David Cote

David Cote

Extremely loud and incredibly verbose: a new play from Robert Icke forgoes the subtleties of showing for too much telling.

Juliet Stevenson as Ruth Wolff and Juliet Garricks as Charlie in The Doctor. Courtesy Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory.

The Doctor, written and directed by Robert Icke, adapted from Professor Bernhardi, by Arthur Schnitzler, Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue, New York City, through August 19, 2023

• • •

A priest and a physician walk into a bar. After the first round, the priest says, “Jesus turned water into wine, but no bishop or pope can explain how. Faith.” After the second round, the physician replies, “Jesus drank the wine and later turned it back into water. Urology.” Not a knee-slapper, but that’s my takeaway from writer-director Robert Icke’s The Doctor, a play that pits science against religion in the age of internet shaming. Although we certainly need more rational, humanist dramas to deepen the public discourse, this London import settles on being a histrionic and overwritten indictment of Our Cultural Moment: technology and the politics of outrage flattening human messiness while driving us into narrowing tranches of identity.

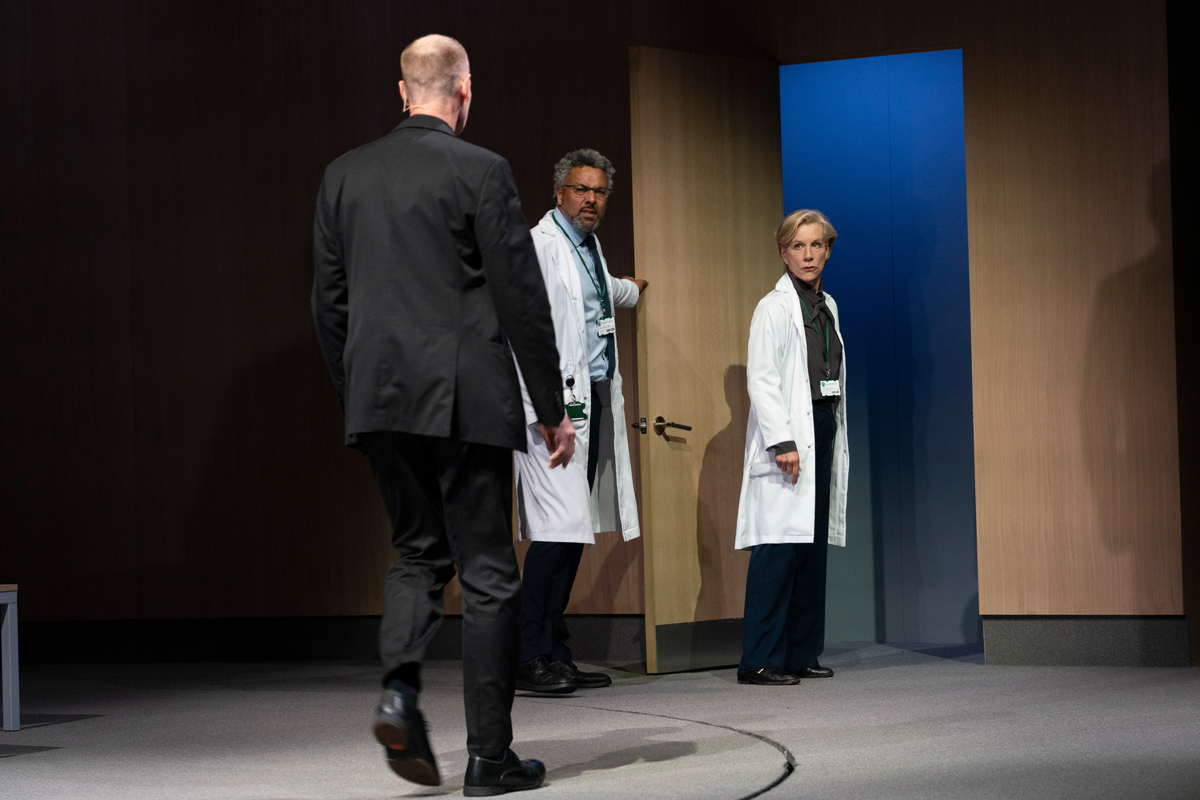

John Mackay as Father, Christopher Osikanlu Colquhoun as Copley, and Juliet Stevenson as Ruth Wolff in The Doctor. Courtesy Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory.

