Rhoda Feng

Rhoda Feng

Side effects may vary: in Lucy Prebble’s play, love and romance go head-to-head with an experimental antidepressant.

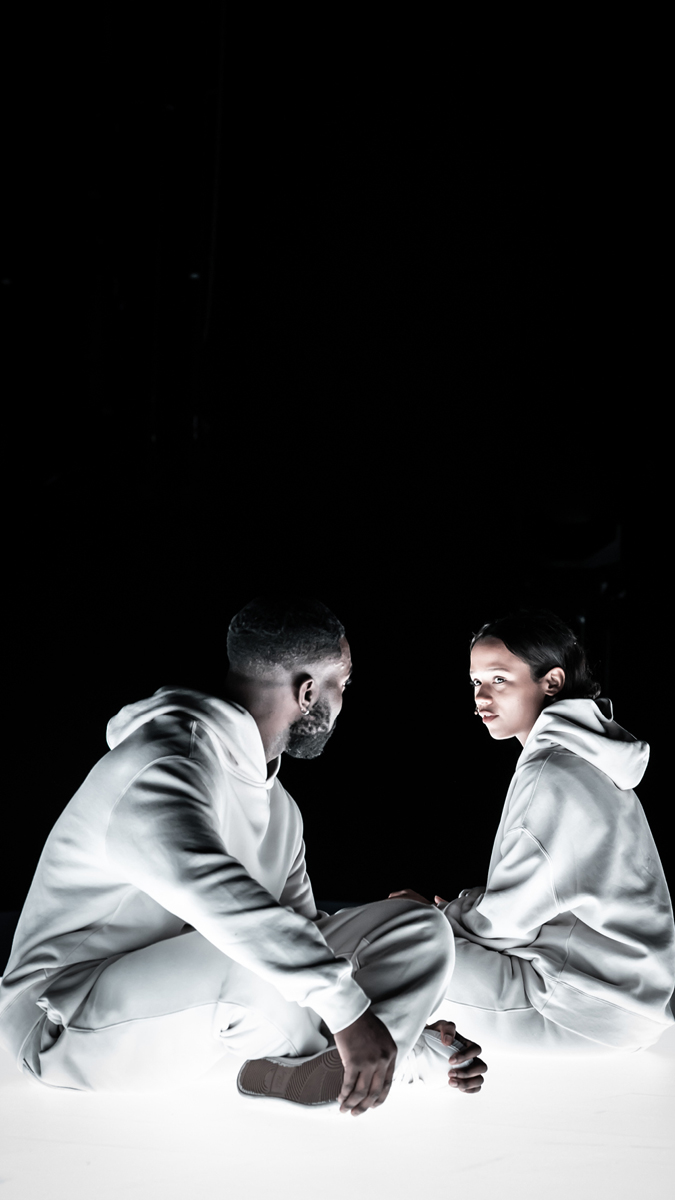

Paapa Essiedu as Tristan and Taylor Russell as Connie in The Effect. Courtesy the National Theatre. Photo: Marc Brenner.

The Effect, written by Lucy Prebble, directed by Jamie Lloyd, the Shed, 545 West Thirtieth Street, New York City, through March 31, 2024

• • •

In 2006, Parexel, a US clinical research company, conducted a trial for an experimental treatment targeting leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis. Eight healthy men enrolled; two were given placebos and six were administered the medication at a north London hospital. Shortly after the study began, those who took the drug experienced severe adverse reactions, including organ failure, leading to their hospitalization in critical condition. Sparking widespread concern, the incident raised questions about the safety and ethics of such trials.

Lucy Prebble’s The Effect takes a buccal swab from the Parexel fiasco, but as a dramatization of what can go wrong in medical experiments, it could have drawn from any number of real-life disasters. “The history of medicine is just the history of placebo, since we know now almost none of it worked,” says a doctor in the play. That the character who utters this is a Black woman gives the line an extra punch: the history of medicine is, after all, shot through with racism. The incarnation of The Effect running through the end of this month at the Shed’s Griffin Theatre has been slightly updated from its original version, which premiered in London in 2012, and now stars an all-Black cast. But the show’s central nervous system remains essentially the same, involving two participants in a phase one trial for a new antidepressant, which goes off-piste in a matter of weeks.

