Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The Apsáalooke artist manipulates archival photos to explore her

tribe’s past.

Wendy Red Star, Apsáalooke Feminist #2, 2016. Photograph print on repositionable fabric. Image courtesy the artist and MASS MoCA.

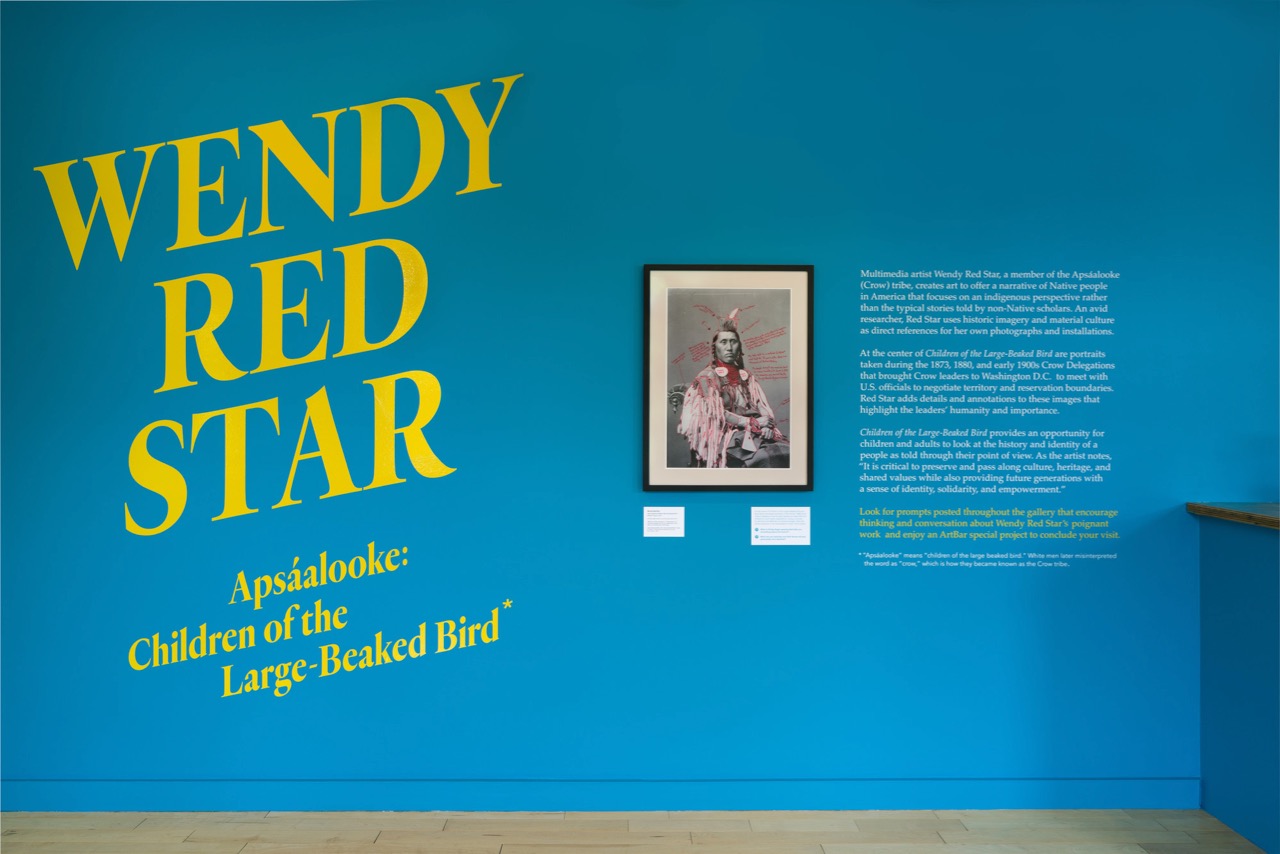

Wendy Red Star: Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird, Mass MOCA, North Adams, Massachusetts, through May 30, 2022

• • •

In his new book on Indigenous sound, Hungry Listening, Dylan Robinson notes that when the Stó:lō people in what is now called British Columbia first encountered white settlers in the mid-nineteenth century, they dubbed them “starving persons”—in part because they were literally starving, and in part because they were driven by a craving for gold. Likewise, in other Native languages, white people were understood to operate according to an extractive logic—a predilection to take from the land and its people what they needed to satisfy not simply their needs but their desires, to take without thought for consequence. Even as the new white settlers went about attempting to annihilate Native civilizations, people like the ethnographer and photographer Edward Curtis embarked upon a mission to mine their cultures, using the camera as his tool to record and consume, with the partial understanding of the white man, introducing stereotypes and flattening complex worldviews as much as documenting a living culture on the brink of extermination.

Wendy Red Star: Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and MASS MoCA. Photo: Kaelan Burkett.

