Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

At the Met, an expansive retrospective of the painter’s work.

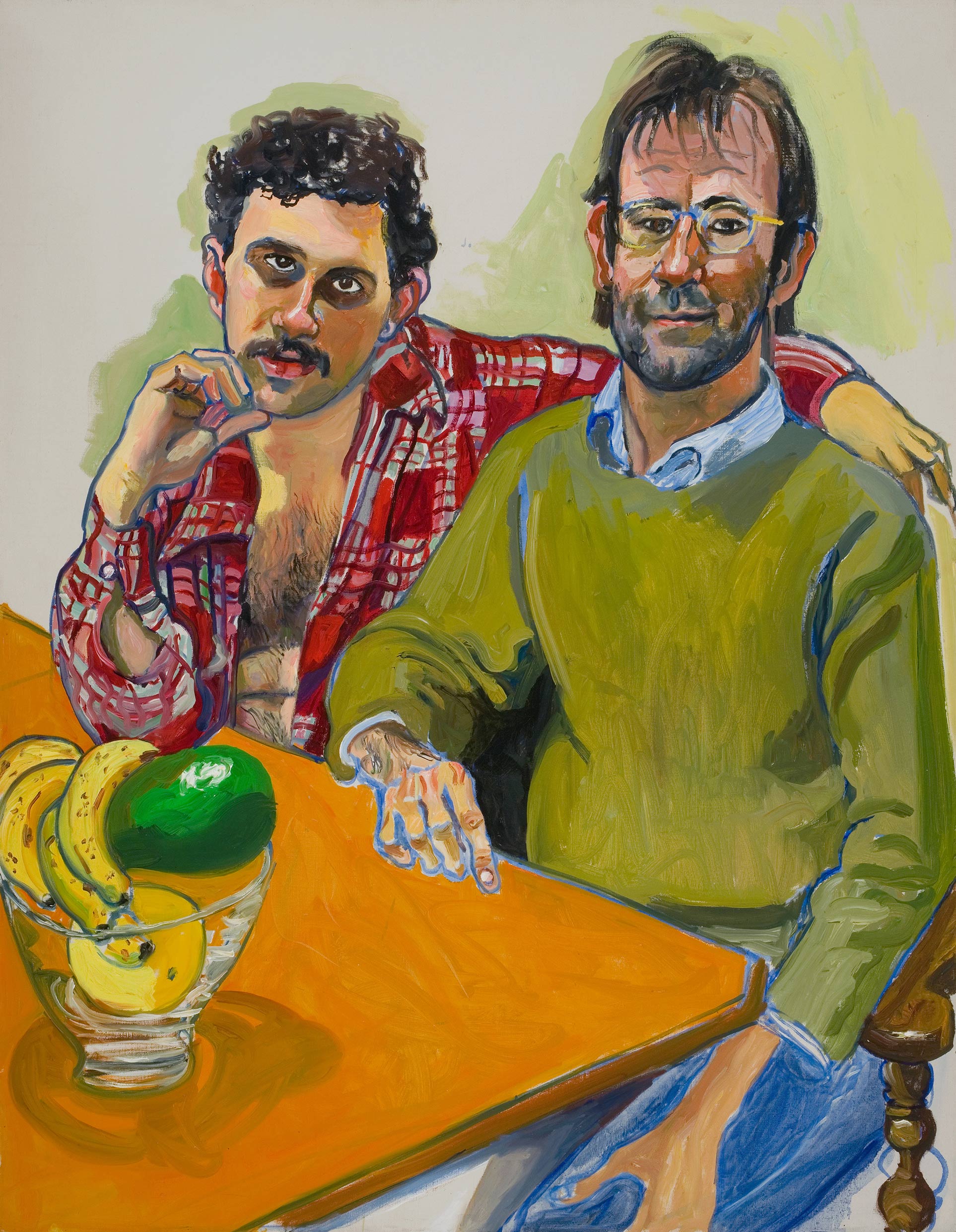

Alice Neel, Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian, 1978. Oil on canvas, 46 3/4 × 36 3/4 inches. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

Alice Neel: People Come First, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through August 1, 2021

• • •

It’s nice to see Alice Neel opposite Francisco Goya, their respective exhibition banners flanking the Met’s main entrance, pulled taut between the archways of the façade. The old master’s Seated Giant (ca. 1818), with its muscled figure, pensive beneath a sliver of moon, plays night to Neel’s day. Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian (1978), a bright double portrait, brimming with life, represents her massive retrospective, People Come First. The painting shows a gay couple at a table, outlined in blue and haloed by fast lemon-lime brushstrokes. One of the guys (Hendricks) appears a little stiff in his green sweater, while the other (Brian Buzcak), his shirt open, slouches with an arm slung around his boyfriend, gazing at Neel—and now, a lucky stretch of Fifth Avenue—with platonic bedroom eyes. A charming feature in the composition’s foreground is partially cropped out in the huge reproduction, and the lettering of the show’s title obscures it a little too. Inside the museum, visitors can see that the radiant painting includes a bunch of bananas spooning in a glass bowl. It makes the scene a touch more louche, and stands as a winking reference to the storied tradition of allegorical fruit arrangements in European art history.

