Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

In midtown Manhattan, public art meets public phones.

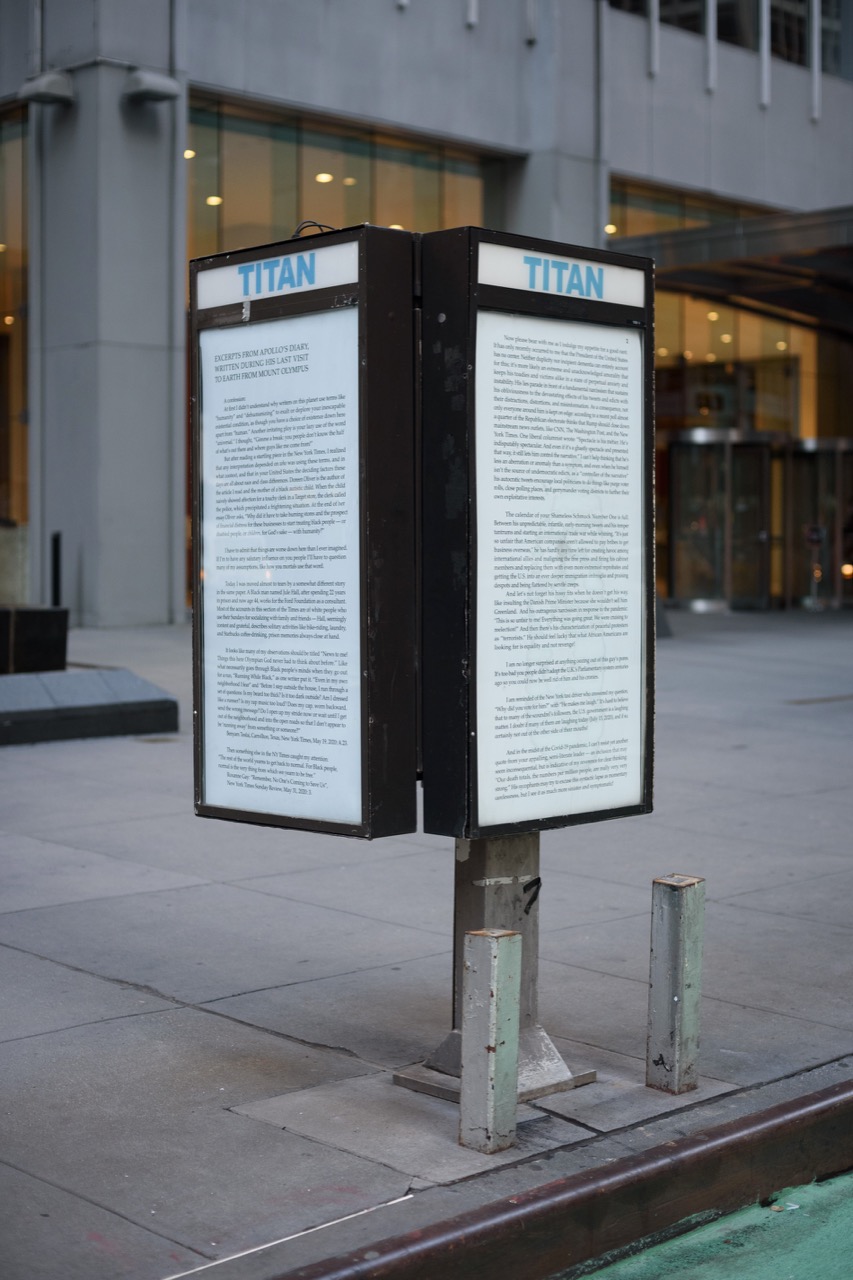

Installation view of Yvonne Rainer, EXCERPTS FROM APOLLO’S DIARY, WRITTEN DURING HIS LAST VISIT TO EARTH FROM MOUNT OLYMPUS, 2020, for TITAN. Image courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto. Photo: PJ Rountree.

