4 Columns

4 Columns

A supermoon rises over Queens on April 7, 2020, as viewed from the managing editor’s kitchen window.

4Columns returns with a new issue on September 4. In this week’s summer missive, we acknowledge the July 20 anniversary of the moon landing with a round-up of reviews culled from the archive that reckon

with outer space.

• • •

Last July, during a summer that now seems to belong to an alien reality, American media celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landing on the moon. This year marks a less conspicuous anniversary: that of the making of Small Talk at 125th Street and Lenox, Gil Scott-Heron’s debut album, recorded in the hottest months of 1970, at a midtown NYC studio in front of about twenty of his friends and family members. The ninth track on the album is the nearly two-minute “Whitey on the Moon”:

I can’t pay no doctor bill.

(but Whitey’s on the moon)

Ten years from now I'll be payin’ still.

(while Whitey’s on the moon)

Scott-Heron said his spoken-word piece was inspired by Black Panther information minister Eldridge Cleaver, who, appearing at a news conference in Algiers in the midst of his self-imposed exile from the US, had slammed Apollo 11 as a “circus to distract people’s minds” from aching, iniquitous Earth-bound troubles.

The message of “Whitey on the Moon” only seems to have gathered strength fifty years later, now that a demented president has bewilderingly established a new branch of the military called the “Space Force” and megalomaniac billionaires are in a race to colonize Mars. For these powerful figures, such unfathomably expensive ventures apparently eclipse solving tellurian problems like hundreds of thousands dying across the world in a pandemic that disproportionately harms people of color, soaring unemployment and economic inequality, and the mounting, scorching fury of climate change. Perhaps thanks to such delusional galactic ambitions, stories of outer space have once again come to the fore of cultural consciousness in the past few years, and 4Columns has published reviews of a constellation of books, films, and exhibitions in which the sublime expanse of the cosmos becomes the setting for grappling with ideas of vainglorious national identity, toxic masculinity, social injustice, and rapacious colonial greed—reviews in which Scott-Heron’s song is sometimes explicitly present, and for which the song always serves as an apt soundtrack.

