Mark Dery

Mark Dery

Hawthornian horror gets the postmodern treatment in Daniel Clowes’s latest graphic novel.

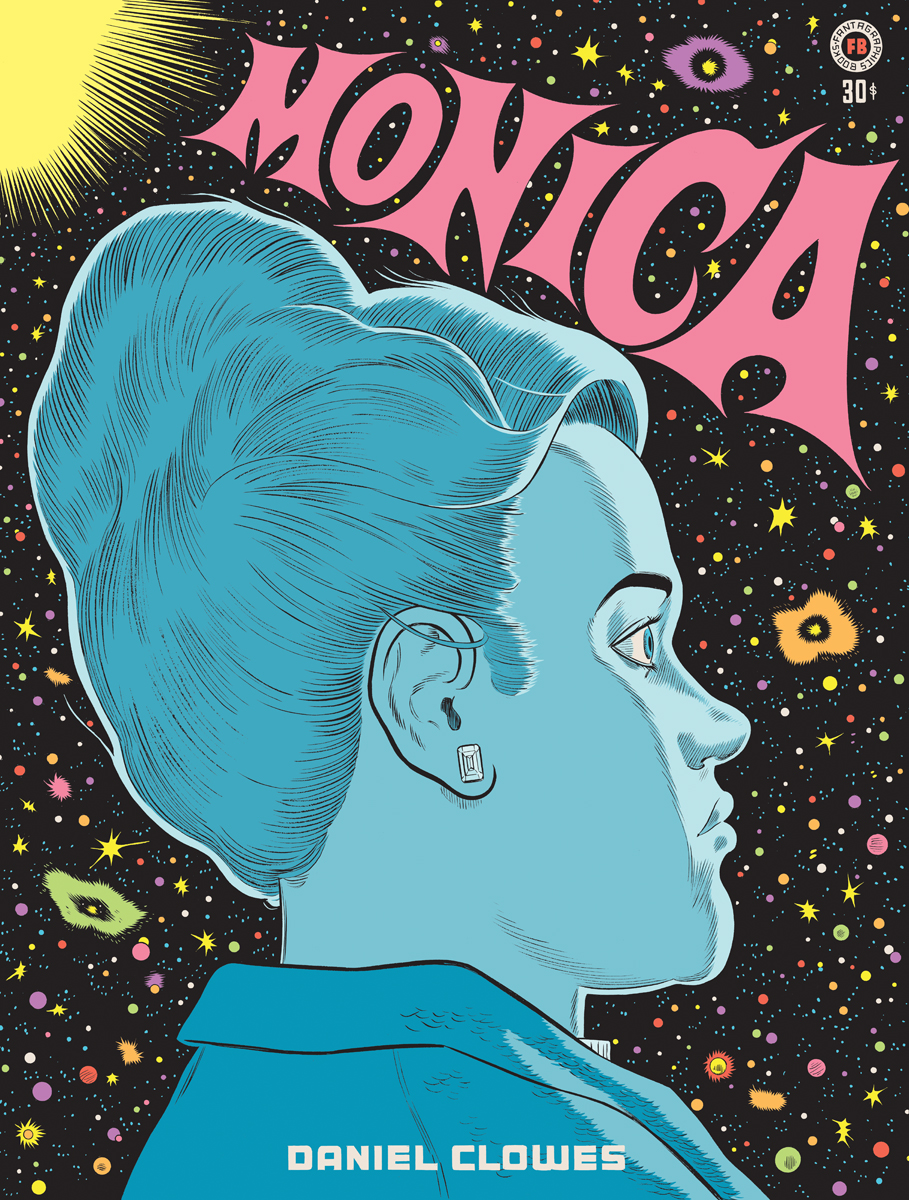

Monica, by Daniel Clowes, Fantagraphics Books, 106 pages, $30

• • •

In 2016, when his graphic novel Monica (out on October 3) was still fermenting in his unconscious, Daniel Clowes told Wired magazine, “This one . . . may be more of a gothic horror kind of thing.” “Along the lines of Edgar Allan Poe?” the interviewer wondered. “I’m thinking more Nathaniel Hawthorne,” said Clowes.

