Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Call of the wild adaptation: Pietro Marcello reimagines Jack London’s 1909 novel.

Luca Marinelli as Martin Eden in Martin Eden. Image courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: © Francesca Errichiello.

Martin Eden, directed by Pietro Marcello, available to watch via

Kino Marquee

• • •

Unfathomably prolific, Jack London had a lust for life that could be mistaken for a death wish. In the forty years that he lived, from 1876 to 1916, the novelist, journalist, adventurer, and social activist wrote fifty books, many based on his vast experiences. His teenage exploits as an oyster pirate and a member of the California Fish Patrol inspired at least two novels; at age twenty-one he joined the Klondike gold rush, the setting for some of his best-known works, including The Call of the Wild (1903) and White Fang (1906).

Incessantly toiling, not least for literary glory, London essentially burned himself out, expiring mainly owing to illnesses he acquired during his relentless traveling (and his alcoholism). This monomaniacal zeal for artistic fame—and his immense dissatisfactions with it once it arrived—greatly informed London’s most autobiographical novel, Martin Eden (1909). In his brash, vivid adaptation of the Bay Area writer’s Künstlerroman, the Italian filmmaker Pietro Marcello has unmoored the text from its original country and era, boldly reimagining London’s alter ego as a Neapolitan seafarer in a deliberately imprecise time, roughly post–World War I to the 1970s.

Though Marcello’s project, which he cowrote with Maurizio Braucci, remains largely faithful to the major incidents and themes of London’s book, the film, unlike the source text, begins with a flash-forward, depicting the title character, played by Luca Marinelli, in a state of decline. With a sallow pallor and greasy, stringy, gray-flecked hair, Martin hunches over a reel-to-reel tape recorder, feebly puffing a cigarette. “So the world is stronger than me,” he murmurs into the microphone, an admission of defeat immediately contradicted by a self-aggrandizing declaration: “My force is fearsome as long as I have the power of my words to counter that of the world.”

Similarly, the next image of the none-too-subtly-named protagonist belies what we’ve just seen: a rugged, handsome, dashing young mariner—Martin Eden before the fall. But before we’re introduced to this hale Martin, outfitted in garments that suggest the ’40s or ’50s, Marcello further scrambles time, inserting century-old archival footage—of trains, crowds at a town square, and the Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta—and cuing up “Piccerè,” a downtempo Italo-pop track from 1979. These chronology-deranging interpolations occur throughout the film, either as documentary snippets of street life and labor scenes spanning several decades or as original 16mm footage shot by cinematographers Alessandro Abate and Francesco Di Giacomo that was then treated with various analog effects to evoke scenes of Martin’s childhood. (Inlays of archival footage are also a key element of Marcello’s The Mouth of the Wolf, an affecting docufiction from 2009 that salutes not only the crumbling grandeur of Genoa but also the long relationship of an ex-con and his transwoman lover.)

