James Hannaham

James Hannaham

The pain artist: a show documents the work of a controversial performer.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, curated by Amelia Jones, Participant Inc, 253 East Houston Street, New York City, through April 4, 2021

• • •

I’ve known of Ron Athey’s BDSM-inspired ecstatic pain rituals since the 1990s, when he and other performance artists regularly packed houses at P.S. 122 (now called Performance Space New York). In those hallowed halls, Karen Finley covered her naked body in various substances, Annie Sprinkle invited us to gaze into her vagina, and Spalding Gray talked about Rhode Island. Athey, though, like Finley a target of Jesse Helms’s NEA outrage, operated in even more extreme territory, and still does, after thirty-plus years.

Onstage, he and his company pierce their bodies with spikes and slice their skin with blades. Athey stapled the flesh around tattooist Alex Binnie’s genitals, Athey pushed pearls out of his anus, penetrated himself with a dildo attached to a stiletto heel. In the piece that raised Helms’s wrath, one performer’s wounds became a “human printing press” after several two-ply paper towels absorbed the blood, and the patterns of the injuries became monoprints. (This was falsely assumed to be Athey’s HIV-positive blood, and an uproar ensued.)

Athey was devoutly Pentecostal as a child (“sainted as a prophet messiah who proselytised in tongues,” says one description), then fell hard from grace—into LA punk, drug addiction, ’80s-’90s queer culture, and HIV-positive status—so tumbling into that scene granted him a kind of shaman status. He continues to revel in it, especially in countries less hostile to transgressive art. But the solemnity, long robes, and dim lighting in which he and his acolytes often perform these shocking sacraments always point toward the eroticized suffering of Christ depicted in myriad artworks, as well as to the writings of French thinkers like Jean Genet and Georges Bataille, and contemporary body artists Carolee Schneemann, Chris Burden, and Bob Flanagan. Never do his pieces indulge in exploitation or sensationalism; instead they position Athey as a sort of underground spiritual leader.

As a queer person, I respect the extremity of this work, its cathartic potential, and its radical critique of gender norms. But as a nonreligious person of color, I find its trappings primarily geared toward Euro-Americans who, like Athey, have become disillusioned specifically with Christianity, and who find transcendence in witnessing the real physical pain of others, which I suppose I don’t. I prefer to help people when I see them in pain, but a fourth wall in the way pretty much prevents this. So to Athey’s shows, I find myself emphatically saying both Yes, do this work! and Um, I’m busy that night.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

Athey’s themes and controversies are mother’s milk for many cultural critics, who leap to put these scandalous tableaux vivants in context and defend his right to create them. Hence, it’s not surprising that Participant Inc’s retrospective Queer Communion appears in tandem with a 439-page book of the same title, its first half composed of Athey’s writings, its second of brief essays by others. That the show and the book provide a welcome distance from the harrowing experience of live Athey performances is a boon to the appreciative bystander, the performance historian, and the just plain fraidy cat.

The nonprofit Participant Inc is really the perfect venue to present this show; it’s the art space that most resembles an East Village punk-rock performance club from bygone days, a veritable CBGB of artists whose work opposes the mainstream—Jayne County, Narcissister, Christeene—its interior painted black as often as other galleries paint theirs white. Raw tin ceilings and fluorescent lights help create the impression of the aftermath of an energetic, messy concert.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