TITAN, organized by Damián Ortega and Bree Zucker, presented by kurimanzutto, various locations on Sixth Avenue between West Fifty-First Street and Fifty-Sixth Street, New York City, through January 3, 2021

• • •

On the northwest corner of Fifty-Second Street and Sixth Avenue there is a long letter from the god Apollo flanking the sides of a Titan payphone kiosk: “Now please bear with me as I indulge my appetite for a good rant,” the missive begins, and away it goes. A couple blocks to the north, on the east side of the street, there’s a mirrored stall emblazoned with beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” Both declarations belong to TITAN, an exhibition organized by artist Damián Ortega and gallerist Bree Zucker, installed on twelve Titan phone booths spanning six blocks of midtown Manhattan. A provocative group show hung on a readymade structure, it is also a status report on possibilities for public art today.

Installation view of Cildo Meireles, Sermon on the Mount: Fiat Lux (1974–1979), for TITAN. Image courtesy the artist, kurimanzutto, Galerie Lelong & Co., and Galeria Luisa Strina. Photo: PJ Rountree.

The architecture that the curators have piggybacked on is important: the payphone is perhaps the last vestigial technology of the public sphere. Unlike the cell phone, the payphone brings communication to a standstill—and it doesn’t require investment upfront. In a privatized culture like ours it’s almost an embarrassment, refusing to go with the flow. Anachronistic, it belongs to another time yet is strangely still around. (These days, art feels a bit like that, too.) Most of the exhibition’s stalls are neglected and grody. They shelter Pure Leaf iced tea bottles, leftover halal chicken, half-consumed Prêt yogurts. One particularly busy station propped up a bike, a step stool, brooms, and housed two backpacks. COVID precautions aside, it was hard to imagine anyone wanting to pick up its crusty receiver, press it to one’s face, and chat with someone on the other end. The irony of the company’s commanding name and, by extension, the exhibition’s, could not be more spot on: the city plans to remove the kiosks next year.

Installation view of Patti Smith, It’s in our hands, 2020, for TITAN. Image courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto. Photo: PJ Rountree.

The less successful works in TITAN don’t get how neglected public space has become (the payphone is simply a metonym for its superannuation). Examples of capital-P public art, these interventions brim with the utopian possibility that often accompanies the idea of doing something outside. Equating the street with the public and the masses with politics, these artists seem to have forgotten that their contributions are unique one-offs rather than individual instances of larger campaigns. Patti Smith, for example, offers an encomium to democracy: a photograph of the word Vote written on a Caucasian palm, captioned It’s in our Hands, while Glenn Ligon delivers pictures of two neon sculptures spelling out November 3, 2020 and November 4, 2020, and a photograph of raised hands, promising a paradigm shift on Election Day. Rirkrit Tiravanija blithely encourages passersby to Remember in November. Hans Haacke’s contribution is more far-reaching—a poster he has used on many occasions, declaring, in many languages, We (All) Are the People, bordered by a color-wheel rainbow gradient. Anodyne agitprop, all of these messages struck me as repetitious, complacent, and familiar.

Installation view of Hans Haacke, Wir (alle) sind das Volk [We (all) are the people], 2003 / 2020, for TITAN. Image courtesy the artist, kurimanzutto, and Paula Cooper Gallery. Photo: PJ Rountree.

But these contributions make up only a third of the show. The best works meet the street in altogether surprising ways. Looking at oneself while reading Cildo Meireles’s mirrored blessings one can’t help but wonder whether or not one qualifies as the “meek who will inherit the earth.” Renée Green’s offering is equally steeped in doubt: After the Crisis and After You Finish Your Work, her signs read, and it’s hard to tell whether these sayings are excuses or promises. Rather than replicate advertising’s strategies in order to detourn them (as much critical art in the public sphere has done before), these artists realize that public space is no longer colonized by corporations but has been deserted by them, and that new opportunities might be available as a result. Minerva Cuevas’s works, memic amalgamations of text and image dropped into meatspace, come closest to the detourned formula, but they are so dry and funny that they turn into something else: You Don’t Hate Mondays / You Hate Capitalism, a gorilla says. Most Powerful Renewable Resource? / Denial. This from a lemur.

