Erika Balsom

Erika Balsom

Before there was Valley Girl, Martha Coolidge’s 1975 debut film presented a very different portrayal of high school teens.

Michele Manenti and Martha Coolidge in Not a Pretty Picture. Courtesy Picture Pro LLC / Janus Films.

Not a Pretty Picture, directed by Martha Coolidge, playing February 2–8, 2024, Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City

• • •

The title of Molly Haskell’s 1974 book From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies lays it out with stark clarity: classical Hollywood runs on sexual violence. From as early as Birth of a Nation (1915), it is there as a narrative motor, humming with pleasure and fear. Within the constraints of the Hays Code, however, actual rape was but a latent presence, if implied at all. In King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946), for instance, Pearl’s encounters with the lecherous Lewt are depicted as an ambiguous tangle of his aggression and her submission to repressed desire, with the act itself elided by lightning seen through a windowpane. Ida Lupino’s Outrage (1950) stands as an exceedingly rare instance in classical Hollywood of a film centered on the experience of sexual assault, but even there the pivotal event occurs in the abyss of a cut, and “rape” is never uttered. Haskell’s use of the word in her title is thus best understood as not entirely literal, but as a metonym for Hollywood’s more general predilection for the subordination of women. Yet it is also indicative of something else: how thoroughly sexual violence had become a key site of feminist activism by the mid-1970s. As authors such as Susan Brownmiller emphasized that marital rape and date rape were, in fact, rape, familiar experiences and images—such as those in Duel in the Sun—could be seen through a new lens.

Still from Not a Pretty Picture. Courtesy Picture Pro LLC / Janus Films.

This sea change was not lost on independent filmmakers. There were new images to be made and stories to be told. The hope was that silence and shame would belong to yesterday, both in life and at the movies. Mitchell Block’s faux vérité No Lies (1973) and JoAnn Elam’s experimental documentary Rape (1975), short films in which women recount experiences of sexual violence, stand as two important titles from this moment. But perhaps the most notable entry in this cycle is Martha Coolidge’s Not a Pretty Picture (1975), the newly restored debut feature by a director better known for the more conventional and commercial path she took subsequently with Valley Girl (1983).

Michele Manenti in Not a Pretty Picture. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

Released just after the success of Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), Valley Girl doubled down on Heckerling’s wager that a woman’s best chance at making it in Hollywood was to helm a teen movie. With a candy-colored palette and a young Nicolas Cage in the role of a gentle punk from Hollywood High, this riff on Romeo and Juliet tells the tale of young lovers who transcend the petty concerns of class and clique. It’s a pretty picture. Not a Pretty Picture gives a very different account of high-school heterosexuality, one not coincidentally made on a much smaller budget and across the documentary/fiction divide. Based on Coolidge’s own life, this hybrid film twists the tropes of the coming-of-age story to offer an unprecedented account of date rape and its aftermath from the perspective of a survivor.

Jim Carrington and Michele Manenti in Not a Pretty Picture. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