A priest and a physician also walk into this play. They clash outside a hospital room where a fourteen-year-old girl is dying of sepsis after a botched home abortion. A bit of argy-bargy ensues over who gets to ease the patient into impending death. The cleric (Roman Catholic) wants to give last rites; the clinician (Jewish) angrily prescribes antibiotics. This tête-à-tête is the principal bit of IP that Icke lifts from Arthur Schnitzler’s 1912 “comedy” Professor Bernhardi, including a dash of violence crucial to the story: the doctor will be accused of assaulting the priest. In Schnitzler’s version it’s clear the doctor is innocent; in Icke’s, stylized blocking and lights obscure what actually happens. Otherwise, The Doctor is a top-to-bottom update, now enjoying a pricey run at the monumental Park Avenue Armory, after opening in 2019 at London’s Almeida Theatre to critical raptures and then moving to Australia’s Adelaide Festival in 2020.

Over the past eight years, Icke, thirty-six, has risen in English and European theater circles with an almost Wellesian velocity. While associate director at the Almeida, he staged another “very freely” adapted classic in 2015: Aeschylus’s Oresteia, which draped corporate couture and live-video feeds over the tragic trilogy in a manner that, if not original, was at least shamelessly bold (it came to the Armory last summer). Clearly weaned on Regietheater conventions such as business suits, Brutalist scenery, abrasive lights, and incongruous pop songs, the auteur fuses the English genius for blunt, cutting lyricism (Pinter, Churchill) with ascetic, minimalist design. Icke is also astonishingly productive, refurbishing Ibsen, Chekhov, Schiller, and now the Viennese doctor-writer most famous for his erotic picaresque Reigen (aka La Ronde).

Easily the most obscure of Icke’s Western Civ all-stars, Schnitzler (1862–1931) trained as a nose-and-throat specialist, following in the otolaryngological footsteps of his father, before shucking the white coat and creating a body of well-received novels, stories, and plays, most often about adultery—sex without love—and the mental agony it produced. (His 1926 Traumnovelle furnished Stanley Kubrick with the raw material for Eyes Wide Shut.) By contrast, Professor Bernhardi—in its original five-act form and Icke’s two-part rewrite—is Schnitzler in a chastity belt. Any carnality has occurred offstage, resulting in a Catholic teen illegally terminating her pregnancy (in the update, by buying abortion drugs online). Schnitzler’s focus this time around was not bed-hopping among the bourgeoisie but rising anti-Semitism in Vienna circa 1900.