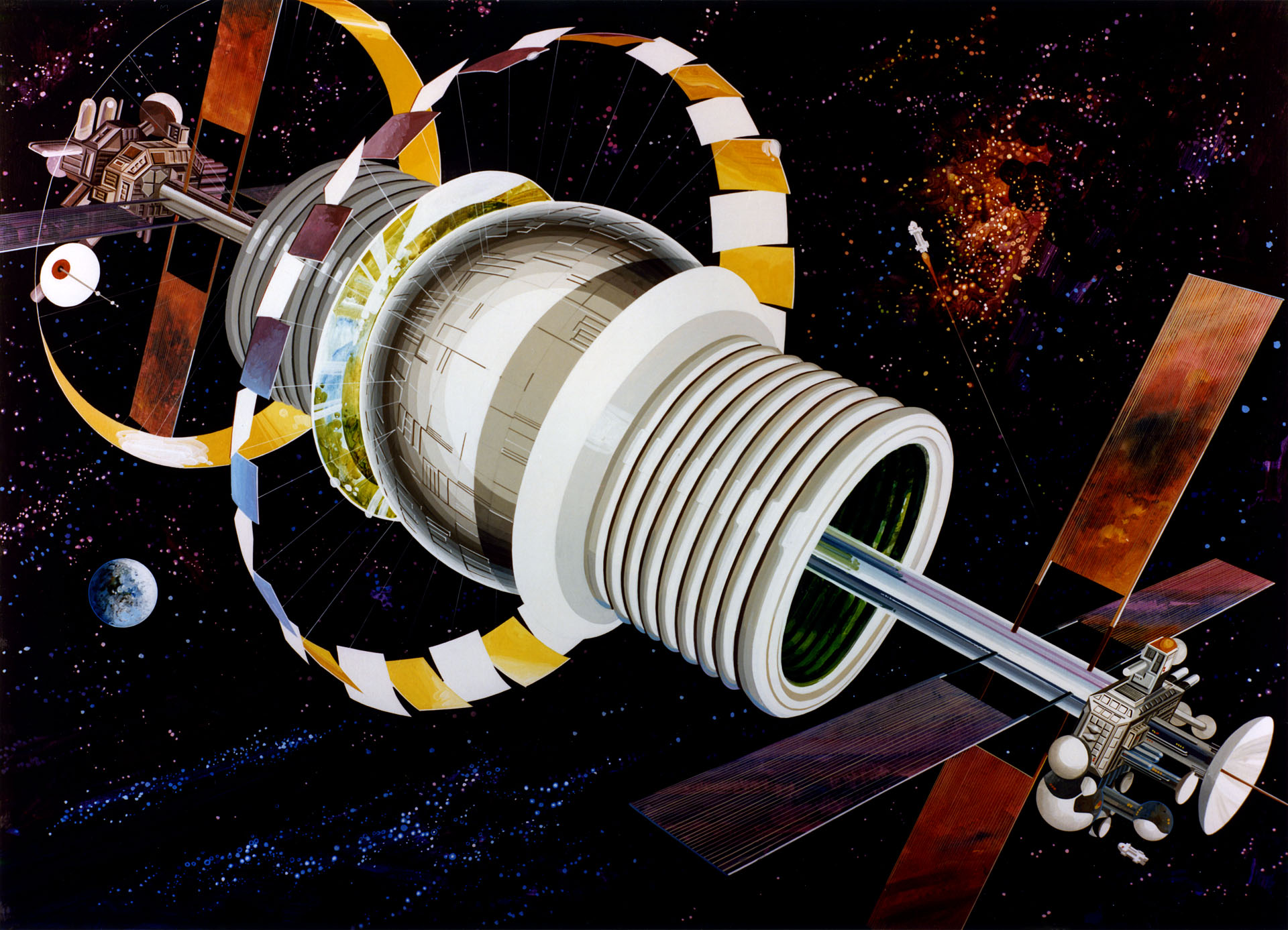

Rick Guidice, exterior view of Bernal Sphere, a point design with a spherical living area. Population: 10,000. Image courtesy NASA Ames Research Center.

Space Settlements, by Fred Scharmen

Reviewed by Noah Chasin

Fred Scharmen’s Space Settlements, published last July, examines NASA’s 1975 studies for building vessels among the stars that could house millions of people (studies that have served as research materials for Elon Musk’s more recent plans to populate Mars). Noah Chasin, in his review of Scharmen’s book, appreciated the scholar’s valiant effort to provide a theoretically and historically inflected take on his subject; but Chasin resisted any romantic or utopian notions about astronomical living: “The reason I remain unconvinced of the value of space travel . . . is that the effort operates as a metaphorical throwing up of one’s hands with regard to the problems that exist in and among the Earth’s citizens, landscapes, and environments. We cannot exhaust our planet’s resources and then start fresh somewhere else. Planned obsolescence is not a compelling strategy when contemplating the galaxy.”

Ryan Gosling as Neil Armstrong in First Man. Photo: Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures. © 2018 Universal Studios and Storyteller Distribution Co. LLC.

First Man, directed by Damien Chazelle

Reviewed by A. S. Hamrah

Back in 2018, prickly conservatives were outraged that Damien Chazelle’s Neil Armstrong biopic First Man didn’t adequately glorify the American flag subjugating the lunar surface—and indeed, that is a major point of the film, A. S. Hamrah argued in his review. It’s “as if the film is asking, ‘What was this United States of America, that it somehow put a man on the moon?’ A brief montage of homegrown resistance to NASA presents high-minded sci-fi novelist Kurt Vonnegut in an archival clip musing that perhaps space exploration is a waste of resources. Soul singer Leon Bridges shows up as Gil Scott-Heron at a rally delivering his proto-rap ‘Whitey on the Moon’ to protestors . . . Whitey, it could be said, is the star of this movie . . . First Man’s grimness, I think, is the product of uncertainty about what America means today and who has a place in it.”

Brad Pitt as Roy McBride in Ad Astra. Photo: Francois Duhamel. © Twentieth Century Fox.