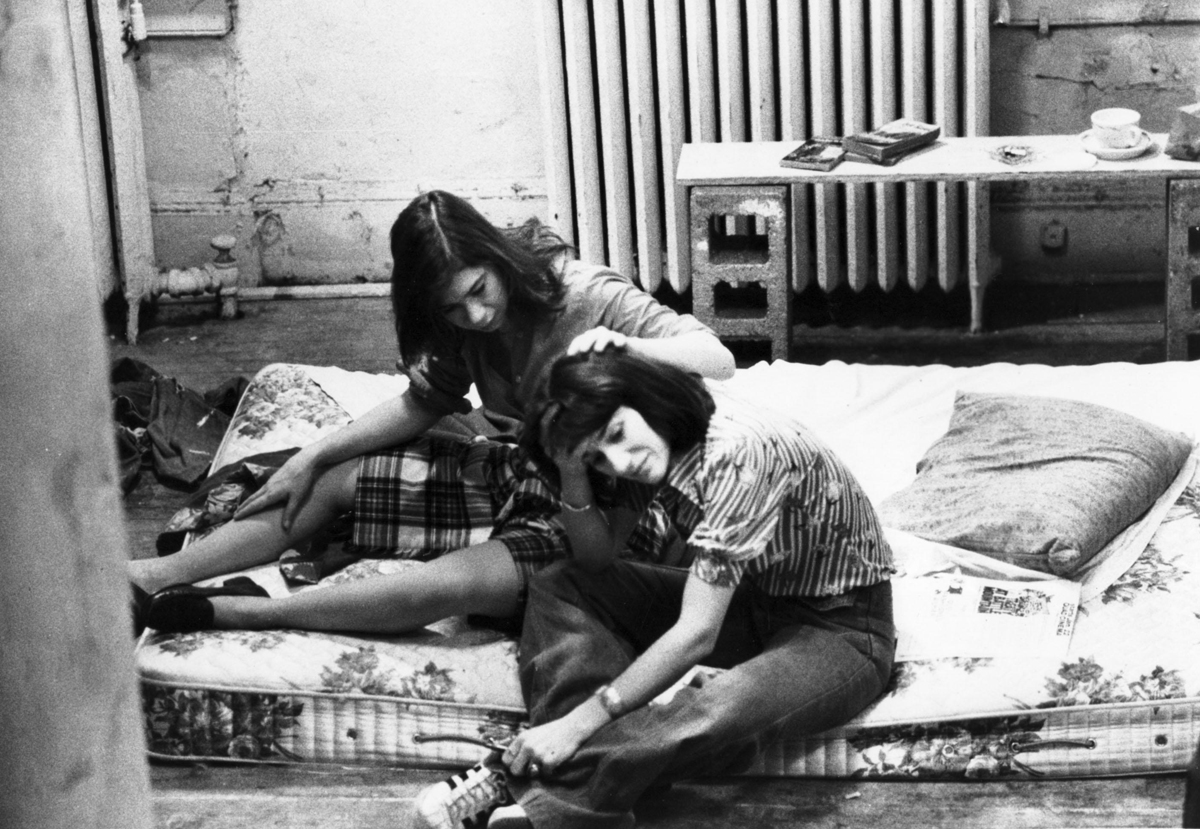

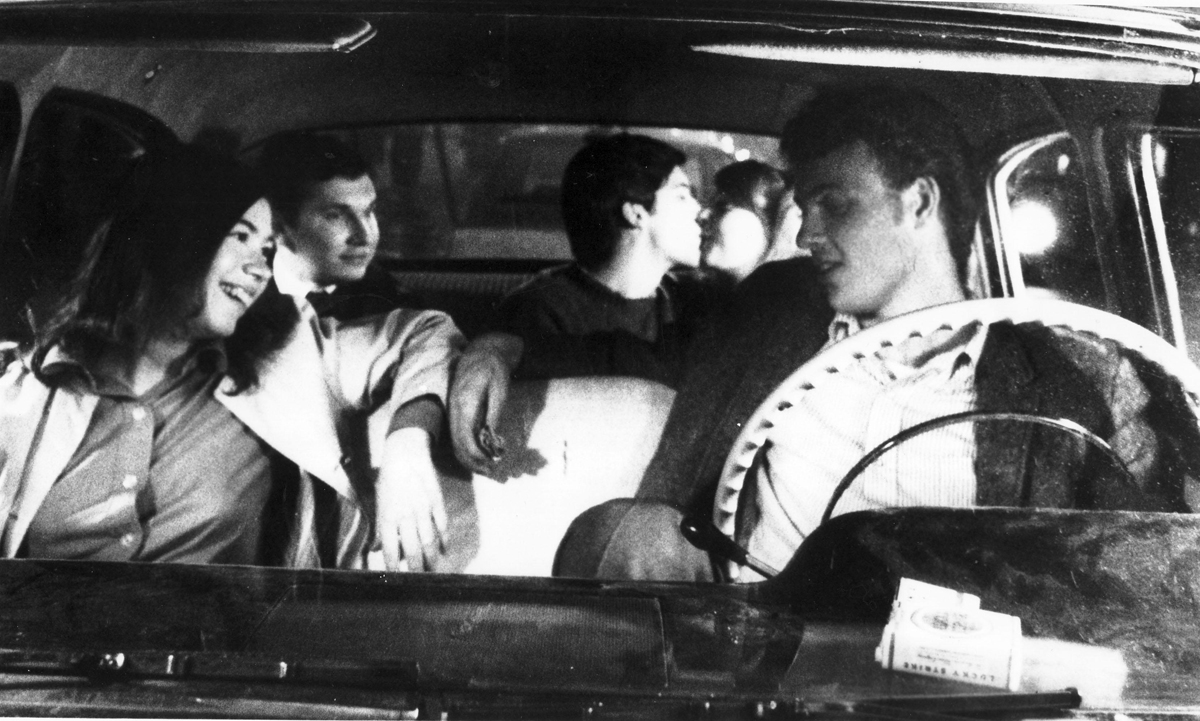

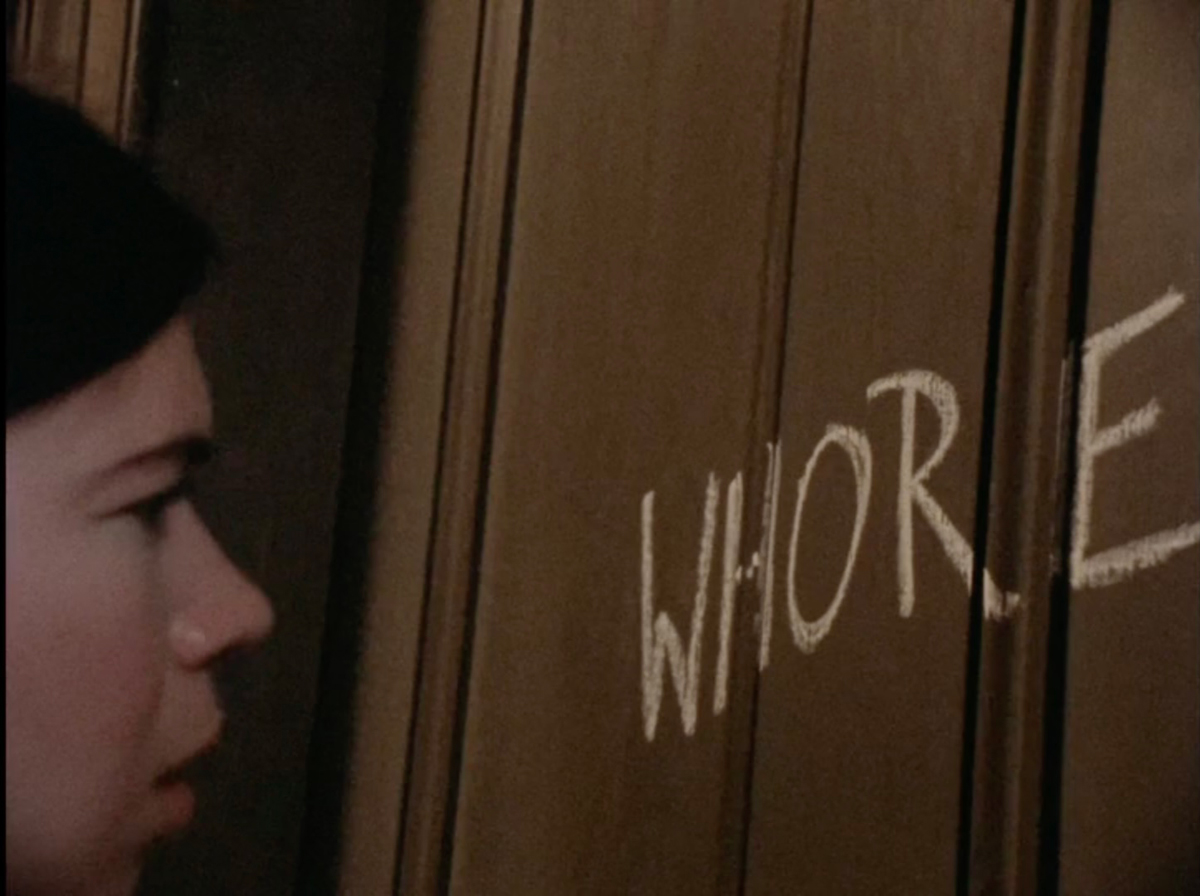

Not a Pretty Picture combines dramatizations, set in 1962, of Coolidge’s rape with documentary sequences of the production process and interviews with cast members who discuss the reenactments in relation to their own lives. The fiction finds Martha (Michele Manenti, herself a rape survivor) at age sixteen, on a night out with a dorm-mate and some boys, including the twenty-one-year-old Curly (Jim Carrington). A promise of a party turns into a night in an empty apartment, where Curly forces himself on Martha. Back at school, rumors fly and cruelty abounds. Girls call Martha a whore. The closest thing to a happy ending here is that she escapes pregnancy and finds support in Anne, played by Coolidge’s real high-school best friend, Anne Mundstuk. The behind-the-scenes material, largely shot in the run-down loft where the fictional rape takes place, cuts through the cloying artifice of these teenybopper vignettes, injecting frank disclosures in the tradition of feminist consciousness-raising and the many films of the early 1970s that drew upon that practice. What emerges is not simply an alternation between the staged and unstaged; different epochs and relationships to knowledge collide, as Coolidge juxtaposes the naivete of her earlier self (who did not come to understand her experience as