Wendy Red Star’s work often aims to restore that which was looted in this form of knowing—to put back into images of the past some of what the camera, or more precisely the white gaze, had stripped away. Her current show at Mass MoCA is titled Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird—the name of her own tribe, which settlers imperfectly translated into English as “Crow”—and centers around archival photographs taken by the US Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Ethnography related to three tribal delegations to Washington DC in 1873, 1880, and the early 1900s. Red Star manipulates the images in various ways: blowing them up to wall size, creating life-sized and larger-than-life-sized cutouts of individual figures that stand around the gallery, and, perhaps most engagingly, annotating them using a red marker, allowing the figures to speak back to the settler’s rapacious gaze.

Wendy Red Star: Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and MASS MoCA. Photo: Kaelan Burkett.

Déaxitchish/Pretty Eagle (2014) hangs at the entrance to the show, which is installed in the museum’s Kidspace, the site of some of Mass MoCA’s most engaging exhibitions. It is an archival pigment print of a man who went to Washington in 1880, and who by 1886 was recognized as one of the leading chiefs of the Crow Tribe. Red Star uses her marker to outline the main contours of Pretty Eagle’s figure and to trace the details of the ermine fringe on his clothing, the lush beads around his neck, the rings on his fingers, the war axe in his hand, and so on. Her notations describe the significance of his attire and facts about his person—“Ermine on shirt, captured gun,” “6 ft,” “1885 Crow Census / Pretty Eagle, age 41 / wife: Pretty Shield / son: Holds His Enemy / daughters: Brings Good Things and Sings.” But they veer, too, toward the stomach-turning fate of so many Indigenous peoples in an era in which they were seen only as obstacles to North American settlers’ expansionism and treated as such. Here, the voice shifts from the neutral, “objective” tone of the researcher to a first-person address: “My remains, along with sixty other tribal members were stolen from their burial sites . . . My body sold to a collector for $500.00 and kept for 72 years at the American Museum of Natural History. My people brought my remains back to Crow Country on June 4, 1994 . . .” The offering of such details to this and several other images imbue a specificity and even agency to the portrait subjects that is deeply moving—these men are not types anymore, but people.

Wendy Red Star: Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and MASS MoCA. Photo: Kaelan Burkett.

In the next room, in addition to more annotated portraits, an enlarged group photo of the 1873 delegation appears on the back wall; Red Star was especially drawn to the image because it was the only one she found from that trip that included women—wives of the tribal leaders. In front of it, facing the entrance as if welcoming us into a ceremonial space, are cardboard cutouts of tribal leaders that took part in one of the later delegations; leaning against the wall are even larger blowups of others, a number of whom wear suits and ties and close-cropped hairstyles instead of braids and elaborately decorated buckskins. The simple arrangement functions to position us, the viewers, as their guests—now meeting on their terms.

Wendy Red Star: Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and MASS MoCA. Photo: Kaelan Burkett.

The third gallery of Kidspace is a mixed-use studio in which children and adult visitors are invited to do hands-on activities in relation to the artworks on display. Here, in vitrines and framed on the wall, is one of Red Star’s playful propositions about what it would be like to see the world through an Indigenous lens, and to value Native forms of knowledge. When a man named Medicine Crow went with the 1880 delegation to Washington, he made drawings of the non-native animals he saw at a circus: a lion, a red catfish, “a spotted mule” (zebra), an “elk with big back on him” (camel), and so on. (They were preserved by a clerk at the Bureau of Indian Affairs.) Working with a toy manufacturer, Red Star has created plushy stuffed animals (all dated 2020) based on some of the drawings, which are at the same time filled with innocent wonder and very precise in their observation.

Red Star’s research into the past is inextricably tied to the survival of her culture in the present and future. A sound-and-image piece consisting of the artist’s father speaking the names of various animals in his Apsáalooke language as slides of pictures made by young visitors in response to the descriptions translated into English appear on a small monitor is particularly charming. (What would a creature called “Scoots Along the Ground” look like to someone first hearing the term?) It is an important adjunct to Medicine Crow’s descriptive project almost a century and a half before, after years of US effort to extinguish Native languages by removing children from their families and putting them in residential schools so that they would not be able to learn their mother tongues and the histories their parents and elders would have otherwise communicated to them through spoken word and song.

Wendy Red Star, Indian Summer—Four Seasons, 2006. Photograph print on repositionable fabric. Image courtesy the artist and MASS MoCA.

In galleries dominated by black-and-white and sepia images punctuated by red markings, two photographic murals stand out for their technicolor glory: Indian Summer—Four Seasons (2006) and Apsáalooke Feminist #2 (2016). The first shows the artist, attired in Crow regalia, sitting in an ersatz mountain landscape—Astroturf, cutout deer, fake flowers, fake foliage, fake everything—in a way that evokes cheesy natural-history museum dioramas and 1950s Hollywood westerns. The second depicts Red Star and her young daughter, again dressed in elk-tooth dresses, sitting, chins cupped in hands, on a modern couch draped with what look to be mass-market blankets and throw pillows that nod to generic Plains Indian motifs. The background is a computer manipulation of a striped trading blanket. In both, the gentle humor of the contrast between the very vital figures of the artist and her daughter and the deadening stereotypes that surround them is a stark corrective to the manner in which Indigenous cultures are often treated in this country as a vestige of the past. Red Star’s work is, as much as anything, a history of our present.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, an upcoming retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a member of the advisory board of 4Columns. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.