Paapa Essiedu as Tristan and Taylor Russell as Connie in The Effect. Courtesy the National Theatre. Photo: Marc Brenner.

Dressed in matching white sweats, Connie (Taylor Russell) and Tristan (Paapa Essiedu) move about on a runway starkly suggestive of a petri dish (Soutra Gilmour designed the sleek set). They have a meet-uncute holding cups of urine; Tristan gently thorns Connie about her squeamishness over her sample (“Why you hold it like that, it came out of you just now!”) before persuading her to give it to him so she doesn’t have to make the trip to the doctor’s office. Actually, the cups are notional. The show is directed by Jamie Lloyd, and, as with his bare-bones A Doll’s House and Cyrano de Bergerac, the stage is almost completely bereft of props.

Michele Austin as Dr. Lorna James and Taylor Russell as Connie in The Effect. Courtesy the National Theatre. Photo: Marc Brenner.

The actors are moated by audience members, who sit on raised platforms, observing the action and each other across the catwalk. Glowing white floor panels (Jon Clark did the lighting) illuminate the characters when they field screening questions from a doctor, as if to evoke parts of the brain lighting up in an MRI. Over the course of four weeks, they will be given titrated dosages of a drug designed to stimulate dopamine—“the rush you get if something exciting happens.” Dr. Lorna James (Michele Austin) administers the pills, records the participants’ behaviors, and reports her findings to Dr. Toby Sealey (Kobna Holdbrook-Smith), a dapper psychiatrist who just happens to be her former lover. On elevated doses, Connie and Tristan report feeling “more awake” as well as experiencing racing thoughts and heightened sex drives. In other words, they exhibit all the classic symptoms of falling in love. (The medication’s effects are eerily similar to that of LuvInclyned, the fictional psychotropic specimen that can induce “a deep sentimental longing” in George Saunders’s 2010 dark Pharma fable “Escape from Spiderhead.”) Yet Connie, rational psychology student that she is, starts to suspect that either she or Tristan is on a placebo; the thought that she doesn’t love him the way he loves her is macerating.