Few Clowes fans—if any—saw that coming. The Comic-Con demographic reveres him as a post-punk auteur whose mordantly funny anthology series Eightball played a key role, in the 1990s, in transforming the comic book, dismissed by mainstream tastemakers as malodorously geeky, into a serious art form. The mass audience that knows him from Terry Zwigoff’s movie adaptations of Eightball stories like Ghost World (2001) and Art School Confidential (2006) associates him with the post-’60s cynicism and deadpan irony that were Gen X’s birthright (even though the cartoonist, born in 1961, is a Boomer, strictly speaking). Trend-story shorthand: Catcher in the Rye plus Blue Velvet equals Clowes.

From Monica. Courtesy Fantagraphics.

In Monica, his trademark cynicism about the Lynchian depravity behind the salesman’s smarm and self-help platitudes of American life has shifted into a more pensive, philosophical key. Clowes is resolutely the atheist he always was, but Monica reveals his Gen-X cynicism as the zeitgeist-y side of a deeper disquiet. He’s “opposed to the idea of religion,” he told his friend the cartoonist Seth, but can’t escape the feeling that “somewhere, behind everything, is some unseen world that’s much more mysterious.”

In Hawthorne’s stories, that darkness behind daylit reality is the Puritan horror of original sin that shrivels the soul of the clergyman in “The Minister’s Black Veil,” who is tormented by the knowledge that every one of his parishioners is “loathsomely treasuring up the secret of his sin.” It poisons the mind of the devout “Young Goodman Brown,” who, having seen pious grandams and sober deacons worshipping the Devil at a witches’ sabbath, can never unsee that awful truth.

Clowes is the furthest thing from “dismal wretches” like Goodman Brown, but he’s haunted, as are his protagonists, by what Hawthorne calls “the moral gloom of the world.” As early as 1997, he mused, in an interview with the comics scholar Daniel K. Raeburn, “While I don’t accept organized religion, I still think it deals with questions that have to be dealt with. I think that’s sort of what I’m looking for in my comics.”