rape until age twenty) with the analytical capacities she and others had developed since, in the wake of the second wave. American Graffiti (1973) looked back at 1962 with rosy nostalgia; just two years later, Not a Pretty Picture looked back at that same time, finding in it pain, shame, and ignorance. The good old days weren’t good for everyone.

Michele Manenti in Not a Pretty Picture. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

It might sound like Not a Pretty Picture is sharply bifurcated. Mostly, it is. Yet as the film approaches the assault, the fiction veers toward a more naturalistic style, as if to acknowledge the hackneyed codes of the coming-of-age film are insufficient and a different language is needed, one that would break with euphemism and voyeurism. During the rape, the boundary between 1975 and 1962—between the film and the film-within-the-film—begins to dissolve. The camera, now handheld, starts to move erratically, catching a glimpse of the crew. It pans between the rape and Coolidge, who looks on in rapt, slightly horrified, absorption, the back of her hand pressed to her mouth. The past lives in the present. The two axes of the film briefly conjoin, before separating again.

Martha Coolidge in Not a Pretty Picture. Courtesy Picture Pro LLC / Janus Films.

In one respect, Coolidge’s documentary sequences throw into relief the treachery of the fiction. Her depictions of an era habitually presumed to have been more innocent than her present are veiled in irony. If they grate, if they feel stilted and false—and they often do—all the better. But conversely, the fiction disrupts any impression of documentary immediacy and foregrounds the problem of representation. It acts on reality by catalyzing conversation. Its creation is a way of reclaiming power, of becoming she who acts rather than she who is acted upon. These days, you can’t throw a stone without hitting a documentary that uses reenactment, which wasn’t the case in 1975. But unlike so many recent works—The Act of Killing (2012), to mention only the most famous—that suggest the therapeutic value of this technique for participants tasked with working through trauma, there is no hint that Coolidge made Not a Pretty Picture to heal herself or her lead actress, even if the film does conclude with the director’s avowal that she remains afraid and has continuing problems with trust. The aim here is to end the monopoly of pretty pictures, to clear a space for the candid depiction and discussion of sexual violence at a time when that was just starting to gain ground in the public sphere. It is an autobiography stripped of narcissism, a gift from one woman to all.

Erika Balsom is a Reader in Film Studies at King’s College London. Most recently, she is the coeditor of Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image, published by MIT Press.