Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

The sound that time forgot: remembering the experimental

musician and filmmaker.

Phill Niblock. Photo: Daniel Efram.

1933–2024

• • •

Twenty-three years ago, I bought Phill Niblock’s Touch Works: For Hurdy Gurdy and Voice at Other Music, a record store in Manhattan’s East Village. For the experimental-music heads who frequented the shop, the album was practically a Top 40 hit. I was transfixed; I couldn’t stop playing it. For the epic fifteen-minute opening track, “Hurdy Hurry,” Niblock layered hurdy-gurdy samples recorded by the musician Jim O’Rourke, distilling the old-fashioned instrument down to its woody essence. The rich timbres conjured potent memories of my childhood spent playing the harmonium. There were no conventional melodies or song structures in those shimmering, multidimensional drones, but they were heavy in emotional resonance.

Niblock, who passed away this month at the age of ninety, had been a central figure in experimental music, photography, and cinema since the 1960s. Born in 1933 in Indiana, in 1958 he relocated to New York City, where he became part of the fabric of the downtown scene. “I was a jazz fan, and that was part of the reason I moved to New York,” he told me when I interviewed him for frieze in 2016. “I didn’t come here for anything in particular.”

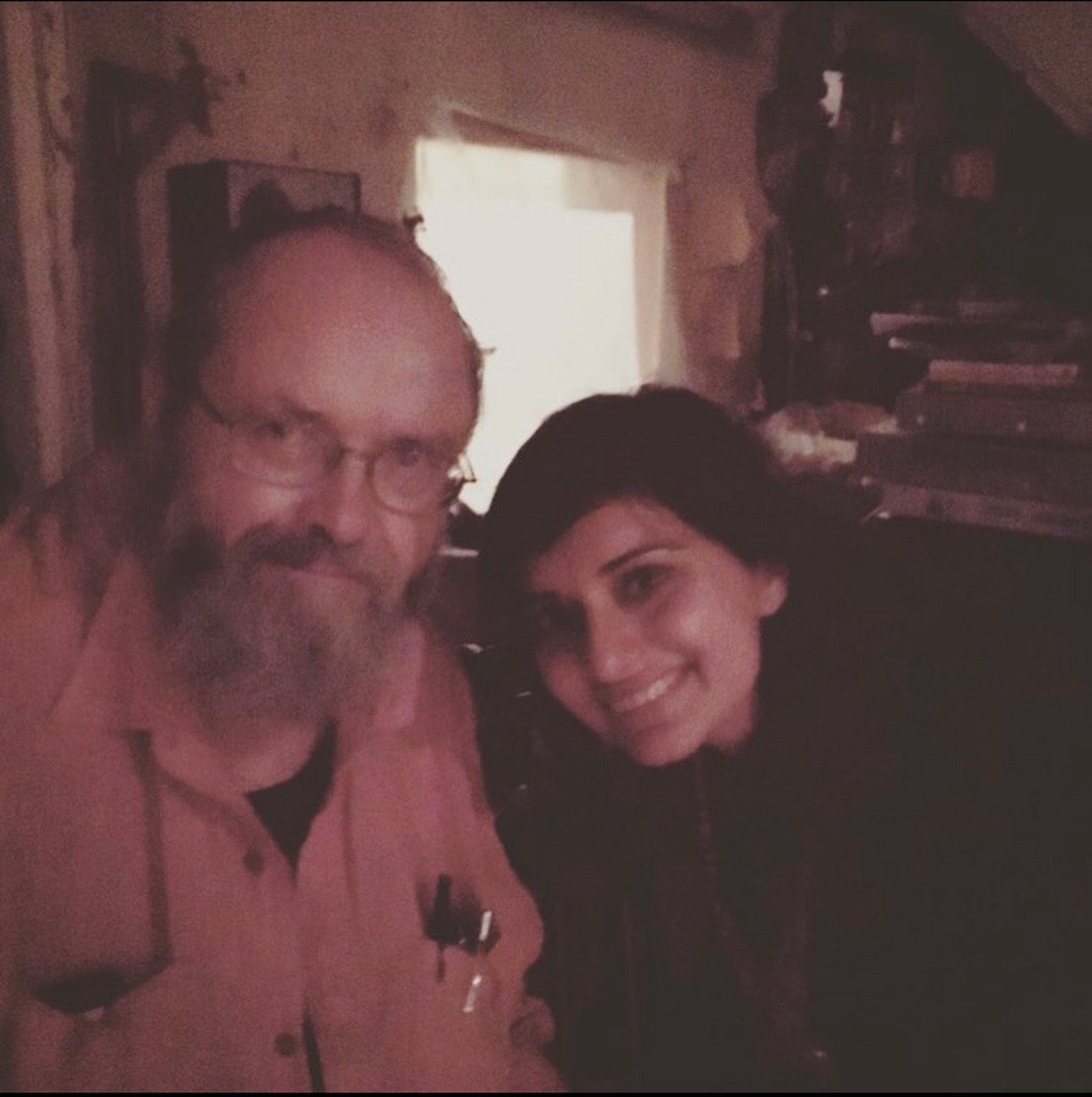

Phill Niblock and Geeta Dayal at Experimental Intermedia Foundation. Courtesy Geeta Dayal.

