Hannah Black

Hannah Black

A New Museum show of Black art finds itself frozen in time.

Theaster Gates, Gone Are the Days of Shelter and Martyr, 2014. Video, sound, color; 6:31 minutes. © Theaster Gates. Courtesy White Cube and Regen Projects.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, conceived by Okwui Enwezor, with curatorial advisors Naomi Beckwith, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash, and with Massimiliano Gioni, New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through June 6, 2021

• • •

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, now on view at the New Museum, was devised in 2018 by the late curator Okwui Enwezor, who died in 2019 before he could complete his work on the show. Conceived as a rejoinder to Trump’s mobilization of white grievance, the thirty-seven-person exhibition was meant to open during the 2020 presidential election campaign. Instead, it lands in the extended pause of early 2021, with Trump abruptly gone and the new administration still feeling like little more than the blank space where he used to be. The other crucial absence—Enwezor’s—makes the show a memorial whose final shape was determined by his colleagues (a curatorial advisory team made up of Glenn Ligon, Mark Nash, and Naomi Beckwith), leaving space to wonder what might otherwise have been.

Enwezor was struck by Trump’s use of Gettysburg—site of Lincoln’s address—as a backdrop for a 2016 campaign rally. According to a museum wall text he wrote before his death, the rally attempted to superimpose Trump’s white nationalism over the complex historical interstice of the Civil War. In response, Enwezor was moved to plan a reflection into “the crystallization of black grief in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance.”

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Procession, 1986.