Installation view of Minerva Cuevas, Climate Change, 2020, for TITAN. Image courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto. Photo: PJ Rountree.

Walking through the exhibition, I recalled a few lines from Walter Benjamin’s 1928 One-Way Street. “Today the most real, the mercantile gaze into the heart of things is the advertisement,” the German critic claimed. “It abolishes the space where contemplation moved and all but hits us between the eyes with things as a car, growing in gigantic proportions, careens at us out of a film screen.” For many years Benjamin’s writing served as a charge to artists to commandeer technologies, such as advertising and film, that might have a massive and powerful effect. But the conditions of Benjamin’s modern metropolis no longer hold true. If the advertisement once dominated public space, today it thrives online—and more and more the street feels like leftover space. Junked and abandoned, it has been opened up for prophetic statements and queer looks, errant bodies and people with a sense of humor. Installed across from a forlorn Starbucks, Hal Fischer’s Gay Semiotics, a 1977 photographic primer on cruising fashion, evokes an era when cities were rife with all sorts of codes, looks, and meetups—and suggests, like a friendly ghost, that such covert operations might be reprised in the future.

Installation view of Hal Fischer, Street Fashion: Jock (from Gay Semiotics), 1977, for TITAN. Image courtesy the artist, kurimanzutto, and Project Native Informant. Photo: PJ Rountree.

As I walked up Sixth Avenue on a windswept Sunday morning taking pictures of old phones with my new phone (okay, it’s only an iPhone 7), the curatorial decision to install the exhibition in midtown as opposed to, say, Soho, seemed significant, because there are actually lots and lots of public sculptures on this stretch of Sixth Avenue. “Usually you’re offered places which have specific ideological connotations, from parks to corporate and public buildings,” Richard Serra told Douglas Crimp in a 1980 interview, explaining his decision to site an early sculpture in the Bronx. “It’s difficult to subvert those contexts. That’s why you have so many corporate baubles on Sixth Avenue.” Much of the work Serra describes is still there—and more of its type has been added. Jim Dine’s doubled Venus de Milos, installed in 1989, are permanently plopped down in a pool on the corner of Fifty-Third Street, while Scott Burton’s granite benches, ready to accommodate tired tourists since 1986, are tucked in a corporate plaza a block to the south. But TITAN, refreshingly, is neither monumental nor relational—at its best it takes you on a weird walk through one of the blanker corridors of the city. And, unlike Serra, it doesn’t seek to subvert power with big heroic gestures (all the bosses are working from home anyways), but rather finds a surprising path through the dereliction of public space.

Installation view of Yvonne Rainer, EXCERPTS FROM APOLLO’S DIARY, WRITTEN DURING HIS LAST VISIT TO EARTH FROM MOUNT OLYMPUS, 2020, for TITAN. Image courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto. Photo: PJ Rountree.

“I can’t help wondering what Walter [Benjamin] would have thought of the Rump era and the gloomy prospect that humans will have finally killed or consumed every last thing on Earth,” Yvonne Rainer, playing Apollo, muses in her fantastic contribution, which I almost got mowed down by an e-bike trying to read. “Even while heaving a doleful sigh, however, I must applaud all you survivors of trauma and cultural wars, hoarding your victories and counting your sores.” Yes, times are apocalypto-grade tough, but whoever trips over this little dérive of a show might get fresh, blessed, and delirious ideas about what to do in the cracks and crevices of New York’s grid, a place that feels so lifeless right now that it might, once again, be ripe with possibility.

Alex Kitnick is Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY.