting style—his gestures guiding the notes that create a fathomless depth of feeling, too big to put into words.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.