Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

Falling in line with lines: a major retrospective of the

German-Venezuelan artist.

Gego: Measuring Infinity, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Gego: Measuring Infinity, curated by Pablo León de la Barra and Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through September 10, 2023

• • •

Infinity, obviously, cannot be measured. Or it can (see: Zeno’s paradox) but will be found boundless and infinitely divisible: any measurement of infinity will continue . . . to infinity (and . . . beyond?). For Gego—born Gertrud Goldschmidt, in 1912—the value was in the attempt. At the Guggenheim, four decades of her work, which has received greater recognition since her death in 1994, display the artist’s lifetime cross-disciplinary study, in her words, of “the infinity of three-dimensional geometry.” When asked in 1970 what was her creative approach to her work, Gego answered, “LINES IN SPACE.” The questionnaire followed up, “What is the starting point?” Ever laconic and reluctant to definitively interpret her open, experimental forms, which float like clouds of miasma, zigzag like transmissions, tangle like electrical accidents, she replied, simply: “LINES.” Lines, lines, more lines, and everything in between and around, over two hundred chronologically hung works stretch and spiral across mediums, a geometric sublime, through the curved eddies of the museum’s signature ramp.

Gego: Measuring Infinity, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Gego received a degree in architecture and engineering from the Technische Hochschule Stuttgart (now Universität Stuttgart) in 1938 and was urged, almost immediately, by one of her professors to hastily leave the country due to rising antisemitism. (Her family was part of the Jewish cultural and intellectual elite of Hamburg, where she shared a private tutor with the daughter of Max Warburg, brother of Aby.) Her parents secured visas for England, but Gego was denied residency there and instead immigrated alone to Venezuela. Completely unfamiliar with the language and culture of her new home, Gego nonetheless found employment at various city-planning studios and architectural firms in Caracas. She married and had two children with a fellow German (she was not the only exile scattered across the Americas), with whom she opened a lamp and furniture business, drawing, sketching, and painting on the side for pleasure.