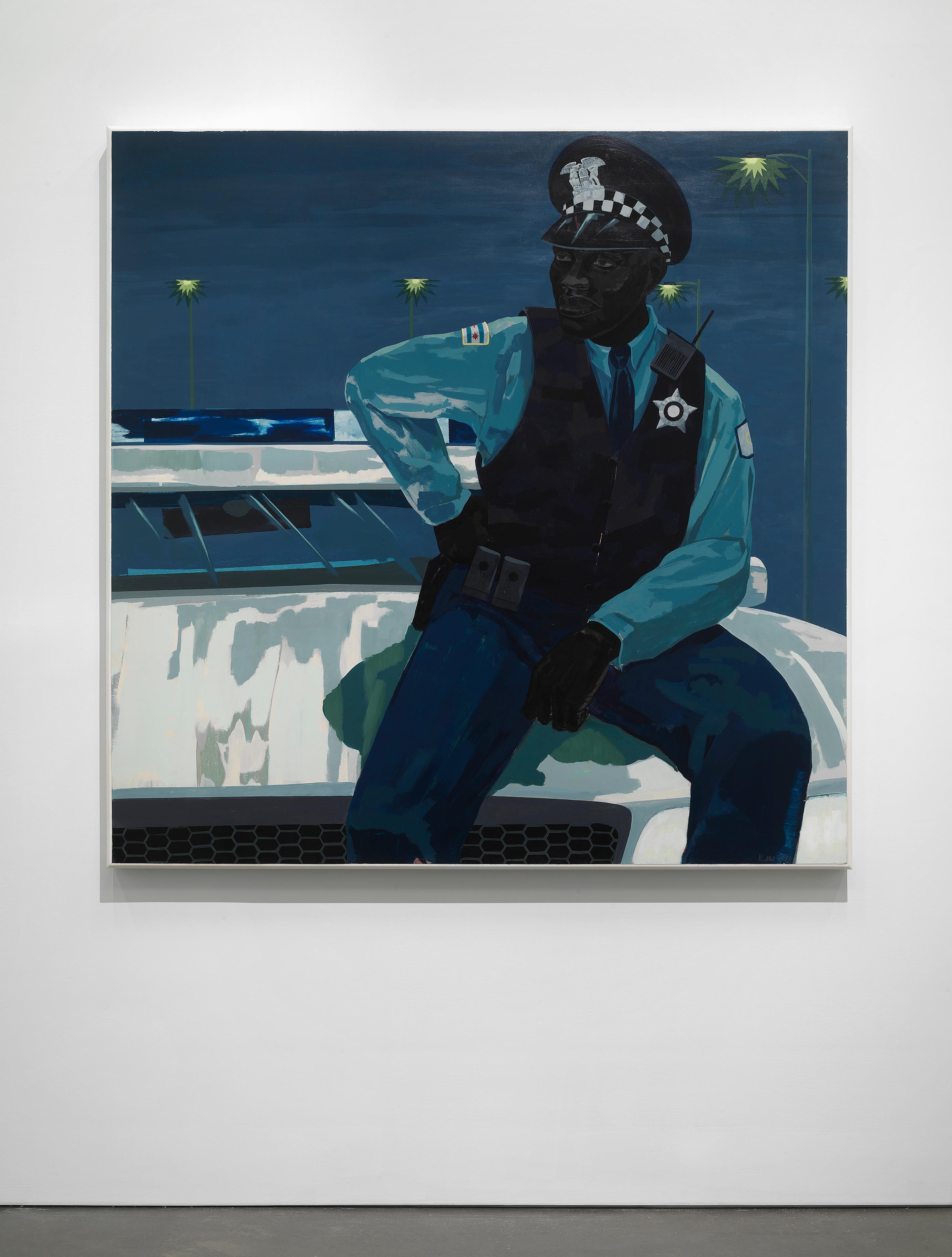

Two paintings hang on opposite sides of the wall across from the third-floor entrance. First, facing the elevator, the still-fresh impact of Basquiat’s Procession (1986), with a curatorial note highlighting his response to the 1983 murder of artist Michael Stewart by the NYPD. Around the other side of the wall, back-to-back with Basquiat, is Kerry James Marshall’s quiet Untitled (policeman), a 2015 depiction of a black cop. This invocation of two contemporary political ur-figures, black police victim and black cop, is a conceptual keystone in this worthy but pedestrian review of mostly American, mostly recent black art framed by the concept of black grief. The grievance of the title, Enwezor’s text suggests, is white and not imaged in the show.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (policeman), 2015.

Grief here sometimes refers to specific loss, such as in LaToya Ruby Frazier’s clear-eyed portraits of her family, who have since died or been transformed by time, or Kahlil Joseph’s meandering video of a musical improvisation, made shortly after the death of his brother, Noah Davis. Grief is also posited as a social condition: “The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning,” as the title of the Claudia Rankine catalog essay puts it. Although the two terms are often used interchangeably, mourning, suggesting a social praxis, is not exactly the same as grief, which is the uncooked pain of loss. It may even be that the “grief” of the show’s title, with its implication of retrospect, is the wrong register for the ongoing disaster of US anti-blackness. In any case, the exhibition’s account is lacking grief’s more active parts: denial, bargaining, anger. Despite Enwezor’s evident desire to respond to the zeitgeist, there is not one thing in this exhibition that lets on that it opens well under a year since the biggest mass protests against anti-black police violence in US history. The curatorial intention, frozen by Enwezor’s death, could not adjust to meet a new moment.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Kara Walker, Book of Hours and Book of Hours (ICBM’s for HCBU’s), both 2020.

Depression and acceptance are highlighted instead. Theaster Gates’s hypnotic video of a black monastic order of musicians ritually smashing up a ruined church conveys the strange beauty of urban decay, a heartfelt scene whose accidental convergence with gentrification narratives that recast inner-city dilapidation as an edgy urban aesthetic is not exactly the artist’s fault. Exceptions to the exhibition’s somber mood include a series of magnetically on-form Kara Walker drawings and Diamond Stingily’s freestanding doors paired with baseball bats. Walker’s drawings evoke black grievance rather than grief, a tonal shift that emphasizes how little the mournful framework suits her bracing coldness, Stingily’s careful warmth, or even, really, an exhibition that aims to respond robustly to white supremacy.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Diamond Stingily, Entryways, 2016; Entryways, 2016; and Entryways, 2019.

