Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

The octogenarian avant-garde composer takes up electric guitar.

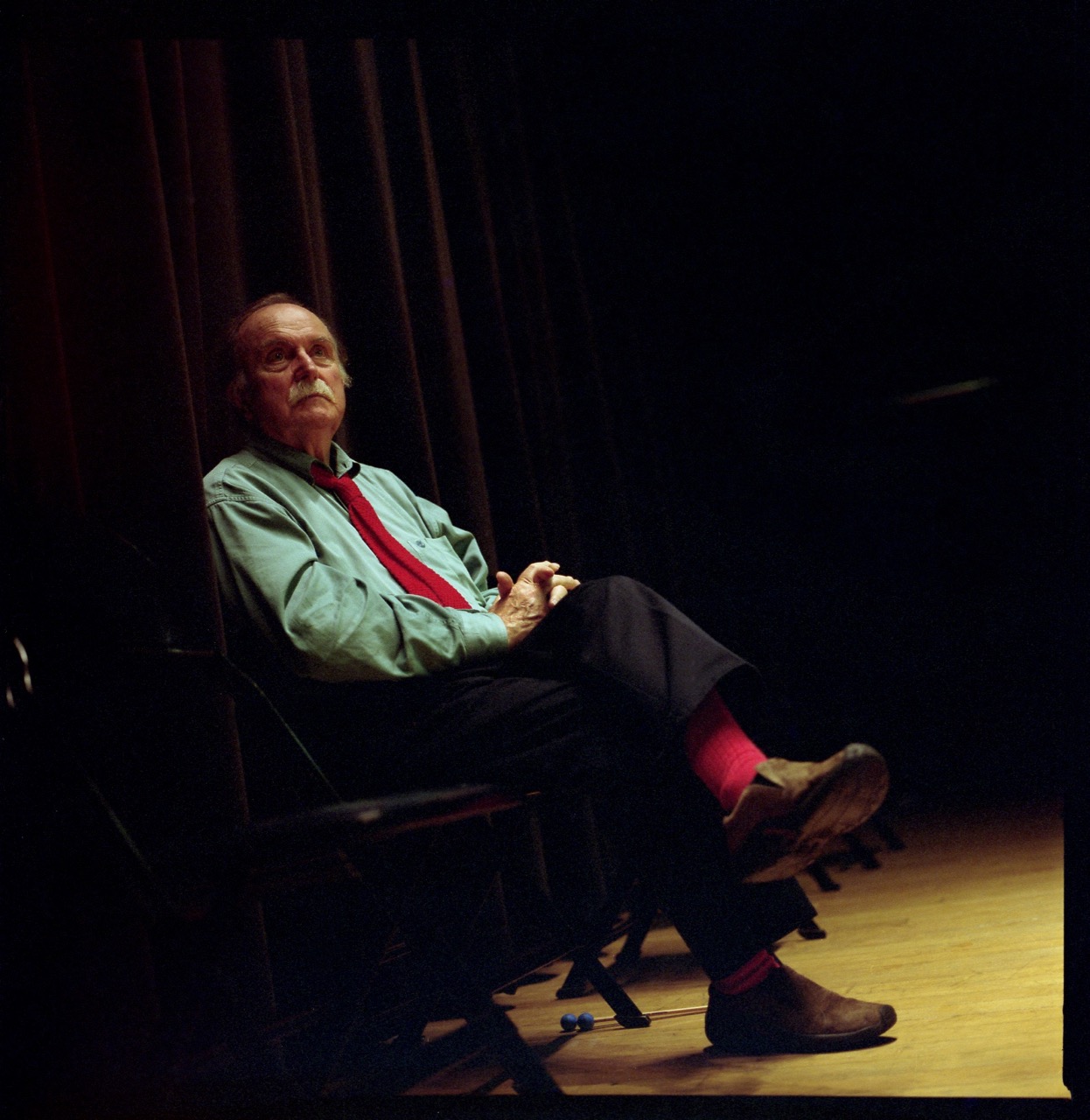

Alvin Lucier. Photo: Kris Serafin. Image courtesy Black Truffle.

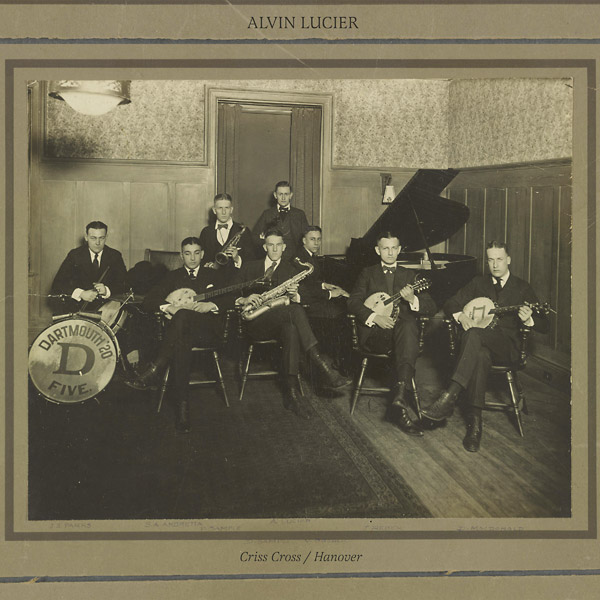

Alvin Lucier, Criss-Cross / Hanover, Black Truffle

• • •

It would be tempting to call the legendary Alvin Lucier a twentieth-century composer—he made his mark there, along with many of his late friends, including John Cage and David Tudor. But Lucier is now a twenty-first century composer, actively creating and performing new music at the age of eighty-six. At a recent Lucier concert at Issue Project Room in Brooklyn, much of the program was made over the past few years. (He also led a performance of his 1970 classic of repetition and resonance, I Am Sitting In A Room, prominently sporting a “Black Lives Matter” shirt with a look of quiet defiance in his eye.) Lucier’s immense body of work stretches back over sixty-six years, and his approach is still relentlessly forward-thinking. It is possible that no artist has investigated the materiality of sound as thoroughly as Lucier—and all sound artists have something to learn from him.

