Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Aphorisms and aesthetics: a new translation reveals the strange stylings of writer, artist, and filmmaker Jean Cocteau.

Secrets of Beauty, by Jean Cocteau, translated by Juliet Powys,

Eris, 47 pages, $15

• • •

In his foreword to these brief reflections on beauty and poetry, the scholar Pierre Caizergues describes Jean Cocteau as “one of those magicians who, having announced that they are going to reveal the secret of their trick, immediately perform another, even more amazing one.” The writer François Mauriac said it with more economy: Cocteau was a “ubiquitist.” It’s true he was everywhere, and aspired to do everything; his ambitions, he said, grew in every direction, like his hair and teeth. Cocteau was the teenage dandy and poetic prodigy who attended the sickbed of Marcel Proust, was a librettist for Stravinsky and Diaghilev, a novelist and autobiographer, the director of indelibly strange films, a cross-disciplinary queer artist in a lineage that includes Oscar Wilde, Andy Warhol, and Derek Jarman. But also: a restless and buzzy frequenter of surfaces, a gadfly whose addictions to style and celebrity mark him out as something like the anti-Duchamp of the twentieth century.

The magician in question was a celebrated, and in some circles distrusted, fifty-five-year-old when, in March 1945, he set out from Paris to Graçay to see his lover, Jean Marais. (The leonine actor plays the beast in Cocteau’s antic and sumptuous 1946 film La Belle et la bête.) On the way back, Cocteau’s car broke down and was towed to Orléans. Now train-bound to Paris, the recently blocked poet grabbed envelopes and endpapers and began to write: aphorisms, fragments, aperçus, mostly concerning his aesthetic attitudes. Secrets of Beauty—the main text runs to just thirty-four pages in Juliet Powys’s new translation—was published in the journal Fontaine two months later. In common with Cocteau’s whole oeuvre, some of it is slight enough to fly out a train window. When he is not succumbing to banality or self-justification, though, Cocteau also essays here an off-the-cuff but compelling defense of his own stripe of spooky, mock-classical modernism.

What does “poetry” mean for Cocteau? Not something confined to actual poems, which are addressed in this text alongside the poetry of cinema, novels, music, paintings, children, the French language. Consult his plays and films—or even the place I found him first: the many 1980s music videos that cannily and campily usurped his imagery—and the answers appear like familiar brand logos, or the well-trod stations of Cocteau’s aesthetic cross. Time and again, things come to life, myths are animated, another world touches ours. A statue stirs and speaks—in Le Sang d’un poète (1930), it’s Lee Miller, in her only film performance. The fate of Narcissus is endlessly recast and rehearsed; will he fall through a liquid mirror into the void, or make love to his own double? Angels, masks, detached limbs or mouths: Cocteau’s is an art of motifs, and motifs risk becoming exhausted. In Secrets of Beauty, he admits as much: “We abused the angels. . . . We must bid them farewell.” Still, he values a heraldic quality (here discerned in Picasso) which he had declared at the start of Le Sang d’un poète: “Every poem is a coat of arms. It must be deciphered.”

It is sometimes clear that when Cocteau says “poem” in these pages he means something written, and written in verse. He hymns the “damned women” and “strange flowers” of Baudelaire. There are occasional assaults, without naming any names, on the failings of contemporary poets and their publics. A lot of poetry, says Cocteau, is really “rhythmic prose” that dupes the reader. Many young poets are simply in love with words. If this sounds like conventional middle-aged literary griping, there is a good deal more in this very midline. Children are poets, until they are not. “Beauty hates ideas. It is sufficient to itself.” Poets find it hard to live because they are essentially posthumous. “A man without a drop of passionate blood will never be a poet.” In his 1947 autobiography, The Difficulty of Being, Cocteau distinguishes between the “intimidating” labor of writing at a table and his casual practice of writing anywhere and at any time, on his knee. There is a little too much knee-writing in Secrets of Beauty.

But then he surprises you, as if you’re watching one of his films, and the figures on the fireplace are rolling their eyes, a young girl is crawling across the ceiling, the underworld is broadcasting via the car radio. Here as elsewhere Cocteau makes much of his proximity to, and family feud with, the Surrealists. “All beautiful writing is automatic,” he says, but seems to only half-believe it. In some respects, Cocteau was as much attuned to chthonic or perverse energies as André Breton and crew. He just reached the depths with a lightness, discipline, and “hygiene” that (as with Wilde or Warhol) don’t preclude profundity: “The great loneliness of a poem is to be at once the height of autocracy and the height of anarchy.” Behind it all, a “silence” that Cocteau insists upon but is hardly likely to reflect on at length. (“The poem as the blood of silence. The poem as the cry of silence.”) Does he mean anything akin to the postwar “silence” of Samuel Beckett or John Cage? I suspect they both learned small things from him about stage and spectacle—but the knee disallows much speculation.