The show focuses on black American life/death, though a video installation by artist/choreographer Okwui Okpokwasili references Boko Haram and the 1929 Women’s War in Nigeria. The work lacks the intensity of her performances, but at least it provides an unexpected moment. Beyond that, there are no surprises. Basquiat, Walker, Marshall, Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson: the curatorial strategy copies the all-time-hits editing logic of Arthur Jafa’s Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016), on view on the first floor. Both exhibition and video include many interesting and beautiful things, but while the video is like a love poem in its exhilarating play with corniness, the exhibition leans toward rote overview. This may be simply a symptom of the change in era; the same collection of artworks may well have felt fresher a couple of years ago, or defiant under a second Trump term.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Arthur Jafa, Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016.

Some juxtapositions of artists feel instructive, if at times leaning hard on a simplistic though pretty color-matching strategy. The vivid blue of a Simpson print rhymes pleasantly with a series of turquoise-dominated Ellen Gallagher paintings, helping both resist being upstaged by Walker in the same room. In a monochrome zone on the first floor, Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s deeply eerie jet-black cattle stall stands by a wall of X-ray photographs of ghostly objects by Terry Adkins, and a moving black-and-white film by Garrett Bradley that documents a love story harrowed by incarceration.

Garrett Bradley, Alone, 2017 (still). Single-channel 35mm film transferred to video, sound, black and white; 13 minutes. © Garrett Bradley. Courtesy the artist.

The absence of color in Bradley’s film makes our glimpse into the life of its subject, Bradley’s friend Aloné Watts, both more romantic and more restrained—as if the black and white draped a loving veil over the intensity of her experience. When she waits outside prison for a moment of eye contact with her beloved as he walks in stripes and zip ties, the camera is at an angle, reflecting a world absolutely awry. The painful coexistence of the gray melancholy of grief with the spikier affects of ongoing oppression is brought to light in the film in a way that the exhibition as a whole does not quite manage.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured, left, on wall: Julie Mehretu, Black Monolith, for Okwui Enwezor (Charlottesville), 2017–20, and Oceanic Beloved (A.C.), 2017–18; center of room: Rashid Johnson, Antoine’s Organ, 2016.

On the fourth floor, big expensive-looking Julie Mehretu paintings complement Rashid Johnson’s spectacular Antoine’s Organ (2016). Johnson surrounds a live piano player with a huge modular display of plants, TVs, speakers, and books, including multiple stacked copies of a novel by Paul Beatty titled The Sellout, a self-reflexive touch that the curatorial wall text notes blandly and in passing, perhaps because irony is considered incompatible with grief. Though the monumental nature of both Johnson’s and Mehretu’s work impresses, it feels like a missed opportunity for an exhibition purporting to investigate the fullness of black grief to cleave so closely to the valorizations of the art market.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured, left, suspended from ceiling: Kevin Beasley, Strange Fruit (Pair 1), 2015.

Grief and Grievance was partly inspired by Black Lives Matter’s astonishing deployment of grief as a politics, but there is no equivalent sense of urgency here. Again, circumstances are partly at fault: in Enwezor’s initial concept, performance work evoking physical presence was supposed to give the show a pulse, but COVID changed the music. Kevin Beasley’s sculpture Strange Fruit (Pair 1) (2015) is usually intended to mediate performance, but a curatorial note instead offers its silence as a gesture of plague-era respect. Despite its evident care and seriousness of purpose, Grief and Grievance’s focus on melancholy as preeminent black expression invites the question: Why hold a funeral for the living?

Hannah Black is an artist and writer from the UK. She lives in New York. She has previously written for Artforum, the New Inquiry, Afterall, and a number of other publications. Recent exhibitions include Ruin/Rien at Arcadia Missa in London and Dede, Eberhard, Phantom at Kunstverein Braunschweig near Berlin.