Alice Neel: People Come First, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

This crowd- and critic-pleasing exhibition, the first New York survey of Neel’s work in two decades, and the city’s largest ever, is set to be a blockbuster. To give just a taste of the effusion, Roberta Smith’s review for the New York Times bears the headline “It’s Time to Put Alice Neel in Her Rightful Place in the Pantheon.” The endorsement is something of a vindication (though the artist, who lived from 1900 to 1984, is not here to enjoy it). Hilton Kramer, writing for the Times in 1974, panned Neel’s first retrospective at the Whitney, writing, “There are ineptitudes here . . . that are not a matter of style but of basic competence.” Another snub—funny now that the Tisch galleries are bursting with the painter’s enthralling, inarguably influential canvases—was delivered by Met curator Henry Geldzahler. When Neel approached him after he left her out of a major 1970 survey, asking if he’d include her in the next one, he responded, “Oh, so you want to be a professional?”

Alice Neel: People Come First, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen. Pictured, right: Alice Neel, Ethel Ashton, 1930.

The corrosive sexism of her time wasn’t her only disadvantage. Neel was a figurative painter, in principle and by nature. What she was doing, certainly for much of her career, didn’t fit in. Facing the headwinds of Abstract Expressionism, her Postimpressionist, social-realist style evolved and loosened up significantly—as expressed in her confidently meandering lines, confrontational color, her “unfinished,” empty backgrounds—but she fundamentally stayed her course. She was a communist; her identity as an artist who painted “pictures of people” (the term she preferred to “portraits”) was inseparable from her politics. Among the show’s Depression-era works are Investigation of Poverty at the Russell Sage Foundation (1933), in which a group of well-heeled social scientists interview a despairing subject, and a 1935 portrait of union leader Pat Whalen, his heavy fists resting on the Daily Worker. But Neel soon shed propagandistic themes. Her frank eroticism, diverse subjects, and nonchalant, unconditional acceptance of the human body form a profound politics of their own. Even before the two works just mentioned, it’s apparent she’s on to something with 1930’s Ethel Ashton, a starkly unsentimental nude that Neel painted from above.

Alice Neel, James Farmer, 1964. Oil on canvas, 43 3/4 × 30 1/4 inches. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