Ad Astra, directed by James Gray

Reviewed by Melissa Anderson

If First Man presented the story of a tight-lipped Strong White Man who, in the good American way, is purely dedicated to his job, another entry in the recent cinematic “zero-gravity craze” (in the words of 4Columns film editor Melissa Anderson), James Gray’s Ad Astra, is also a tale of a White Man of Few Words. But here, that supernova of a star Brad Pitt plays not a determined American hero, but a sad man wandering through space in search of his father; Pitt’s astronaut, unlike Armstrong, is prone to corny voiceovers and conspicuous weeping. You see, Anderson writes, the film “is a galactic fable devoted to dismantling certain myths: about the folly of ambition, about sclerotic codes of masculinity.”

Robert Pattinson as Monte in High Life. © 2018 Alcatraz Films / Wild Bunch / Arte France Cinema / Pandora Produktion.

High Life, directed by Claire Denis

Reviewed by Melissa Anderson

Claire Denis’s recent High Life had perhaps even grander aspirations of completely exploding conventional ideas of gender roles and normative sexual desires. The sometimes-absurd sci-fi outer-space epic, also reviewed by Melissa Anderson, is also less white and male and American than the films mentioned above. In this story of death-row prisoners sent to space “as guinea pigs on a mission to harness the energy of black holes,” Anderson writes, “the supporting cast includes performers of different races, genders, nationalities, levels of fame, and acting abilities; consistently excellent is André Benjamin, formerly one half of the buoyant hip-hop duo Outkast.” Benjamin plays a pensive man named Tcherny, which, it must be problematically noted, is the Russian word for “black”—the character is named for his race, by a Russian space guard.