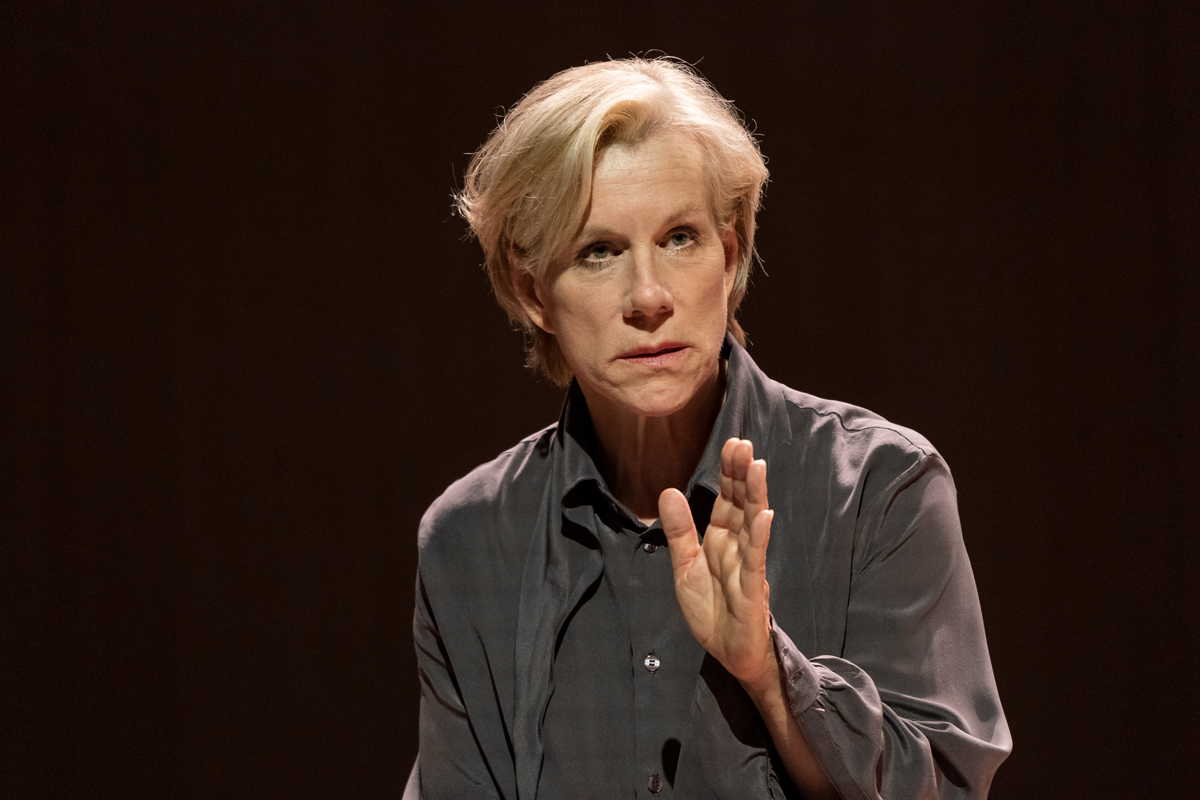

Juliet Stevenson as Ruth Wolff in The Doctor. Courtesy Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory.

In Icke’s gender-flipped makeover, the formidable Juliet Stevenson plays Dr. Ruth Wolff, the hard-charging director of the Elizabeth Institute, a private clinic researching a cure for Alzheimer’s. Wolff has taken on the girl’s case and fiercely defends her right to die in peace versus panicking at the sight of a priest entering her room. Wolff is Jewish, but staunchly secular; “I don’t go in for groups,” she snaps. She believes absolutely in science and fact and scoffs equally at religion and social media. When an internet petition demanding Wolff apologize to the offended priest (John Mackay) gains upward of fifty thousand signatures, some of Wolff’s colleagues (the Catholic ones) turn on her, pointing out that Jewish specialists are disproportionately represented at the institute, and perhaps doctors of faith should be assigned to like-minded patients. One of her defenders, another Jewish doctor, Copley, vehemently deplores such fashionable identity politicking. “You cannot just dump people into piles,” he fumes, insisting on every person’s “technicolor, thousandfold complexity.”

The cast of The Doctor. Courtesy Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory.

After much protracted and shouty soapboxing in the conference room (surely patients offstage are weakly jabbing their call buttons), the ninety-minute, often-tedious first act gives way to the imperious Wolff’s inevitable downfall, public humiliation, and slow crawl back to painful, flawed humanity. We learn the reason why she spends most of the play roaring orders and bulldozing everyone: grief, the full toll of which is only reckoned at the end.

