Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

In Diane Seuss’s sixth collection, a cobbling together

of forms and forbears.

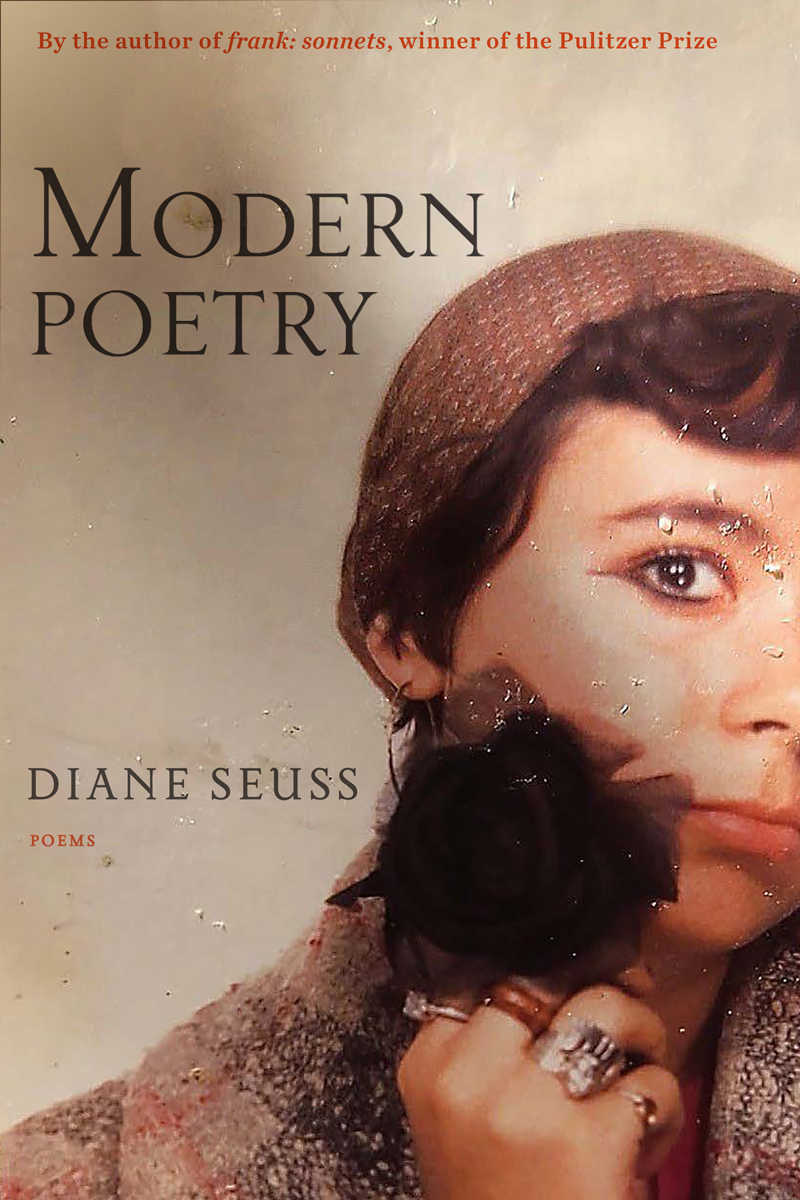

Modern Poetry: Poems, by Diane Seuss, Graywolf Press, 112 pages, $26

• • •

In her Pulitzer-winning frank: sonnets, Diane Seuss wrote: “The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without. To have, as my mother says, a wish in one hand / and shit in another.” Form and content, stricture and extravagance, ideals and dirt, tradition and individual talent—these (very likely false) distinctions occupy Seuss a lot, it appears. Poetic form is a vital container, but in her hands it tends to spill over. The lines of a sonnet may stretch on the page like lazy limbs, a close-fitting structure start leaking voluptuousness or obscenity. In “Curl,” the second of forty-one pieces in Seuss’s new, sixth collection, Modern Poetry, she writes: “It seems wrong / to curl now within the confines / of a poem. You can’t hide / from what you made / inside what you made // or so I’m told.” Seuss’s work is an intimate, extravagant inquiry into how, if at all, such confines confine.

