Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Who bore it better? A new show at the Met presents the dueling agendas of the two modernist painters.

Manet/Degas, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Manet/Degas, cocurated by Stephan Wolohojian and Ashley Dunn in collaboration with Laurence des Cars, Isolde Pludermacher, and Stéphane Guégan, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through January 7, 2024

• • •

Art history loves its rivalries: Leonardo and Michelangelo, Ingres and Delacroix, Gauguin and Van Gogh, Matisse and Picasso, Pollock and de Kooning. And then, there is the odd couple of the later nineteenth century, the frenemies whose contrasting styles and personalities have come to stand for the internal contradictions of French modernism in the moment of its emergence—Manet and Degas.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863–65. Oil on canvas, 51 3/8 × 75 3/16 inches. © RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt / Art Resource.

On the one hand, you have Édouard Manet, a man of the haute bourgeoisie who seemed to perfectly embody Charles Baudelaire’s definition of a “painter of modern life”—a flâneur who moved with ease around a recently renovated Paris, where wide boulevards and outdoor cafés encouraged a new scopic relationship to the city, one organized around the pleasures of class privilege. And on the other you have Edgar Degas, a man who stood in uneasy relationship to his impoverished, aristocratic lineage, who seemed to insist on his distance from the modern world precisely so he could train his gimlet eye on its foibles, becoming a—perhaps the—painter of modern alienation.

Edgar Degas, Monsieur and Madame Édouard Manet, 1868–69. Oil on canvas, 25 9/16 × 27 15/16 inches. Courtesy Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art.

A blockbuster exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art pairing the two is simply titled Manet/Degas. But that minimalist slash mark does a lot of work here. Manet and Degas, Manet or Degas, Manet per Degas: across 160-odd paintings and works on paper, including Manet’s infamous painting of a courtesan, Olympia—displayed for the first time in the US—we are asked to see one through and against the other.

Manet/Degas, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen. Pictured, left: Édouard Manet, The Execution of Maximilian, ca. 1867–68. Oil on canvas.

What could have been a mere indulgence in the art historian’s favorite game of “compare and contrast”—or simply an opportunity to put a whole lot of eye candy on display (trust, there’s a lot of that, too)—is weirdly compelling, if only because it highlights the lopsidedness of the relationship. Degas depicted Manet, his elder by two years, multiple times over the course of their parallel careers—including once alongside his wife, Suzanne (Monsieur and Madame Édouard Manet, 1868–69), a composition so enraging to Manet that he lopped off one side of it, leaving Degas to remount it on raw canvas. After Manet’s death at age fifty-one, Degas threw himself into shoring up the former’s legacy, reconstructing the fragments of The Execution of Maximilian of circa 1867–68 (Manet’s most explicitly political painting, and one of his largest, which his stepson had cut up and sold for parts), supporting a fundraising campaign so that Olympia could enter the French national collections, and assembling a significant cache of his works.

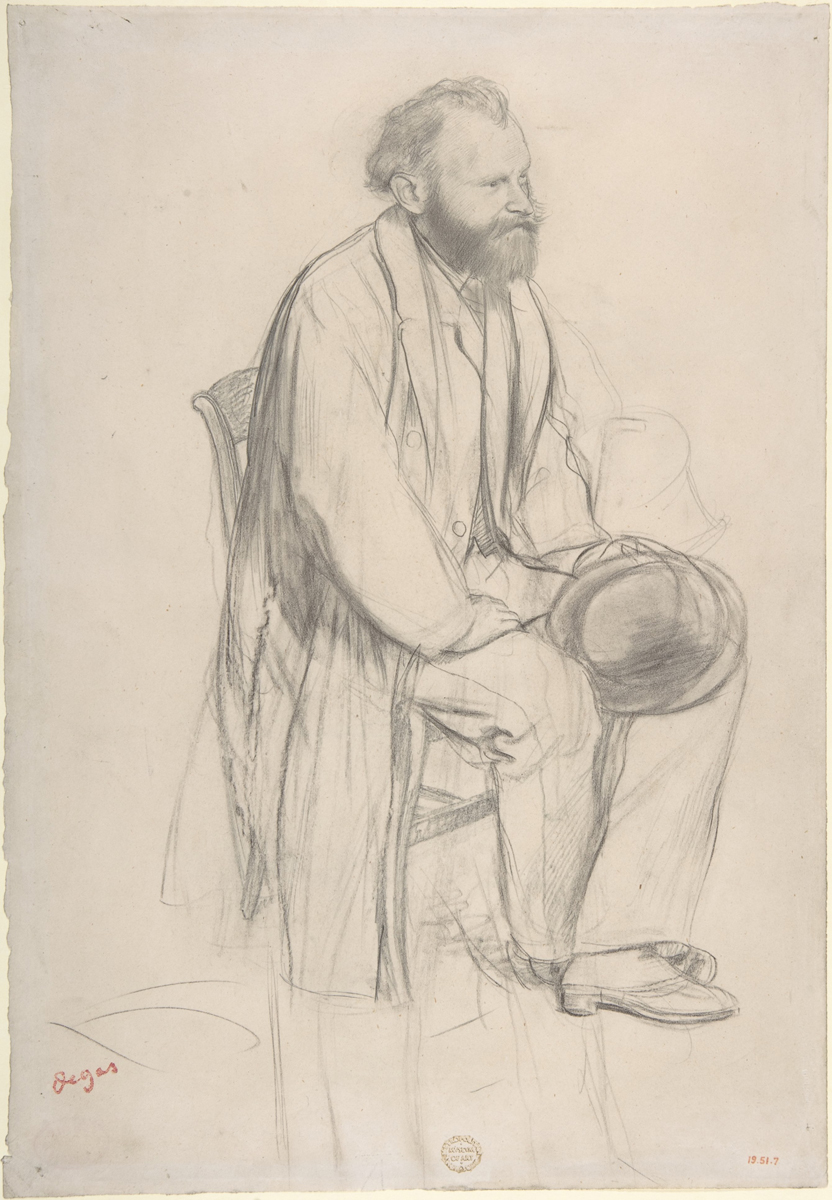

Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Seated, Holding His Hat, ca. 1868. Graphite and black chalk, 13 1/16 × 9 1/16 inches. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