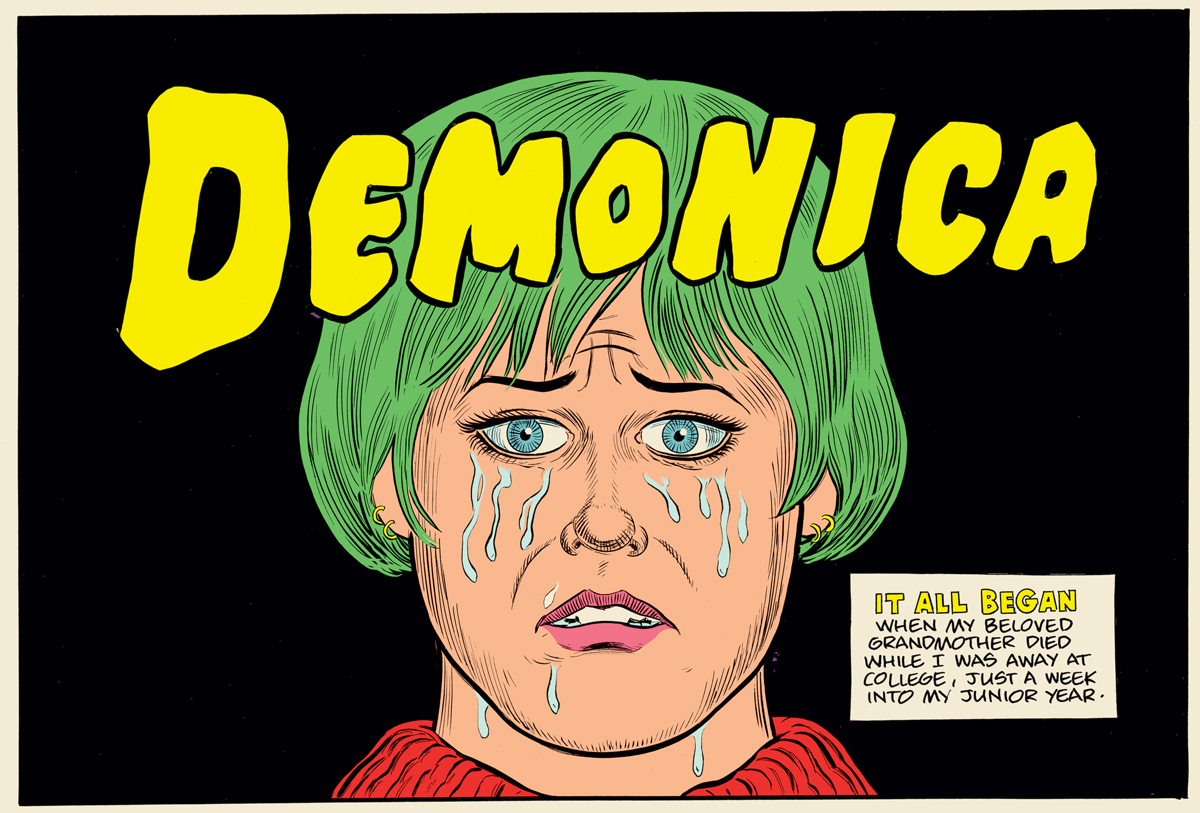

In Monica’s cover story, a mystery about a woman desperate to unriddle the miseries of her childhood, Clowes confronts—with his usual black-comedic wit—questions usually reserved for religion. He wrestles with the complications of life after death (what do you do when grandad reveals himself, from beyond the grave, as an anti-Semite?); unearths the historical roots of Gen-X angst and anomie, which for Clowes are the psychic scum left by the receding wave of the counterculture; ponders the perils (and seductions) of blind faith; and takes the full, painful measure of the persistence of memory that makes us prisoners of our pasts.

From Monica. Courtesy Fantagraphics.