He learned how to use a camera and soon landed a gig photographing Duke Ellington and his band. He immersed himself in jazz and developed an interest in modern art. “I was extremely interested in Minimalism,” he said. “When I came to New York, I went to a lot of galleries and saw a lot of work. People like Barnett Newman or even Hans Hoffman were really something distinctive for me; I was really drawn to that.”

He became friends, and started making film, with the choreographer and intermedia artist Elaine Summers, “who was very involved with the Judson Dance Theatre, the Judson Church,” he said. “The first post-Cunningham dancers were working there.” Niblock made several short films during the 1960s, including The Magic Sun (1966), an energetic collage of close-ups of Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra paired with the group’s music. He also began tinkering with combining film projections with live performance, slides, and other elements.

Phill Niblock, on the fire escape of Experimental Intermedia Foundation’s loft on Centre Street. Photo: Katherine Liberovskaya.

But Niblock didn’t particularly align himself with the avant-garde filmmakers of the 1960s. “I was never really known as an experimental filmmaker because I was really interested in concrete, clear images,” he said. “I was interested in photographic-looking film.” A plainspoken guy with a beard who studied economics at Indiana University, he described himself to me as a “non-joiner.” He eschewed the glitzy scene surrounding Andy Warhol’s Factory and created his own instead. In 1968, he and Summers established the Experimental Intermedia Foundation in a cavernous loft on Centre Street in downtown Manhattan. It remains, to this day, a rare and crucial venue for performances of noncommercial creative work, where a concert costs $4.99. Its continued existence, after over fifty years, is a small miracle in the hyper-expensive landscape of New York City. “I’ve always wanted [Experimental Intermedia] to be very free and open,” he said. Niblock also used the structure to workshop and perform his own projects.

Niblock’s most enduring cinematic endeavor was The Movement of People Working, an expansive film, begun in 1973, that depicted the ordinary routines of laborers around the world, from Hong Kong to Peru, set to his own slow-moving soundtrack. He viewed the piece through the lens of dance. “I started to film people working as sort of dance movement, essentially,” he said. “So it didn’t have to do with what they were doing; it had to do with the way they moved in the frame. Very much dance film, not ethnographic or political in any way.”

He also collaborated with the composer and cellist Arthur Russell, maintaining a friendship up until Russell’s death from AIDS-related complications in 1992. An especially poignant project made together is the film Terrace of Unintelligibility, shot in Niblock’s loft in 1985. It is starkly personal in its extreme close-ups of Russell as he performs some of his most intimate songs, a departure from the relative anonymity and sweeping vastness of The Movement of People Working.

Phill Niblock. Photo: Daniel Efram.

Niblock’s musical output was wide in its scope, employing a range of collaborators and instruments from flute to didgeridoo to strings in albums including Four Full Flutes (1990), A Young Person’s Guide to Phill Niblock (1995), and Music for Cello (2018). Though his approaches and materials varied, his guiding principles stayed the same. “I’m interested in working with this cloud of sound,” he told me. “So that’s a primary thing. I build up to it in a piece fairly slowly, but then it becomes that sort of determined cloud for a very long time.”

“Time” is the operative word here—Niblock shaped not only sound but our concept of time itself. His long pieces subtly change and unfold without any conventional ideas of musical development. They challenge us to listen in new ways, to have patience for sound in all its infinite variations of tones, overtones, and microtones. “I’m very interested in this idea of extended time, and an ideal concert is one where people don’t know how long it was,” Niblock said. “They don’t have a sense of time passing.”

Phill Niblock. Photo: Daniel Efram.

Niblock seemed ageless, much like his fellow composer and sonic explorer Alvin Lucier, who passed away in 2021, also at the age of ninety. Like Lucier, Niblock maintained a vigorous schedule well into his eighties—touring in far-flung countries and making new pieces at a furious pace. His legacy today extends beyond his own significant body of work. He inspired generations of artists and musicians to push the limits of sound and film. But perhaps more importantly, in a frenetic, fast-paced world dominated by capitalism, his art invites us to slow down. It reminds us to trust in the creative process, to spend more time listening.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World (Bloomsbury, 2009), a book on Brian Eno, and is currently at work on a new book on music.