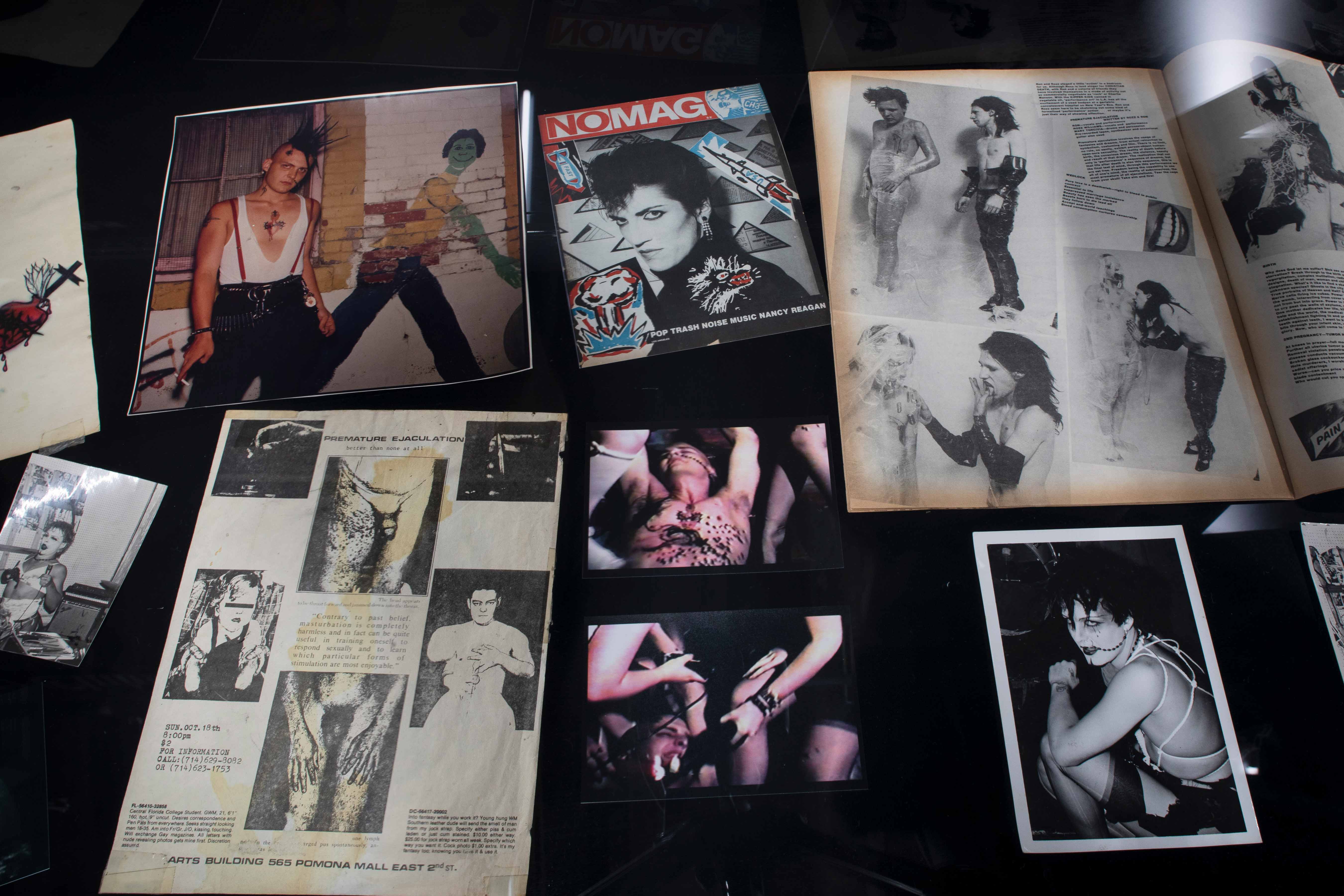

In that spirit, the Athey show consists of a wide array of artifacts from the artist’s personal and onstage lives, arranged by themed “zones” rather than a timeline: Religion/Family, Music/Clubs, Literature/Tattoo/BDSM, Art/Performance/Politics, New Work/Community, organized in stations around one large room and a darker back area.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

The copious topics presented aren’t actually separable, though. Athey constantly excavates his biography to bring back some pretty grim material, but the exuberant theatricality of the extraordinary props and costumes of his past takes over the space. For the Torture Trilogy (1992–95), Athey donned a matronly white gown equipped with an outsize bustle, in tribute to (or mockery of) Sister Aimee Semple McPherson, the larger-than-life star evangelist and founder of the Foursquare Church; this and a few other drapey, quasi-religious costumes in velvet immediately set a tone of sleazy chic. Other dazzling items—a crown festooned with prosthetic eyeballs, a pair of hip-high lace-up leather boots, a series of six dildoes on ten-foot-long sticks—accompany a number of glass cases containing smaller objects, numerous snapshots of wild early performances and backstage antics, and rare manuscripts, all surrounding a wooden pyramid, a torture device on whose apex Athey parked his high-endurance booty for three minutes during Judas Cradle, a piece created for the 2004 Visions of Excess Festival.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

If the installation throws everything at you rather than providing much in the way of guidance, that seems to be part of the point. The viewer can control their level of involvement here much better than the audience members in some of the videos looping on the far-left wall. One may watch for as long (or short) as one wishes before diving into a different aspect of Athey’s decades in the margins. To wander among the trappings adds a veneer of glamour that the performances don’t highlight in quite the same way. One can see more of the beauty rather than being overwhelmed by the gore: drawings on storyboards from previous shows, Catherine Opie’s sumptuous photos of Athey in a leather corset, a notebook with a photocopy of a photograph Scotch-taped to it of Athey as St. Sebastian, pierced with sundry arrows. Offering autonomy to the spectator does tone everything down, but the softened impact allows for a different kind of engagement, perhaps a launch pad for the unconverted. What good is subversion when everyone’s already on board?

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

It also starts to become clear that while Athey’s rituals critique and mimic those of Christianity—“building a makeshift church, of sorts, for the bulldaggers, faggots, and marginalized folks that form the luscious core of his community,” say the catalog editors—the followers of Jesus are not just compelled by ritual but narrative. Since so much of Athey’s output, though, is about action rather than storytelling per se, and that he inhabits the role of the sufferer at the center of his work, his life story and charisma are a large part of what drives interest and enthusiasm around the proceedings. A charming, lucid, and surprisingly sweet explainer of his own work—in the companion book, his writings are delightfully plainspoken and nonacademic—Athey obviously inspires a great deal of devotion, dare I say a cultlike following, especially in his performers, willing to do damn near anything for him, at least on stage.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

And if these elaborate performances of actual pain amount to surrogates for Christian ritual, sacrifice, and suffering, with Athey as profane Christ figure, the experience of visiting Queer Communion can be just as exciting as going to a religious site as a tourist of a different denomination—taking pictures, marveling at the reverence, the vestments, the chalices, the stained-glass windows—especially for those who are not already devout Atheyists.

James Hannaham’s most recent novel, Delicious Foods, won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. His next book, Pilot Impostor, a bevy of multigenre responses to work by Fernando Pessoa, comes out in November 2021. A third novel, Re-Entry, or What Happened to Carlotta, is set for release in 2022. He teaches in the Department of Writing at the Pratt Institute.