This is in part a book about how she became a poet. Modern Poetry takes its title from both the earliest textbook Seuss recalls from her childhood, and an introductory literature course she took at college. A first confinement, you might say: thrilling as they would prove in time, the names in her tyro canon were mostly male and all of a certain class. Nor did they seem at first very modern. Theodore Roethke with his greenhouses, Gerard Manley Hopkins all “fucked up . . . tongue twistery and depressed.” The young Seuss resisted Sylvia Plath: “I didn’t trust blondes . . . I wanted to love Sylvia, but to love her would mean // loving someone who would have hated me.” When another student called Plath a “charlatan,” however, Seuss started to identify: “Who isn’t a quack at eighteen?” Still, she flunked out of college and only later read the women who would reorder her poetic universe: “Margaret Atwood. Toni Morrison. Adrienne Rich. / Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Plath. Sexton. Lorde.” Where had Emily Dickinson been in Modern Poetry? “A horse straining at the bit // in the direction of free verse.”

The sense of a poetic Bildung in the title poem is continued in “My Education,” where Seuss refers to “my unscholarliness, my rawness” and reveals: “I was a poor student, disengaged from the things / I didn’t need.” It is because, she says, she was born in a “cobbled” (very Hopkins word) landscape: that is, lumpy, variegated, but also provisional and improvised, cobbled together. Seuss grew up in rural Michigan: “the cobbled lushness of the trees, / and the arbitrary drift of brown spots / on to the white cows in the meadows, / and the wireworm-filled tunnels in the morels / at the base of dead cherry trees.” In this realm there is no system, no plan, no particular ambition. But the feeling of “foraging for supplies” is also the life of a semi-orphan. Seuss’s father died when she was seven years old. In “Ballad,” she dreams a familiar dream: the long-dead parent dug up again, damp boards and a drawerful of bones. She recalls her mother turning up early to collect her from school, refusing to come straight out and say what had happened: “You know why I have come for you.”

It’s possible to overstate the extent to which the early death of a parent determines the shape of a life. But a writing life? The loss tends, I think, to exaggerate both the adult writer’s desire for the order and control of literary form and a contending belief that all is unformed, subject to sudden swerves toward chaos and night, so why not let it fall apart? There is a strange lightness and liberty in the absence of at least one voice of steadying wisdom—an angry refusal to look back and learn, the temptation of nostalgia and a hatred of its lure. In “Weeds,” Seuss writes: “The danger / of memory is going / to it for respite. Respite risks / entrapment, which is never / good.” She has described (in an interview for the New York Review of Books) the voice that utters these words as “the oversoul speaking to the undercarriage, the walking-around self.” It’s unclear which of these is the educated self, which the cobbled one.

What then is poetic form: oversoul or walking-around, parent or child, wisdom or adventure, carrion or comfort? Modern Poetry is not just full of poet’s names (we haven’t even touched on John Keats, the book’s darkling patron saint); it’s also rich with named forms that sometimes accord with the apparent design of the poem, sometimes not so much. These poems frequently propose themselves via their titles as various, more or less definable modes: “Ballad,” “Rhapsody,” “Villanelle,” “Threnody,” “Ballad in Sestets,” “An Aria,” “Coda,” “Ballad That Ends with Bitch,” “Little Fugue with Jean Seberg and Tupperware.” Certain regularities of line and stanza are in evidence; there is a single sonnet (“Little Song”). But, time and again, there’s also the undoing of the rigors or consolations of form—effected or argued at the level of sense and sentence rather than overall shape. “Little Fugue State,” with its musical-melancholic title, is a short headlong rush into unknowing, all made of negatives: “not even . . . nor why . . . nor where . . . not that . . . nor this . . . nor poetry.”

I fear that, like Seuss’s first poetry teachers, I may have made Modern Poetry sound too austere. The fight with form is also on behalf of a wildness and richness of life as well as motif. Constraint (poetic or economic) is countered with the pure hedonism of neglected communities and micro-scenes. In “Juke,” Seuss asks: “What kind of juke do you prefer? / For me, it’s the kind with three / songs and thirty-seven blank / title strips. Three songs, and two / are ‘Luckenbach, Texas.’ ” There is an awful lot of music in Modern Poetry, both as subject and poetic sound—and none of it is polite or restrained, unrolling instead as raucous “antisong.” “The song choices were limited, / so the grooves were dug deep,” Seuss writes—which seems as apt a description of her relationship with language as with landscape, memory, bodies and things, other matters of life and death.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities, Suppose a Sentence, and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on Ambivalence (on education) and Gone to Earth (on Kate Bush).