Cocteau was sometimes a labored aphorist, sometimes possessed by Wildean genius: “Victor Hugo was a madman who thought he was Victor Hugo.” In Secrets of Beauty, the epigrammatic tone dominates. “A poem is not written in the poet’s native language.” “I will repeat myself until I die, and after I die.” What happens when this voice turns away from deathless aesthetic verities and has to face present historic facts? The spring of 1945—was Cocteau keen to separate his loftily apolitical art from accusations of reaction, and worse? He had made certain unfortunate remarks about the French attitude toward Hitler; during the war, he remained friends with Ernst Jünger and Arno Breker, Hitler’s favored sculptor. Now, he places himself on the side of the Resistance, balks at those rulers who see artists as payrolled mouthpieces, and declares: “A poet is always under an Occupation which he resists.”

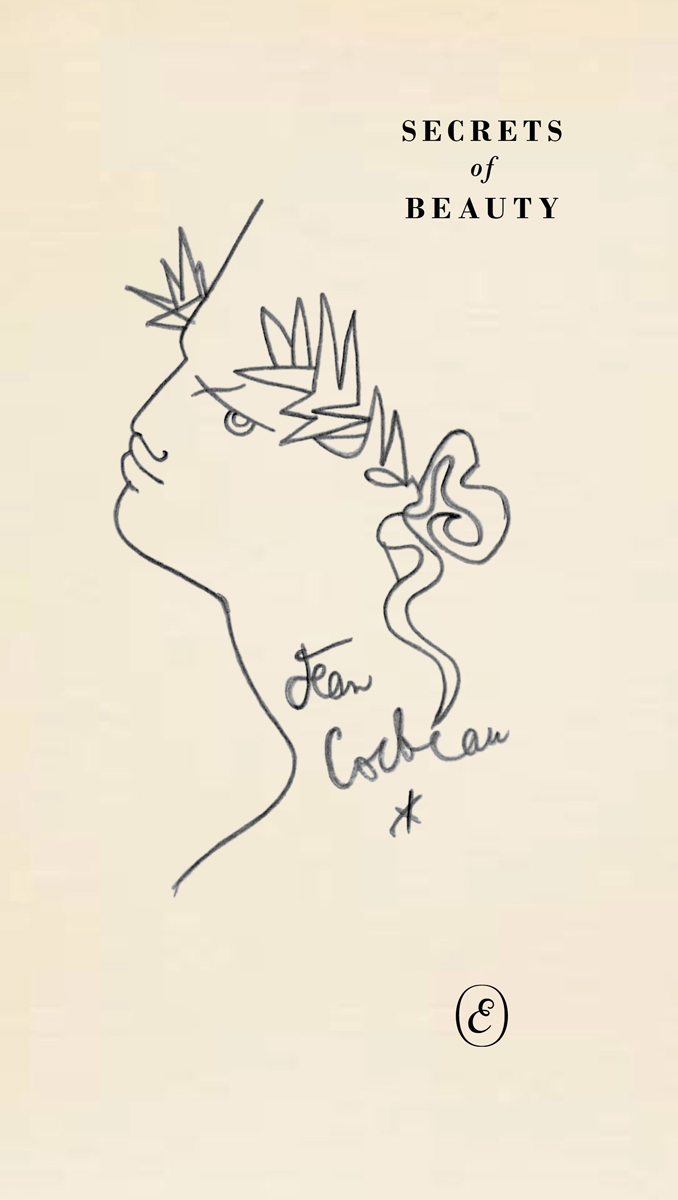

Such flourishes were not enough for some. Breton called Cocteau “the arch impostor, the born conman.” It’s frequently the fate of artists who fling their talents at too many forms to be swiftly forgotten, consigned to the second tier of dilettantes and mere impresarios. If something survives of Cocteau, it is first the films, and then the very performance of style itself, which casts all his work, good and bad, into a giddy sort of doubt—it winks away here like the star he always drew below his signature.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities: On Art and Fascination, Suppose a Sentence and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on a book about Kate Bush, and another on aesthetic education.