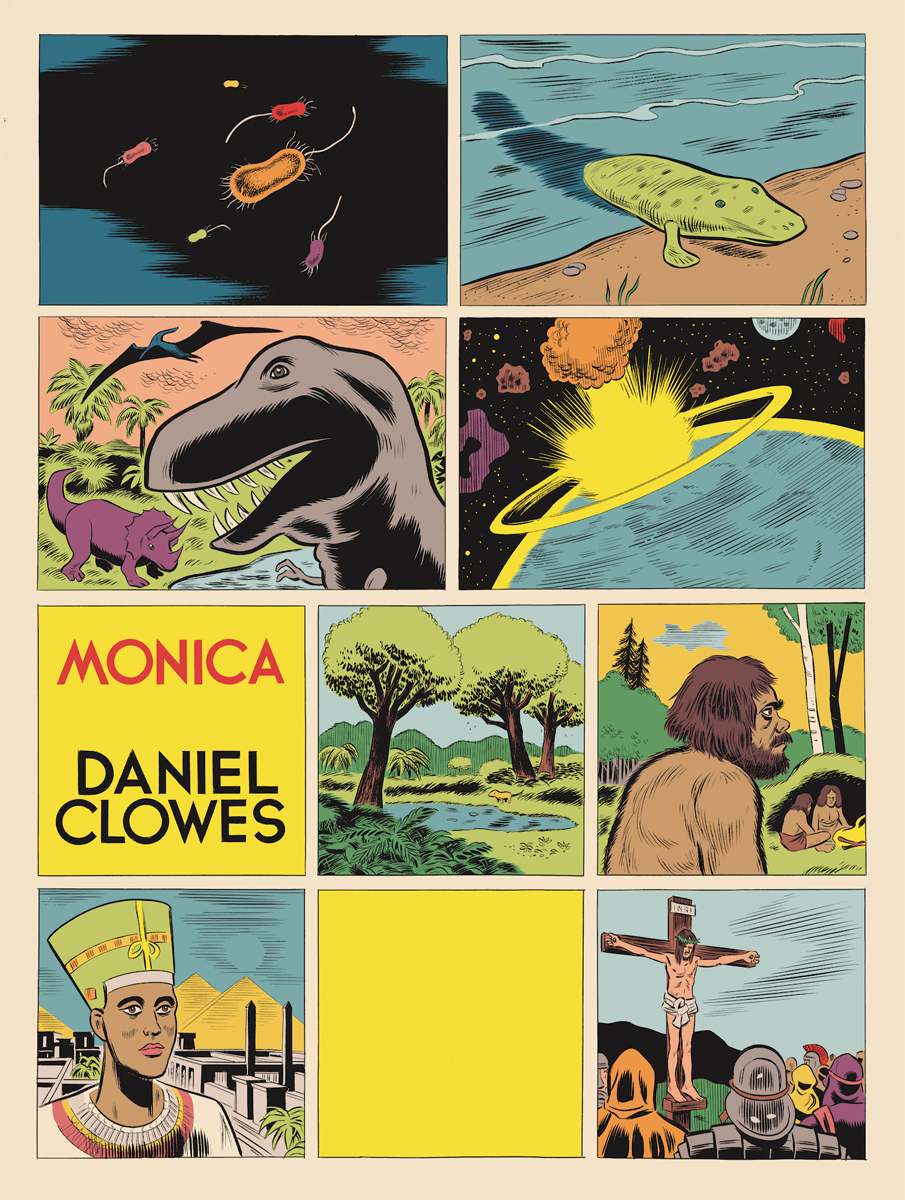

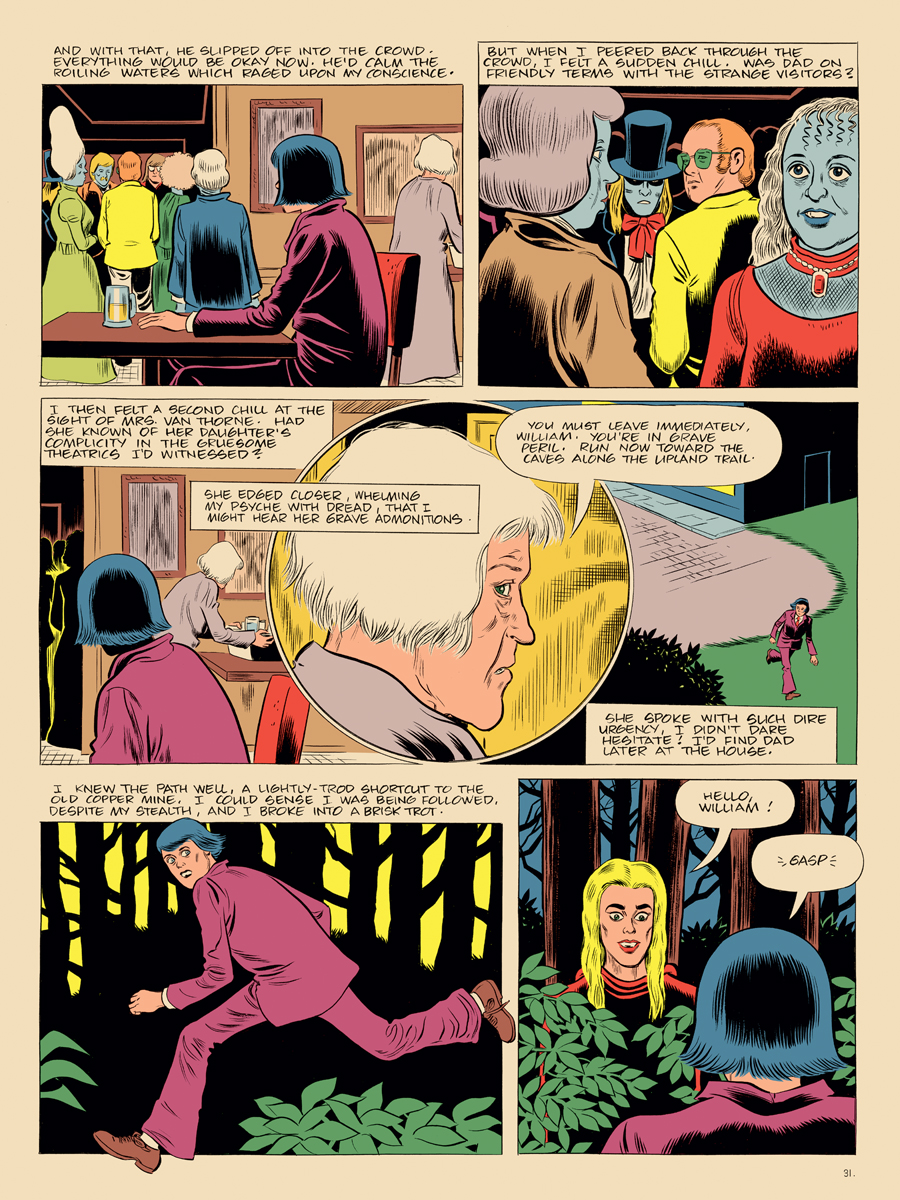

Monica’s most Hawthornean moments come in “The Glow Infernal,” an entr’acte between the “Pretty Penny” and “Demonica” chapters of the title story. It reads like one of Hawthorne’s gothic parables retold in the visual vernacular of Tales from the Crypt. The anachronistic syntax is right out of “Young Goodman Brown” (“She edged closer, whelming my psyche with dread, that I might hear her grave admonitions”), as is the folk-horror setting, a tangled wood where Clowes’s purehearted protagonist, William, stumbles on a cult of blue-skinned weirdos offering up a blood sacrifice to their Lovecraftian deity, “the bleeding thing.”

