Jack Hanson

Jack Hanson

In Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s third book, stories filled with the dreadful promises of pleasure and malaise.

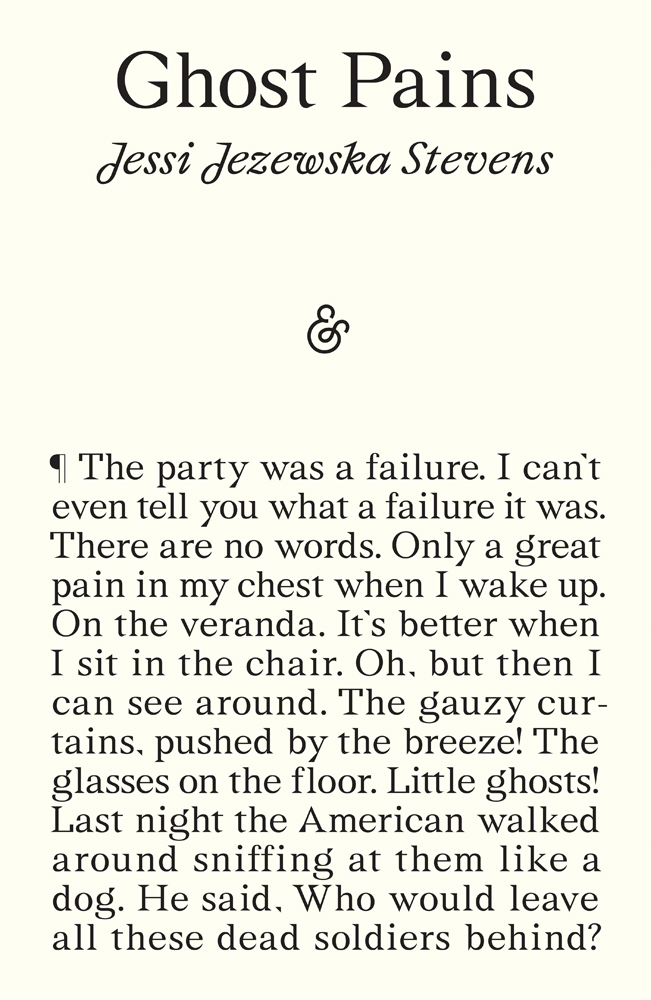

Ghost Pains, by Jessi Jezewska Stevens,

And Other Stories, 188 pages, $19.95

• • •

Introducing Tess Lewis’s translation of On the Marble Cliffs, Ernst Jünger’s metaphysical fable of impending apocalypse, Jessi Jezewska Stevens suggests the primary engine of that book’s power, as well as its driving insight, is the coincidence of deep internal contradictions and an elegant, even sumptuous exterior. It is a work of crystalline beauty, but beneath the narrative’s “icy polish” and the stillness of the fantastically rarefied world it describes, a frenzy of directionless violence awaits, free of constraining or clarifying principles and virtues, leading only to an abyss. In Ghost Pains, Stevens’s new collection of short stories, that subterranean chaos seems to have woven itself into the fabric of the quotidian, even at its most orderly and refined; the final reckoning may be forestalled, but the waiting itself has become the terror, the catastrophe of life just going on.

There are, of course, plenty of distractions, plenty of things with which to occupy oneself in this interminable meantime. In the opening story, the narrator, a character typical of Stevens’s work—an educated young woman, usually American, with little to do, preoccupied by a certain unnameable lack, about the contours of which she is nevertheless quite articulate—decides to throw a party. She does so while lounging around her Berlin apartment in lingerie she cannot afford, smoking cigarettes and considering the basil plant on her veranda, indications of a lifestyle that makes ample room for oscillating between indulgence and regret. Our protagonist seems at once utterly at home with herself and constantly compelled to offer explanations, even excuses: “I am a wraith, inhuman, alone in my room in chiffon hemmed with lace. I’m behind on my rent. Though it’s worth pointing out that while a robe costing one month’s habitation is an expensive robe indeed, rent in Berlin, if you know where to look, is extremely cheap.”