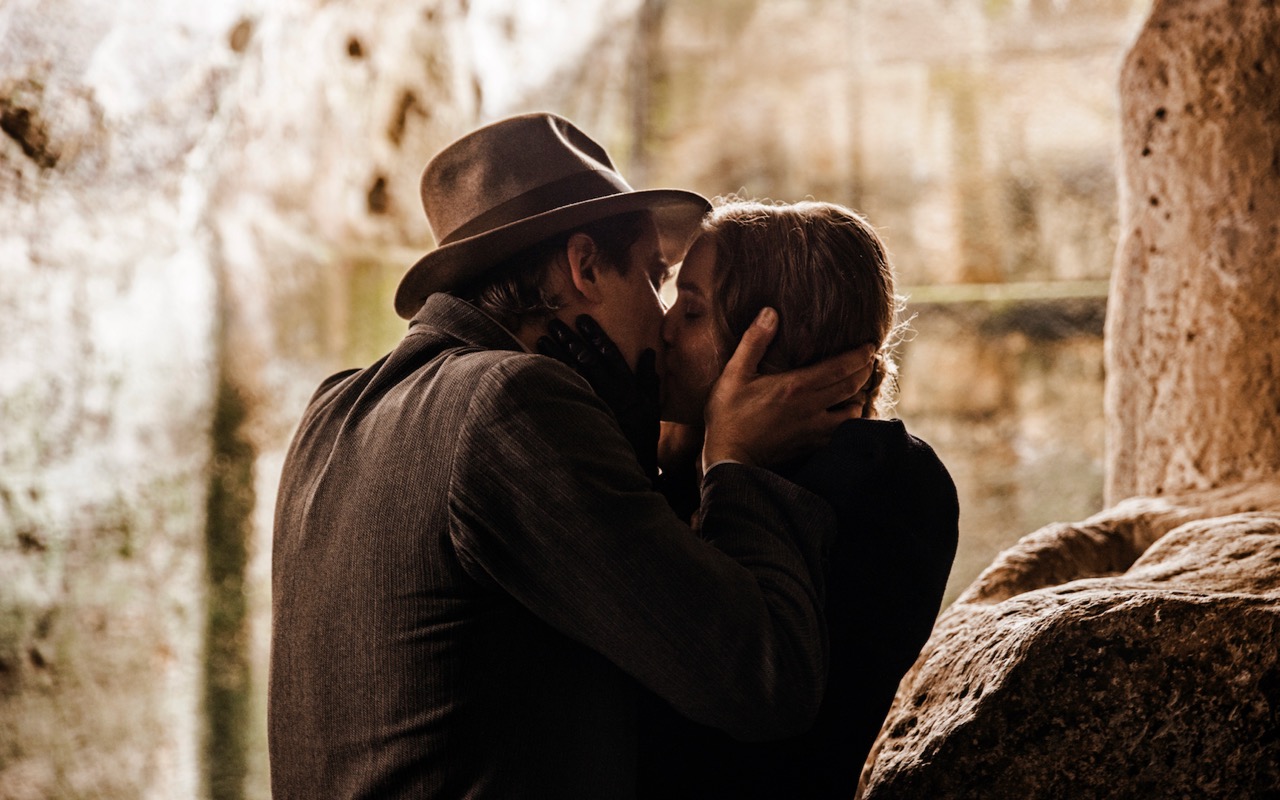

Luca Marinelli as Martin Eden and Jessica Cressy as Elena Orsini in Martin Eden. Image courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: © Francesca Errichiello.

Adrift in the twentieth century, movie Martin amply demonstrates that the struggles of London’s character, however rooted in the author’s own life and epoch, aren’t solely those of the Progressive era. Parentless and penurious, Martin finds that his greatest challenge ranks among the most enduring: advancing his social status. After rescuing a puny toff named Arturo Orsini (Giustiniano Alpi) from being pummeled, Martin is feted by the fop’s family to thank him for his bravery. At casa Orsini, he falls instantly in love with Arturo’s sister, Elena (Jessica Cressy), a porcelain beauty who corrects Martin’s pronunciation of “Baudelaire” and lends him two books. To prove his worthiness to the young woman who is touched by his devotion to her but still takes small, sadistic pleasure in pointing out his grammatical errors, Martin becomes an inexhaustible autodidact, determined to succeed in that most exalted of professions, writing.

Luca Marinelli as Martin Eden and Jessica Cressy as Elena Orsini in Martin Eden. Image courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: © Francesca Errichiello.

“I ask you to give me two years to prove my talent,” Martin pleads to his ever-dubious beloved, who insists he’d be better off asking her father to secure him a dull clerical position. With potent economy, Marcello dramatizes Martin’s tireless drive, the depiction of which in London’s novel accounts for the majority of its nearly five hundred pages and is here abbreviated to the constant clacking of typewriter keys and the sight of innumerable pages clipped to clotheslines and stacks of Martin’s manuscripts being returned to him, unopened, almost as quickly as they’re mailed out.

Yet when Martin’s unyielding efforts are finally rewarded, his success provides little satisfaction. He’s disgusted equally by the bourgeois pieties of the Orsinis and the collectivist credos of a mentor, espousing instead the social Darwinism of Herbert Spencer. (That nineteenth-century English philosopher also fascinated Jack London, whose radical socialism sometimes mixed uneasily with his beliefs, mirrored in Martin’s, in the supremacy of the individual.) But Martin’s greatest contempt is for the masses now reading his books, memorably described by London as “a wolf-rabble that fawned on him instead of fanging him. Fawn or fang, it was all a matter of chance.”

This desiccated Martin, who’s first glimpsed in the film’s opening scene and dominates its final quarter, calls to mind one of the etiolated maestros in the oeuvre of Luchino Visconti, such as Dirk Bogarde’s von Aschenbach in Death in Venice (1971). Conversely, pre-celebrity Martin suggests a neorealist paragon, like the desperate father played by Lamberto Maggiorani in Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948). By deftly summoning touchstones of Italian cinema, Marcello adds to the pleasing anachronisms of this epic tale, a study of a larger-than-life character whose grandness is magnified by the brio of Marinelli’s performance.

Luca Marinelli as Martin Eden and Jessica Cressy as Elena Orsini in Martin Eden. Image courtesy Kino Lorber. Photo: © Francesca Errichiello.

Marcello’s adroit interventions in London’s text liberate the spectator to imagine other fantastical additions. I first saw Martin Eden in the fall of 2019, when it screened in advance of its New York Film Festival premiere at the Walter Reade Theater—where, in the late ’90s and early ’00s, I would often see Susan Sontag. As it happens, Sontag, who first read London’s novel when she was twelve, would long consider the book an “awakening,” invaluable in preparing her for the arduousness of the writer’s life by “preach[ing] despair + defeat,” as she wrote in her journal in 1950. Watching Marcello’s reimagining of London’s parable on an enormous screen, I wondered what Sontag’s response to this free interpretation would be. But more pleasurably, I envisioned another Martin Eden adaptation entirely: one that could double as a stealth Sontag biopic, a film that traces the triumphs and agonies of a woman who reigned as the leading cultural authority for the second half of the twentieth century.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.