“Scientific experiments have often given me ideas for pieces; sometimes I do little more than frame them in an artistic context,” Lucier wrote in Leonardo Music Journal in 1998. But his works are not simply technical demonstrations of acoustics. “Lucier has often been described as a ‘phenomenological composer,’ but to do so strips his music of much of its richness,” argued the composer Nicolas Collins in the liner notes for the 1990 Lovely Music release of I Am Sitting In A Room. He notes that while Lucier has a strong interest in acoustic phenomena, his pieces can also be about “discovery and transformation” (Chambers, from 1968), “social responsibility and survival” (Vespers, also from 1968), and in the case of I Am Sitting In A Room, its narrator.

The first surprising thing about Lucier’s latest album, Criss-Cross / Hanover, is the homespun, old-fashioned cover art; on the surface, it seems at odds with the music itself, and its often spare and minimal sonic qualities. The album cover is, in fact, a vintage photograph of Lucier’s own father on violin in 1918 with his band at Dartmouth College—a group of eight serious-looking men in sharply pressed suits, wielding banjos and other instruments, their sober expressions frozen in time. Lucier’s composition “Hanover” (2015), which comprises the second half of this new release, is inspired by that photograph—using much of the same instrumentation as his father’s band (including violin, saxophone, and piano), but swapping the banjos for electric guitars. The eighteen-minute-long piece sounds dissonant and alien; it is far richer in timbres than “Criss-Cross,” but feels austere just the same.

Oren Ambarchi, Alvin Lucier, and Stephen O’Malley. Photo: Judith Hamann. Image courtesy Black Truffle.

“Criss-Cross,” featuring the formidable talents of the guitarist Stephen O’Malley of the group Sunn O))) and the experimental musician Oren Ambarchi, is the star of this release. It is Lucier’s first-ever work for electric guitar—Lucier originally wrote it in 2013, specifically for O’Malley and Ambarchi—but it doesn’t sound like electric guitar at all, in any conventional sense. The mysterious hum created by it could be a cosmic synthesizer, or a UFO landing, or a refrigerator fan gone deeply awry. The piece requires intense concentration to perform: done correctly, it eventually generates sound waves that spin between the speakers. One guitarist plays through the left channel, the other through the right channel. They both play the same note, but slightly off each other: one musician slowly sweeps up from half a semitone below the note of B, while the other slowly sweeps down from half a semitone above. As they begin to intersect, one hears audible interference patterns, called “beating.” The guitarists keep sweeping up and down continuously for fourteen minutes—all while holding an EBow, a small electronic device that promotes vibrations, up to the B string—and gingerly moving a tuning peg ever so slightly, back and forth, on their guitars to move the note above and below B.

The magic happens when the beating gives way to powerfully palpable spinning sound waves—a disorienting effect. “Under certain acoustic conditions the sound waves may be heard to spin from speaker to speaker in the direction of the higher pitch to the lower,” Lucier explains in the score. Through all of this, the guitarists attempt to move at a constant speed—Lucier doesn’t exactly specify the duration of each sweep, but the two musicians begin to lock into each other’s movements, coming apart and coming together in a sort of dance.

“Criss-Cross” is difficult to perform—and difficult to capture properly in a studio. The recording of “Criss-Cross” here is top-notch, recorded and mixed by François Bonnet at the famed INA-GRM Studios in Paris, with the mix closely supervised by Lucier himself. The work also requires a major investment from the audience; listening to it demands your full attention. (A Japanese performance of “Criss-Cross,” viewable on YouTube, depicts several audience members losing patience, slowly leaving one by one during the performance.) There is no melody, no song structure, nothing to hang onto—except for the sound waves themselves.

But in this “research music,” we contend with sound at its most elemental. “In retrospect, it is surprising that so often, these composers used scientific, mathematical or acoustical testing procedures as structural methods,” Lucier wrote in 1998, describing work by several of his friends, including Cage, Gordon Mumma, and James Tenney—but also, of himself. “It is ironic that most of these pieces were intensely personal, particularly as far as the performances were concerned. The neutrality of these structures seemed only to place the performer, and therefore the listener, more firmly in the human situation in which most people found themselves in that burgeoning technological world.”

“Criss-Cross” has a potent, almost punishing intensity, even at a low volume. One guitarist friend was bored by it, asking me why Lucier chose to use live guitars, when he could have used synthesizers or computers to produce a similar effect. But after listening to “Criss-Cross” on repeat, I felt a sensation akin to when I first heard John Cage’s “Cartridge Music” (1960)—a sort of epiphany. Cage upended the turntable, liberating the cartridge from its task of conveying vibrations from record to amplifier—turning it into an instrument of its own. In a similar way, Lucier’s guitars weren’t guitars anymore, in any familiar or socially approved sense of the word, but something else, free of their earthly structure in wood and metal. All that was left was the sound.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.