In a spasm of sociability, she emails an invitation around to “everyone I know,” including Ann, a friend to whom she has an ambiguous yet ardent attachment. Remembering her last soirée—a small one at which Ann had been present and which, owing to their inability to explain the nature of their relationship, “ended in disaster”—she decides to call the party off, but an unfortunate parapraxia intervenes: “Oh, the nuance of reply versus reply all! Not really so nuanced. Ann, the only guest to write back, was the only one to receive the cancellation.” Nuisances ensue; the grating self-regard of attractive guests and the persistent yelps of a dog from the street—which she insists sounds like human screaming—drive the narrator to the brink, and she closes out the evening with a laughing fit that clears the room, leaving her alone on the veranda, where she eventually falls asleep. Ann never shows—why would she?—and the silence of the morning seems to contain all the contradictory compulsions that led to the party in the first place. “I almost miss the screams,” the story concludes.

Malaise is a notable affect for Stevens, both as a writerly temperament and an object of exploration. The writing is undoubtedly colored by dissatisfaction, but it never reads as veiled confession, much less indulgence, being smart enough to draw out the pleasure the malcontent finds skittering over the surface of her gloom. The Exhibition of Persephone Q, Stevens’s 2020 debut novel, takes a certain delight in its fantastical-cum-pathological conceits, each having to do with the eponymous protagonist’s failure to recognize the world around her, and thus herself—a literary thrill that only enhances the real grief Stevens is able to evoke. Her sophomore outing, 2022’s The Visitors, emphasizes the comedy, foisting hallucinations of a conspiratorial garden gnome upon C, a broke and sexually frustrated burnout from the Occupy movement whose life has become wholly circumscribed by the anti-poetry of hyper-financialization. In both books, the humor is deep enough to coexist with the heartbreak; together, they form a life-affirming whole.

The stories in Ghost Pains are at once lighter on their feet and darker in their moods. The material is now largely the day-to-day of women living on the line between (or just on either side of) bourgeois privilege and lack thereof. The psychic terrain suggests a world threatening disintegration. Stevens writes: “What lies beneath a city? You could say rubble; you could say trash. Once upon a time the debris was piled and draped with dirt. Now we call them hills.” But the dirt is thinning out, and the trash is nearly visible again.

The fantastical that marks Stevens’s two novels has not entirely disappeared. In the most outwardly bizarre story, a computer geek, whose day job consists of insurance-tech dirty work (while accumulating astronomical sums in blockchain speculation on the side), makes a deal with a woodland imp: in exchange for helping the geek back into the computer game he’s been locked out of, the imp gets his next girlfriend. Outrageous though this central conceit may be, the conflicts and imagery seem to strain the border between the literal and the metaphorical, as if reality itself, being strange enough, balks at the strange-making.

Back in the realist world in which the other stories in Ghost Pains unfold, there is a flurry of activity, some of it quite agreeable, even as it is defined by absence. Sex is easy enough to come by, but desire, when it appears, is ambiguous and self-defeating. The language, though occasionally swept into lyric beauty, is more often stunted, gestural, a stubborn distance determining even the most involved first-person narratives. “For our honeymoon we went to Tuscany. This got a big sigh from me.”

In “Siberia,” a couple who once had an affair communicate by cell phone while under lockdown during a civil war. There is a frisson of knowing artificiality here, the characters talking as if the phones were a lamentable substitute for a real relationship, when in truth their physical separation is the only thing that makes their intimacy possible. This simulacrum of a connection is given a finer point when the narrative slips into script format, sometimes “He:” and “She:”; other times a cryptic metacommentary is offered from the representatives of the modern literary pantheon, each getting their cue as “Nabokov:”, “Chekhov:”, “Beckett:”.

There’s fun throughout Ghost Pains, but there is also an ambient dread that never quite goes away. The situation, in any case, is unsustainable. As with Jünger, it could be a variety of forces pressing the issue: he famously denied that the target of his allegory was Nazism alone, though others were happy to do so in his defense. There is even less etiological specificity in Stevens’s fictions, to her enormous credit. The point, which builds in clarity and intensity from a dizzying array of angles throughout the collection, seems rather that whatever these forces of destruction are, the ones that we begin to hear through the din of the party, the chatter at the bar, the static of the screen, they will not be content to go unnamed for much longer.

Jack Hanson is a writer, assistant editor at the Yale Review, and doctoral candidate in religious studies at Yale. His work has appeared in the Baffler, Commonweal, the Nation, and elsewhere. He lives in New York.