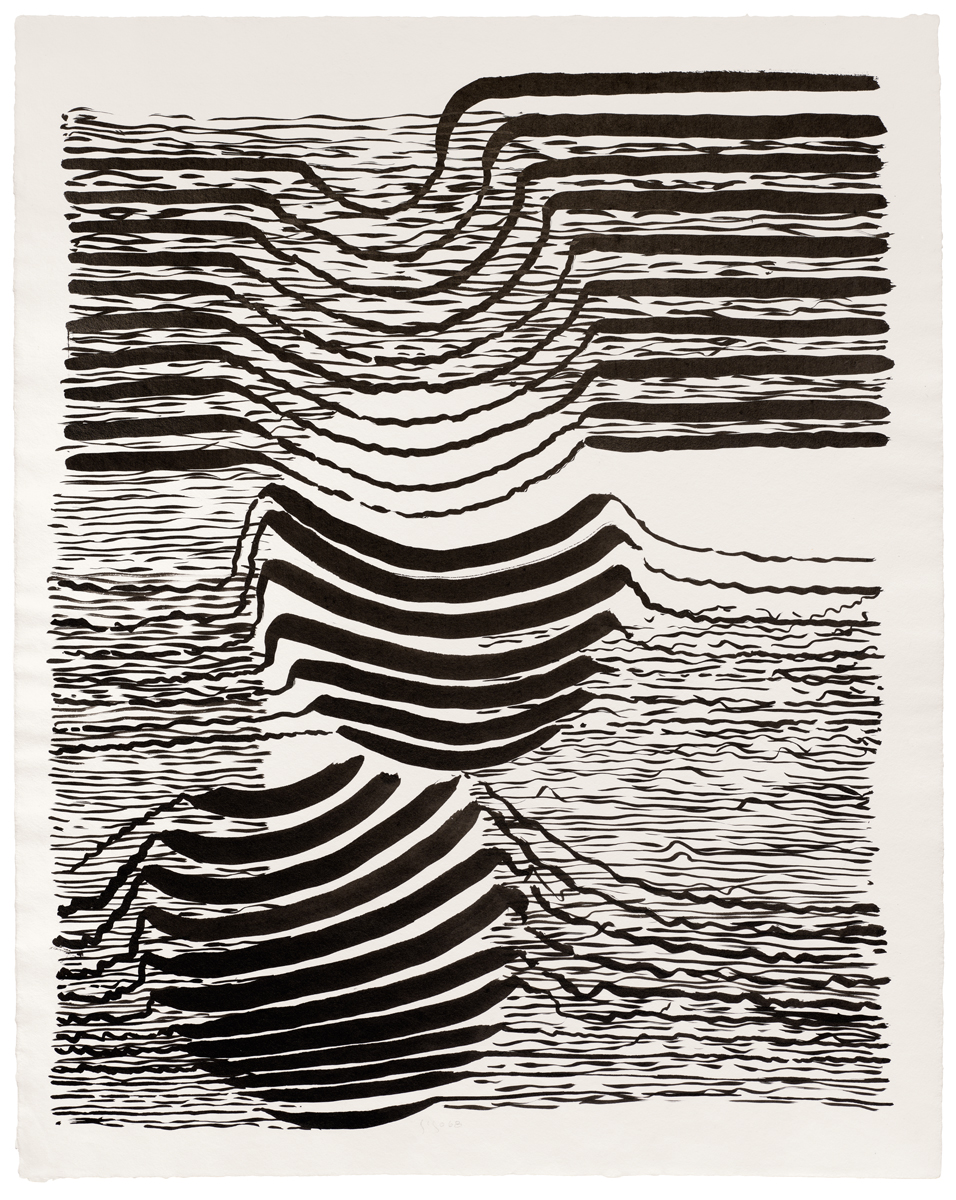

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Sin título (Untitled), 1968. Ink on paper, 24 7/16 × 19 3/8 inches. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo: Will Michels. © Fundación Gego.

Motherhood slowed her ambitions, but her children grew, and in the early 1950s, when she separated from her husband and met Lithuanian-born graphic designer and artist Gerd Leufert—who would be her lifelong partner—a sea change occurred in Gego’s art. Early watercolor and gouache works on paper and cardboard, bright landscapes of the coastal Venezuela where she and Leufert lived from 1953–56 before returning to the nation’s capital, quickly give way to dynamic angular drawings and prints, as if another visual world, spare and structural, has irradiated the surface of the everyday. The sharp palm fronds of local foliage and views of the rapidly modernizing sprawling metropolis seen from above are supplanted by gracile black lines that twist and slant, overlap and crisscross, intersect and turn in on themselves to form triangles, squares, rectangles, break off into stacks of parallel lines.

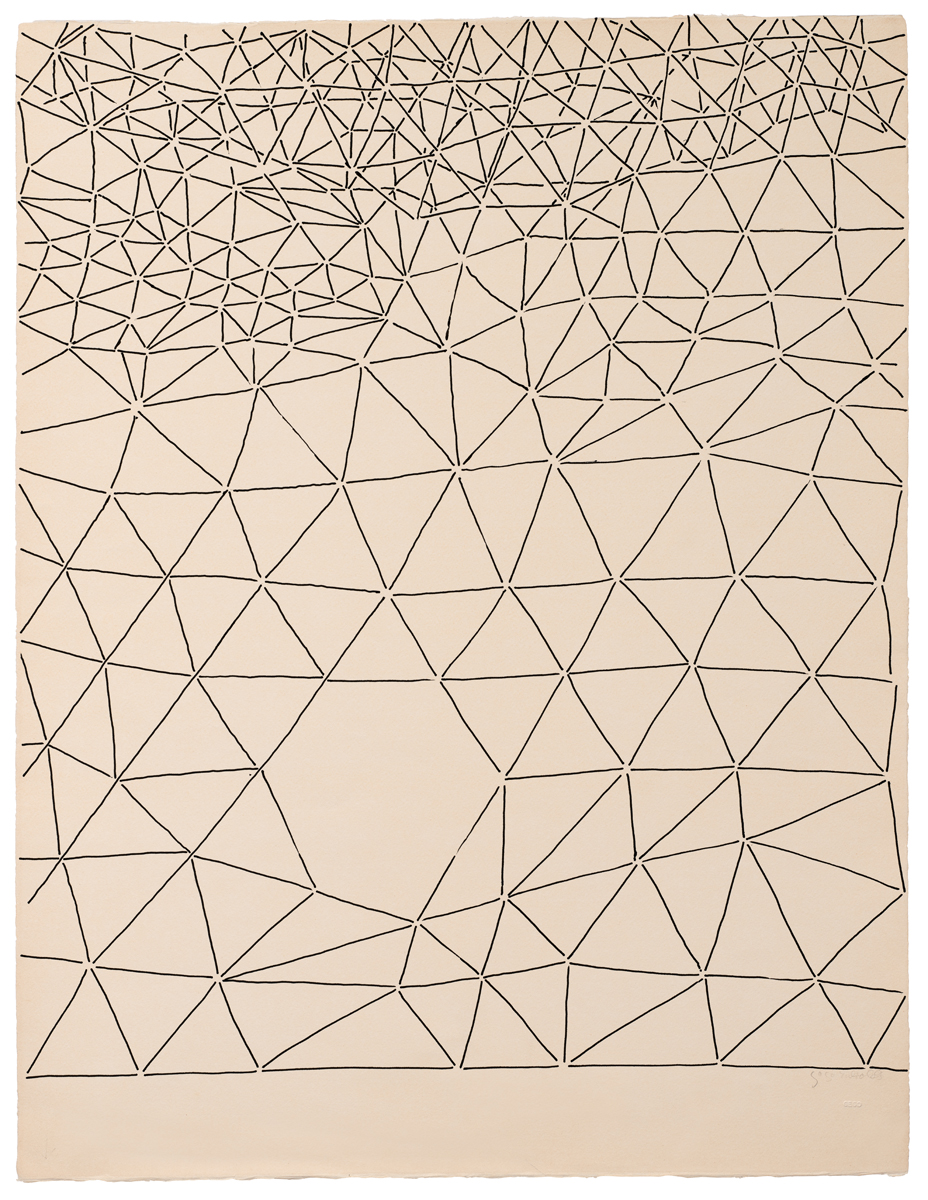

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Reticulárea, 1969. Ink on paper, 25 13/16 × 19 7/8 inches. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo: Will Michels. © Fundación Gego.