It’s easy to see why Degas found his rival so compelling: in Degas’s portrayals, Manet embodies a kind of entitled ease, whether in his unselfconscious sprawl as he listens to Suzanne play the piano in Monsieur and Madame Édouard Manet or the effortless grace of his poses in Degas’s delicate pencil drawings and etchings, in which he even captures the elegance of Manet’s attire, the way his pants broke just there, as if all of Manet’s character could be summed up in the precision of his tailoring.

Manet, meanwhile, never portrayed Degas—not even once.

Manet/Degas, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen. Pictured, left to right: Édouard Manet, Study for Déjeuner sur l’herbe, ca. 1863–68; Fishing, ca. 1862–63.

Manet was the firebrand, the painter who was determined—following in the footsteps of Gustave Courbet, but with an urbane, blasé cool in lieu of the latter’s rustic, working-man’s bravado—to fuck things up from the moment he began showing publicly in Paris. Manet put naked women and clothed men together in the open air in Déjeuner sur l’herbe and allowed it to be shown at the Salon des Réfusés—imagine being so willing to have your work displayed among the rejects, available to the public’s scorn and derision. (That painting is represented here via an oil sketch from the mid-1860s, on loan from the Courtauld.) He was not afraid of pastiche, drawing freely from Titian (in Olympia), Raphael (in Déjeuner), Rubens (in Fishing, ca. 1862–63), Vélazquez (in innumerable single-figure compositions from the 1860s) to make images that were determinedly contemporary in both subject and style, including his use of a loose, flat brushstroke and refusal of conventional techniques of modeling form. Degas, on the other hand, hewed closely to academic technique, presenting enigmatic, classically rendered compositions, including Scene of War in the Middle Ages (ca. 1865), a historical painting without any clear connection to history, and Semiramis Building Babylon (1861), which emerged from his interest in Piero della Francesca, his mentor Ingres, and contemporary opera.

Manet/Degas, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen. Pictured, far left: Edgar Degas, Scene of War in the Middle Ages, ca. 1865. Oil on paper mounted on canvas.

But, as the show demonstrates, the binaries commonly mapped onto this artistic rivalry rarely hold for long: Manet, for all his rebelliousness, never stopped trying to show at the official French Salon, while Degas rejected such academic stamps of approval in favor of becoming a founding member of the first French avant-garde, the Impressionists. Manet was a painter, full stop, while Degas was fascinated with other mediums, including the fast-emerging technology of photography. A number of Degas’s own photographs are included in the exhibition, but it is in the artists’ respective treatments of horse racing that you can really see the impact of Degas’s curiosity and his understanding of the conceptual implications of looking through the camera’s lens. While Manet’s The Races in the Bois de Boulogne (1872) adopts an old-fashioned understanding of how horses run, with all legs stretched out at the same time as if they were cows jumping over the moon, Degas’s The False Start (ca. 1869–72), Racehorses Before the Stands (1866–68), and The Racecourse, Amateur Jockeys (1876–87) offer a far more convincing depiction of the horses’ skittish movements, as well as what could be called a “snapshot avant la lettre” composition, with its odd cropping and framing.

Édouard Manet, Plum Brandy, ca. 1877. Oil on canvas, 29 × 19 3/4 inches. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

The artists’ contrasting temperaments are fully apparent in the side-by-side hanging of Manet’s Plum Brandy (ca. 1877) and Degas’s In a Café (The Absinthe Drinker) (1875–76). The former shows a pretty working-class girl, with a dreamy, perhaps exhausted, look on her face, ensconced on a red banquette, leaning forward, a cigarette in one hand, the titular plum brandy (complete with whole plum!) in front of her. The marble table stretches so far into the foreground that we might be sitting just on the other side. She is a type, a fixture of the modern café, one of the many charming nobodies the flâneur might come across in a day; Manet allows us to step into his shoes and admire her surreptitiously—a pleasurable frisson. The Degas, by contrast, is all angles and barriers: a couple, posed for by painter Marcellin Desboutin and actress Ellen Andrée, seem trapped by the tables in front of them, distanced by the empty space in the painting’s mid-ground, squished in the corner with their drinks, not looking at us but, even more importantly, not looking at each other—caught in a depressing silence. Here, the café is not the place where you can gaze at a lovely face, but an alienating simulacrum of sociability.

Edgar Degas, In a Café (The Absinthe Drinker), 1875–76. Oil on canvas, 36 1/4 × 26 15/16 inches. © RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean / Art Resource.

I went to the show with an old grad-school pal. At the end of the tour, we jokingly asked each other, “So, who won?” I was surprised, given how long I had revered Manet for both his painterly gifts and the politics I saw buried within his work, that my answer this time was Degas. Everything that Degas seemed to most admire his opposite for—his assuredness, his confidence in both brushwork and attitude toward the world, his embodiment of cool—somehow rankles me today. Instead, I want Degas’s acerbic eye, his ability to see the darkness under what is being sold to us as pleasure, his sense of alienation from the world, of not living up to the past nor having the wherewithal to contend with the present. It feels more suited to our apocalyptic now.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns, and is author of Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts (Badlands Unlimited, 2018). She is currently working on a new book, Seven Pictures for a New World, and a volume of collected essays.