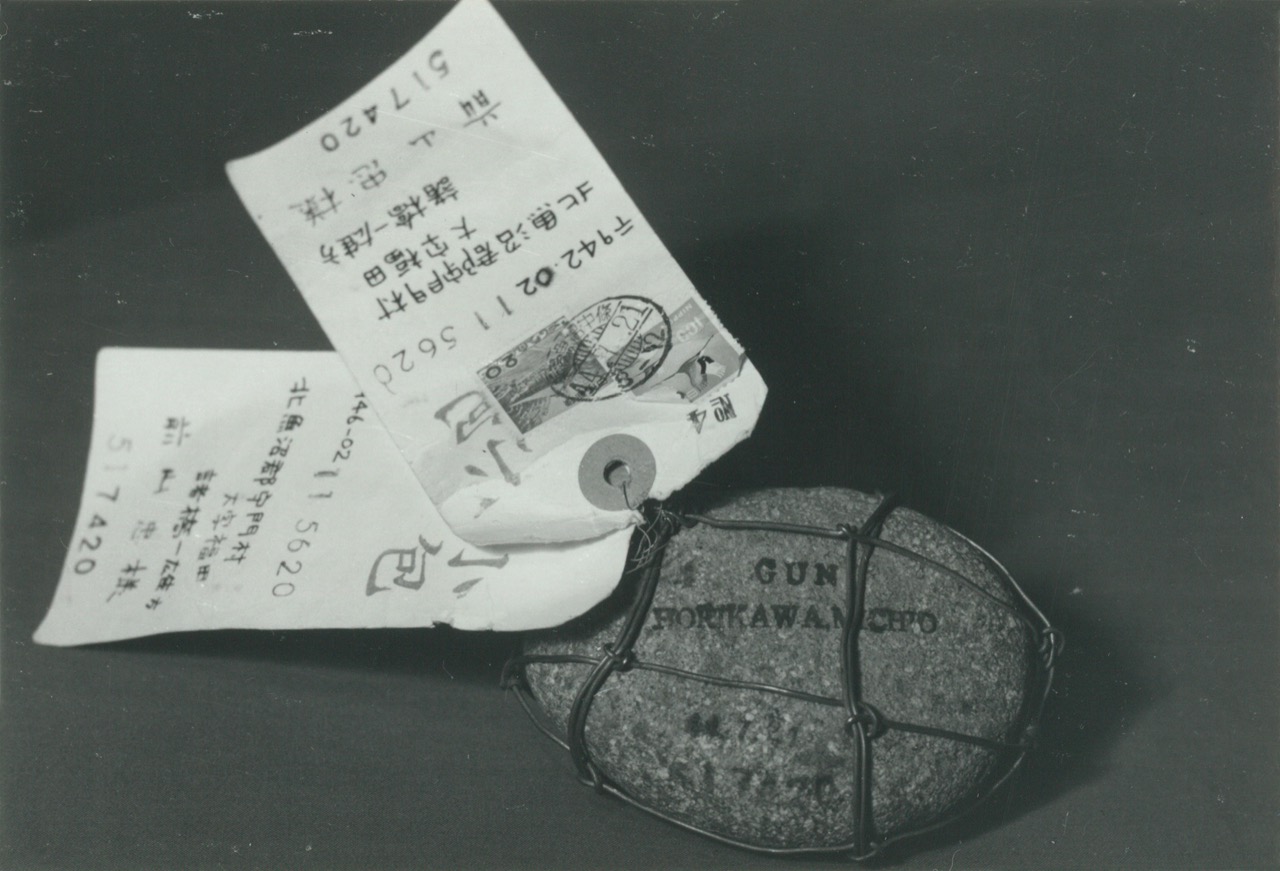

Horikawa Michio, Shinano River Plan 11, 1969. Image courtesy Misa Shin Gallery.

Horikawa Michio, Shinano River Plan

Reviewed by Alex Kitnick

Of High Life, Claire Denis said in a 2019 interview that “it could have been a Russian-language film . . . in space today you either speak Russian or English.” The US and Russia might be the great giants of the space industry, but artists from around the world have responded to their celestial missions. In Japan, Horikawa Michio led his seventh-grade students down the dry banks of the Shinano River while playing news coverage of the Apollo 11 landing on a portable radio and asked them to gather stones, like the astronauts collected moon rocks, explained Alex Kitnick in his deep dive into Horikawa’s Shinano River Plan (Kitnick’s essay also name-checks Scott-Heron’s “Whitey on the Moon.”) Horikawa “wasn’t convinced that wonder resided solely among the stars,” Kitnick writes. “The artist found earthly stones just as fascinating, or mundane, as their moonish counterparts. . . . Horikawa’s stones protest, too: he later shipped examples to Prime Minister Sato Eisaku and President Richard Nixon to demonstrate his opposition to the war in Vietnam.”

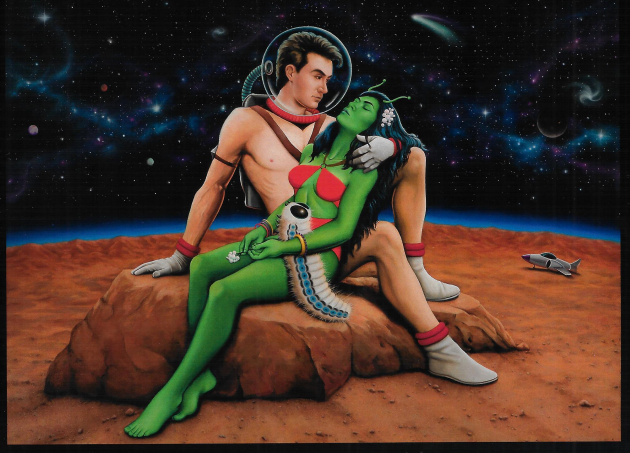

Laura Molina, Amor Alien, 2004. Oil paint, fluorescent enamel, metallic powder, 35 × 47 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Mundos Alternos, curated by Robb Hernández, Tyler Stallings,

and Joanna Szupinska-Myers

Reviewed by Ania Szremski

And from Horikawa’s cerebral mail art, we end up floating among the interstellar fantasies wrought by contemporary Latinx artists, on view last summer in an exhibition at the Queens Museum, Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas. The collected artworks used “that pulpy genre as fuel for jet packing to planes of experience estranged from accepted reality,” and proposed not conquering space, but fomenting revolution, managing editor Ania Szremski wrote in her review. “Early science fiction works in Europe and North America, steeped in colonial fantasies of conquering alterity, might be read as examples of what philosopher Bolívar Echeverría called la blanquitud, or ‘whiteyness’: a mode determined not only by ethnic features, but by a self-repressive Protestant ethic and ‘surplusvalue-productivitistic’ mentality that serves capitalist expansion. In this exhibition, artists counter that grasping ‘whiteyness’ with decidedly impractical folly.”