Neither diagrams nor models, these untitled nonrepresentative works nonetheless carve into the space of the blank page to imply three dimensions. As in one etching made in 1960 at the University of Iowa, where Leufert was briefly visiting faculty, Gego’s delicate striated forms appear solid but unmoored by gravity and uncontained by the edges of the page. In Movimiento dinámico (Dynamic Movement), a half-ovoid form turns at the center of the image like a tuning fork emitting disruptive waves into the surrounding thicket of lines. Similar patterns and motifs, though remarkably varied in texture and detail, continue in paper works of the late ’60s and find their plastic incarnation in iron sculptures painted in shades of white, black, and sometimes dark red. Modest in scale and displayed on low plinths, these works translate Gego’s graphic lines into sets of parallel rods that imply circles, triangles, and rectangles at once solid and transparent. Fixed to basic armatures, the rods overlap, darken, intensify, create new shapes depending on your vantage point.

Gego: Measuring Infinity, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

“Sculpture: Three dimensional forms of solid material,” Gego wrote in an undated note, “NEVER WHAT I DO!” In sculptural works, as in the drawings, light and dark, material and immaterial, are equally constituent parts, as if one could also climb a ladder using the void between the rungs. The artist was deeply invested in the ordered organization of volumes in space. (A manual made with her students at the pedagogically progressive Instituto de Diseño yields terminology not for the layperson: cuboctahedron, icosidodecahedron, rhombicosidodecahedron.) But she was equally compelled by the idea that “LINES” might be freed from geometry, to—at any point—disrupt and deform the regular. A series of smaller sculptures also made in the 1960s are wild, spiky forms fashioned from thin steel spokes manipulated into jagged, disorderly clusters, as if the line were in rebellion, ungovernable. (“You must . . . make it gauche,” Roland Barthes wrote of how to draw a line that is not stupid: “there is always a little gaucherie in intelligence.”)

Gego: Measuring Infinity, installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

“The net is life,” Gego said, and her Reticulárea—loosely, “area of nets”—sculptures made from the late ’60s through the ’80s could be seen as the epitome of the gauche, endlessly innovative line. Varied in scale (the first configuration, completed in 1969, occupied a whole room), these handmade nets of steel, iron, copper, and aluminum, sometimes with lead, bronze, plastic, and nylon fixtures, are modular structures composed of triangles, squares, parallelograms, or a combination of shapes. These installations are open, hanging literally like nets, while later related series are closed Columnas (columns), Troncos (trunks), Chorros (streams), and Esferas (spheres). These works were designed to be walked around and sometimes through (like the “penetrable” sculptures made by other Latin American artists of the time, such as Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Mira Schendel), an experience limply denied by the architecture of the Guggenheim. But one can dream. (“I’ve done it mentally for many years,” Gego said of her vision of hanging the Reticuláreas between skyscrapers, “they are dream projects, there is no need to make them reality.”)

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Bichito 87/14 (Small Bug 87/14), 1987. Plastic, iron, steel, and copper, 9 1/4 × 4 5/16 × 7 1/16 inches. Courtesy Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona. Photo: FotoGasull. © Fundación Gego.

Like much art of the postwar period, in Europe and the Americas, her work is influenced by the geometric abstraction of pre-war Modernist movements (Constructivist, Kinetic, Suprematist, De Stijl), and like many active in the 1960s, she turned from the hard edge of those styles. But in Gego’s wayward lines, which refuse the appearance of logic and coherence, one might also see a subtle critique of the aggressive oil industry–fueled modernization of Venezuela that left so many of its denizens in privation. Her fragile, precarious structures more closely resemble the organic world than the man-made: scrubland, underbrush, weeds, rhizomatic roots—that which endures, keeps growing and growing. In her later years, Gego made small, tangled sculptures from repurposed materials and discarded elements of earlier works—bichos and bichitos, she called them, terms that mean bug or critter but can also be employed to designate anything that doesn’t have a specific name. Something like the measure of infinity.

Emily LaBarge is a writer based in London. Her work has appeared in Artforum, Bookforum, the London Review of Books, the New York Times, and the Paris Review, among other publications. Dog Days will be published in the UK by Peninsula Press in 2024. An excerpt is in the winter 2023 issue of Granta, and another is forthcoming in the autumn 2023 issue of Mousse.