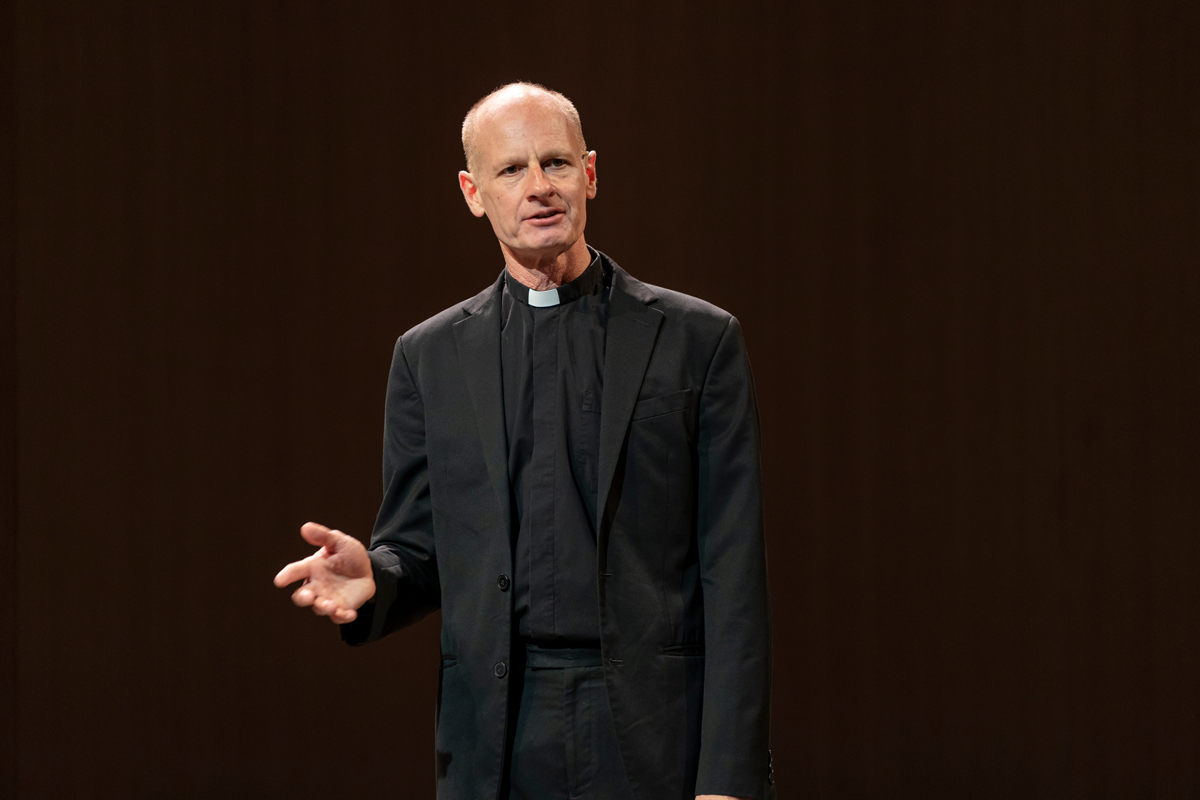

Which, at nearly three hours in, is far too long a wait. Many darlings could be killed in Icke’s baggy, repetitive script (the enfant terrible needs an éditeur superbe). There is fine, wistful dialogue in the final scene, and a handful of Twitter-ready zingers about identity politics and the science-versus-faith argument. But a superfluous TV “debate show” in the second act becomes a protracted, tendentious grilling of Wolff by experts who represent Jewish, Black, and pro-life camps—topped off by a young woman who lectures Wolff on the meaning of being “woke” shortly before blaming her for “hundreds of years of oppression and its legacies in the world we live in now.” Wolff, you see, called the priest “uppity” when she denied him access to the dying girl. The priest is Black. From an audience perspective, you wouldn’t know, since Icke uses a white actor.

John Mackay as Father in The Doctor. Courtesy Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory.

That brings us to the director’s big staging concept: casting actors against race and gender in roles inflected by those very qualities. I suppose the goal is to shock viewers, make us aware of our own assumptions, generate cognitive dissonance. After the device’s novelty wears off, though, you’re left with the plain fact that these characters are thin and one-note, never mind their blurred demographics.

Juliet Stevenson as Ruth Wolff and Matilda Tucker as Sami in The Doctor. Courtesy Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory.

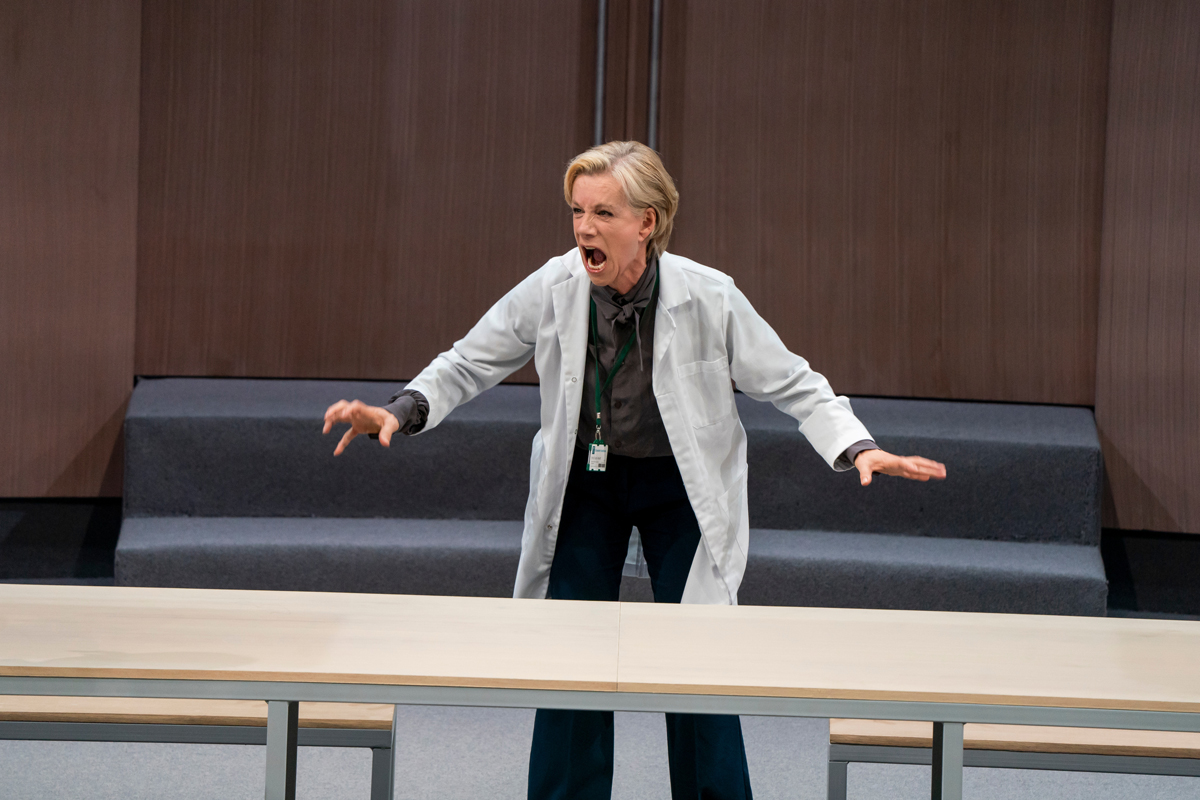

It’s hard to invest in any relationship in The Doctor. Everyone’s either too hot or too cold: arguing or aloof. Wolff has weak rapport with the socially awkward trans teen Sami (Matilda Tucker) who hangs around her house like a surrogate daughter, so their screamy breakup has little impact. Juliet Garricks slouches through scenes as the rueful Charlie, the gender-ambiguous ghost of Wolff’s dead lover. We barely learn anything about the personal lives of any of Wolff’s fellow health workers. Stevenson, a tireless, technically splendid dynamo, emotes with indignant urgency, an actor howling into the void where her character should be. She bellows, she snarls, she pounces, she fully embodies Ruth’s surname. The cumulative effect of all this strenuous, sub-Shavian oratory and posturing is, first, giggles, and then the realization that Wolff is unhinged and absurdly unprofessional. When she takes a patient’s blood pressure, she must bruise the bicep.

Juliet Stevenson as Ruth Wolff in The Doctor. Courtesy Stephanie Berger Photography / Park Avenue Armory.

Rather than building dramatic tautness or textured characters, Icke goads his cast into overacting or arranges them in stark, expressionist tableaux. After resigning her post, Wolff slowly peels off her lab coat, a spotlight blazing through it as if she were flaying her own skin. At the height of her existential breakdown, she keens and runs laps around Hildegard Bechtler’s curved wooden wall under Natasha Chivers’s slashes of light as accompanist Hannah Ledwidge pounds the drums in a perch above. Icke writes like someone who never heard the advice “show, don’t tell.” There are so many flavors of telling on this menu: hectoring, lecturing, haranguing. In that way, Icke deviates very little from Schnitzler’s verbose, rather inert issue play. When he pauses the incessant discourse to toss out a bit of eye candy, it’s like slapping a Band-Aid on a wound that won’t close.

David Cote is a theater critic, playwright, and librettist based in Manhattan. He reviews theater for Observer. His work has been produced in New York, Cincinnati, Chicago, and London.