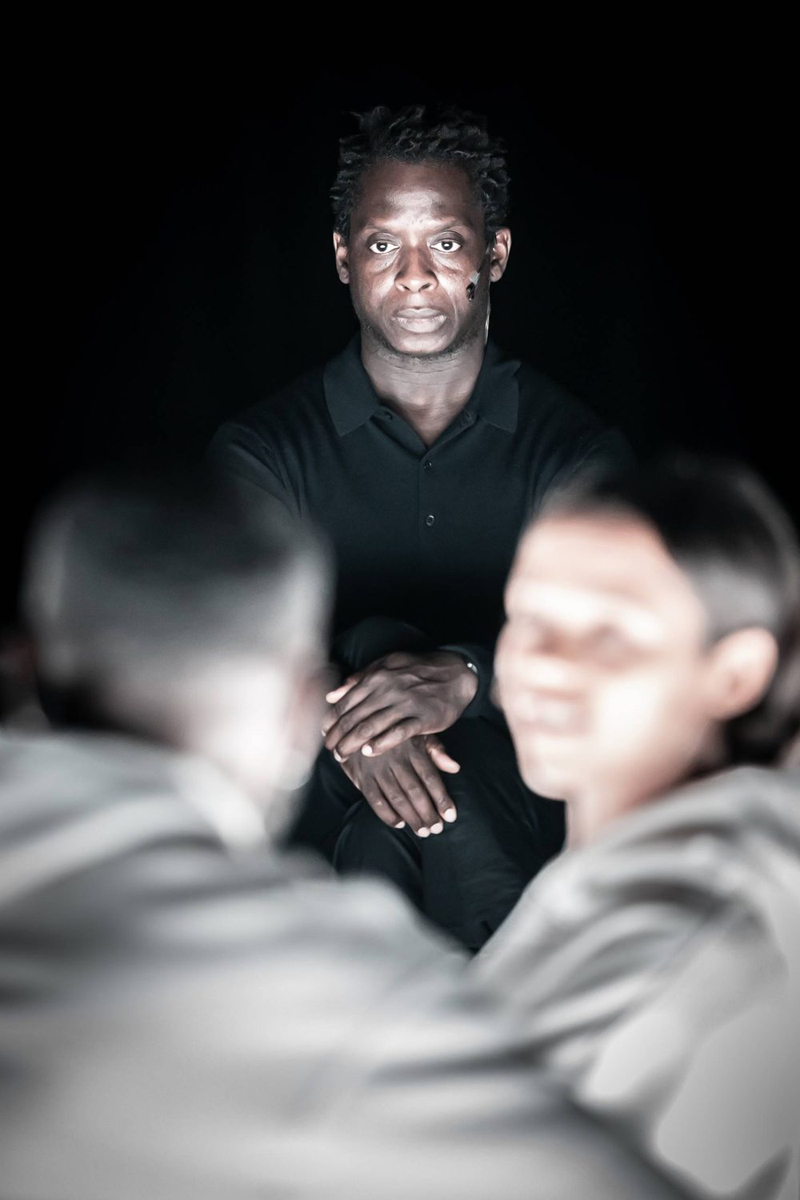

Kobna Holdbrook-Smith as Dr. Toby Sealey (background), Paapa Essiedu as Tristan, and Taylor Russell as Connie in The Effect. Courtesy the National Theatre. Photo: Marc Brenner.

But as the dosages are increased even further, more complications ensue. The question of who might be on a placebo is displaced by a more urgent one: Will the drug jeopardize their health? At 100 mg, the side effects are already alarming: the participants are addled, experience bowel problems, and one of them starts exhibiting “aggressive behavior and paranoia.” With Toby’s prodding, Dr. James will eventually administer a final dose of 250 mg. Scoring the adrenalized anticipation is George Dennis’s percussive beat, which vibrates in your chest cavity.

Michele Austin as Dr. Lorna James in The Effect. Courtesy the National Theatre. Photo: Marc Brenner.

For nearly all the play’s one hundred minutes, the doctors are sentried on opposite sides of the stage, occasionally moving to the center to explain how the brain keeps the body in homeostasis or to share something of their medical history. In one of the most affecting moments, Dr. James expresses the torment of living with depression: adopting a battlesome voice, she berates herself for being “lazy,” for “decaying,” for being a “coward,” for ruining people’s lives. It’s difficult to watch, but watch we do: her inner demons, successfully repressed in the play’s first half, now trail her with the tenacity of a documentary film crew. Did Toby charge her with overseeing the trial despite her history of depression, or because of it? He ended their affair a few years ago partly because of her condition; if he has his druthers, depression will one day be banished by drugs. For her part, Dr. James insists that depressives tend to have a more accurate view of the world, and she doesn’t wish to be “cured” of anything.

The way that the play’s two overlapping storylines are made to bisect is a mite diagrammatic. And there’s a touch too much of an emphasis on cerebration: not only the absence of props, but the gestures alluded to, yet never enacted (the handing over of a smashed smartphone, the sharing of a newspaper, the borrowing of a mirror), all encourage us to cogitate over effects visible and invisible, manifest and latent. That The Effect doesn’t devolve into a Cartesian pensée about mind-body dualism or a sub-Stoppardian allegory about the hard problem of consciousness owes much to Russell’s and Essiedu’s fresh performances. Stepping into a role originated by powerhouse Billie Piper would be tough for anyone to manage, but Russell makes the play hers; she starts off as a reserved woman who doles out personal details as carefully and deliberately as a pharmacist dispensing prescription drugs, but becomes uninhibited to the point of feeling almost no remorse for what one doctor calls “poor decision-making.”

Paapa Essiedu as Tristan and Taylor Russell as Connie in The Effect. Courtesy the National Theatre. Photo: Marc Brenner.

As Connie and Tristan find ways to illicitly spend time together—in each other’s rooms, in an old asylum—away from the supervision of their chaperones, their romance harks back to that ur-story of young, forbidden love: Romeo and Juliet. Prebble, who has also written for HBO’s Succession, deftly balances aphoristic zingers (one of the characters refers to heart surgeons as “plumber[s] of the body”) with plainspoken poeticisms—the antithesis of the antiseptic language of science. Talking about the experience of falling in love, Connie says, “Something’s in me but it’s like it’s come from outside of me. Like having the weather inside.” The Effect has its own internal weather system: full of skittering clouds, rolling thunder, and the rare sunbeam.

Rhoda Feng is a freelance writer based in Washington, DC.