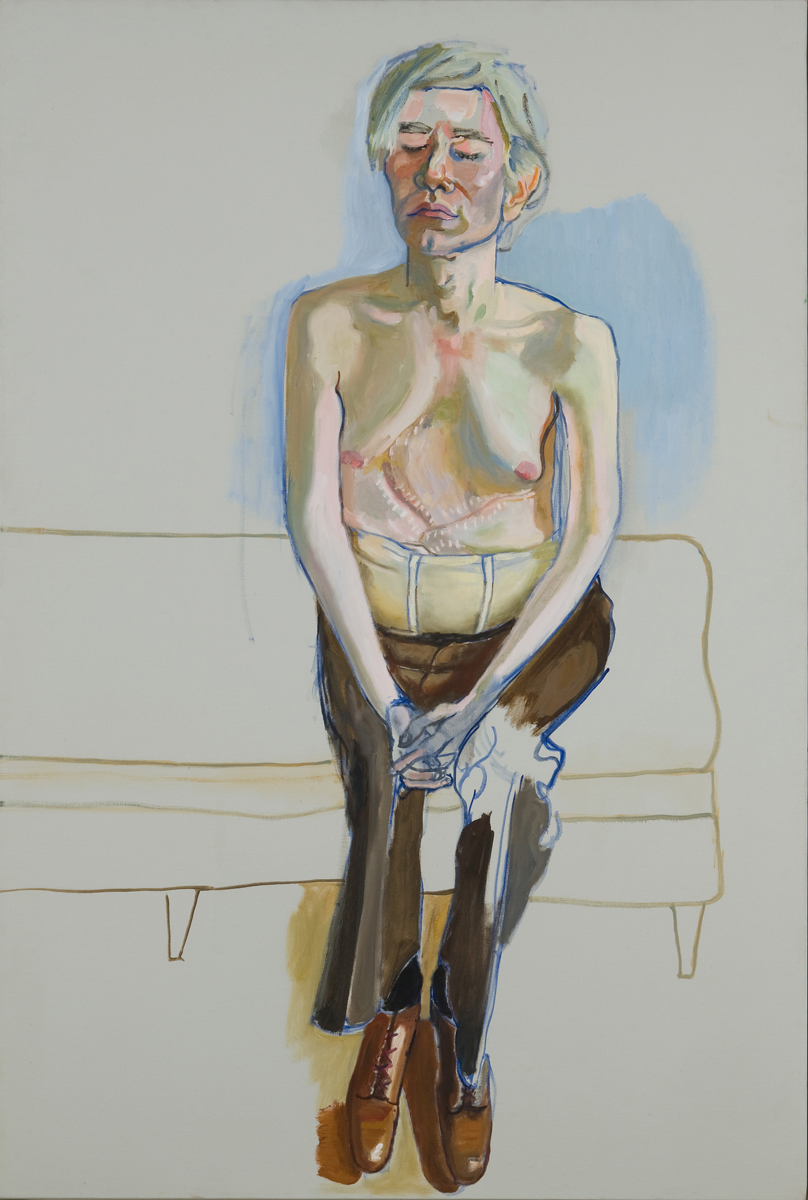

Considering Neel’s five decades of output while living uptown (in Spanish Harlem beginning in 1938, and then on the Upper West Side, where she moved in 1962), Hilton Als has written that it was not (only) how she painted but who she painted that put the Geldzahler types off. People from her neighborhoods, as well as civil rights leaders, such as James Farmer, and Black literary figures, including Alice Childress, sat for her. “Had Neel restricted her canvas to the white world, she would have been celebrated sooner, swear to God, because then her detractors . . . would have seen themselves, which, in the art world at least, is always rewarded,” Als points out. He curated the pivotal Neel exhibition Uptown at David Zwirner in 2017, which focused on her portraits of people of color; I’m glad I had my lingering impressions of it to bring with me to People. It’s more interesting to think about Neel not as a misfit at the margins of past movements—and not even as the maker of such arresting, enduring images as her 1970 picture of Andy Warhol, his eyes closed and torso traversed by scars—but within the context of figurative painting’s present renaissance, which is led by artists explicitly engaged in the project of decentering or disintegrating the white world.

Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, 1970. Oil and acrylic on linen, 60 × 40 inches. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

Neel used portraiture to forge or seal social bonds, rather than to affirm hierarchy and distance, and this appears in her later works as a chatty and soul-reading energy that zeroes in on faces and hands, sometimes penises, or—as in her knockout 1970 portrait of Factory superstar Jackie Curtis and her companion Rita Redd—feet. Earlier, though, there is perhaps more brooding self-reflection in her art. When Neel painted the exquisite, emotionally complex work The Spanish Family (1943)—which depicts a family of four, no father—she was herself raising two young sons alone. There’s a raw empathy here for the serious young woman at the composition’s center, keeping it together with a baby on her lap.

Alice Neel, The Spanish Family, 1943. Oil on canvas, 34 × 28 inches. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

Neel lost her first daughter to diphtheria, in 1927, and her second to her husband, in 1930, when he took the child to Cuba—heartbreaks that precipitated Neel’s hospitalization that year. Her clear-eyed insight into motherhood as work, as mourning, and as an embattled or depleted state, as well as a joyful one, is evident in the particular intensity and unforced radicalism of her portraits of pregnant women and mothers. People does a beautiful job highlighting this tremendous strength. The painting that first greets visitors is the bracing masterpiece Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978), which portrays its nude subject as expectant in every sense. She sits up straight, making space for her ballooning trunk, a veined breast foreshadowing her grueling role in the months to come. Elsewhere—in Carmen and Judy (1972) or Nancy and the Twins (1971)—breastfeeding is both a humdrum fact of life and a quietly saber-rattling display of feminist immodesty.

Alice Neel, Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas, 57 3/4 × 38 1/2 inches. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

It’s a perspective of course lacking in Van Gogh’s gloriously unhinged painting Madame Roulin and Her Baby (1888), which the Met has installed in the exhibition alongside a few other relevant historical paintings (by Chaim Soutine, Jacob Lawrence, and more), drawing the context and prestige of the museum into sharper focus. The inclusions are apt: Neel enjoyed comparing and contrasting herself with the greats. In a radio interview, she once paraphrased Cézanne saying he liked to paint portraits of those who’d grown old in the countryside. “I’m just the opposite; I like to paint people torn apart by the city,” she mused. It shows. For New Yorkers, worse for wear as we head into summer, Neel seems the perfect painter of and for the people, her so-called ineptitudes now revealed as the mark of not just a professional, but of a new, or newly visible, member of the pantheon.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.