Of course, Clowes being Clowes, we’re nagged by the suspicion that we’re meant to read the story at an ironic remove, as creepy yet campy—a suspicion reinforced by his visual rhetoric. Densely referential, polyvalent, and—a word that’s now officially cringeworthy, but was all the rage in Eightball’s heyday—postmodern in its knowing use of genre tropes and signature styles, Clowes’s work is always in dialogue with the comics medium.

In Monica, he walks the line between homage and parody, appropriating—and interrogating—the comic books and Sunday funnies he grew up with. The eponymous feature story is drawn in a fine-lined, realistic style reminiscent of 1960s romance comics as well as the Bronze Age Superman artist Curt Swan, though Clowes nods, in the story’s weirder moments, to the brain-melting psychedelia of Steve Ditko (Spider-Man, Doctor Strange) and, in the “Glow Infernal” scene where William discovers a puddle of deliquescing townsfolk, their features running like candle wax, to the deliriously gross art of EC Comics legends like Al Feldstein and Graham Ingels. (The town blighted by the “great corruption” is named Ingelwood.)

But the weltschmerz that shadows “The Glow Infernal” is the opposite of irony. Returning, Rip Van Winkle–like, to a hometown strangely altered, William is shocked by the decay and degradation all around him. Though he’s only been away four years, the ravages of time have taken their toll on the house he grew up in, now fallen into “grievous disrepair.” The “elegant, stately” headmistress of his secondary school has been reduced to an abject drudge mopping the local beanery, her spirit crushed by life. Portentously, Ingelwood’s graveyard has been desecrated and the old church torn down, its passing marked only by “a ghastly absence on the skyline.” Hanging over everything is the melancholy of lost time and lost innocence: William’s innocence, but also America’s, as in Hawthorne’s “May-Pole of Merry Mount,” about a mythic arcadia whose pagan “wild mirth” is stamped out by joyless Puritan theocrats.

The story ends, paradoxically, on an ironic note. Transmogrified into a freakish divinity, half-man, half-tree, William saves the “once-bedeviled townsfolk” from the tyranny of the blue-skinned cultists—in exchange for their slavish devotion. Oh, and “the blood of their vanquished” former tormentors, which will nourish his roots. Once a true believer “purified in the blood of Christ,” he’s now “the focal center of all human existence,” the jealous god of “the one true religion.”

Is he Ingelwood’s savior, the hometown boy made God? Or a self-absorbed loner endowed, by who knows what cosmic logic, with godlike powers—like, say, Andy, the brooding high-school outcast in Clowes’s story The Death-Ray (2004), who discovers that smoking cigarettes triggers his paranormal ability to transform a toy ray gun into a terrifying instrument of vengeance (or even just misanthropic spite)? (Like every creator, Clowes makes his creations in his own image. “I am this dime-store god creating this stuff,” he said in the Raeburn interview.)

From Monica. Courtesy Fantagraphics.

Monica is Clowes’s first graphic novel since the Trump presidency. The nonstop trauma of those years changed the way he looks at the world—and his work. The nasty, misanthropic edge of early Eightball stories like “I Hate You Deeply” (from the second issue of the series, whose 1989 debut promised “An Orgy of Spite, Vengeance, Hopelessness, Despair, and Sexual Perversion”) isn’t the satirical scalpel it used to be.

“I think all my cynicism was warranted,” he said in a 2020 interview, “but you almost can’t do that anymore. I mean, it sort of felt like that was safe during a time where I thought that the bulk of the world was rational and [then] to see this willful avoidance of obvious reality and to not see what a classic American con man [Trump is, with] all the qualities of a con man from a Herman Melville story . . . it’s just deeply troubling that people would want to believe in that.”

In an America that feels more and more cartoonish, as if the farcical horror of Eightball has bled off the page into everyday life, it’s the cartoonist’s job to show us reality.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and the author of four books, most recently, the biography Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. He has taught journalism at NYU and “dark aesthetics” at the Yale School of Art; been a Chancellor’s Distinguished Fellow at UC Irvine and a Visiting Scholar at the American Academy in Rome; and published in a wide range of publications, from the New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, and Wired to Cabinet, Hyperallergic, and the LA Review of Books.