Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

In an exhibition of work by the late artist, eerie expanses of

song, sound, and voice.

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, installation view. Courtesy Raven Row. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff.

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, curated by Anthony Huberman, Raven Row,

56 Artillery Lane, London, through December 17, 2023

• • •

A room filled wall to wall with the softest, palest sand holds the imprints of all who have walked across it. Sneaker treads, heel pockmarks, and sweeping arcs are bathed in the light of a row of four television monitors that whisper enigmatic dialogue over a placid piano score, their screens flickering white like a malfunctioning shoreline: Tomas, what are you thinking? / I’m thinking how happy I am. Juliette Binoche and Daniel Day-Lewis right before they die in a car crash at the end of The Unbearable Lightness of Being. In another room, an electric Yamaha organ beneath a teepee of giant, precariously balanced tin pipes is played by robotic wooden mallets—a ghostly honky-tonk punctuated by the machinic clacking of depressed keys.

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, installation view. Courtesy Raven Row. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff. Pictured: Yamaha, 2010. Courtesy the Estate of Lutz Bacher and Galerie Buchholz.

The art of Lutz Bacher captivates with echoes, deferrals, and absences, including that of the American artist’s real name (never revealed, even after her death, at age seventy-five, in 2019, though it has been said her husband, the astrophysicist Donald C. Backer, was heard to call her Susan). At Raven Row, AYE!—titled for a Post-it note exhortation found in her archive—brings together a selection of works loosely grouped around the use of music, sound, and voice. Multimedia installations, videos, and sculptures from between 1997 and 2016 are sparely arranged across the gallery’s three floors. Sound is amplified (radios, giant speakers) and muffled (a depth of sand, a mountain of acoustic foam), moving images multiply and loop, voices borrowed and sampled are distorted, eerie, mesmeric—not so much speaking or singing as emoting, embodying, expanding. As Roland Barthes wrote, “is it not the truth of the voice to be hallucinated? Is not the entire space of the voice an infinite space?”

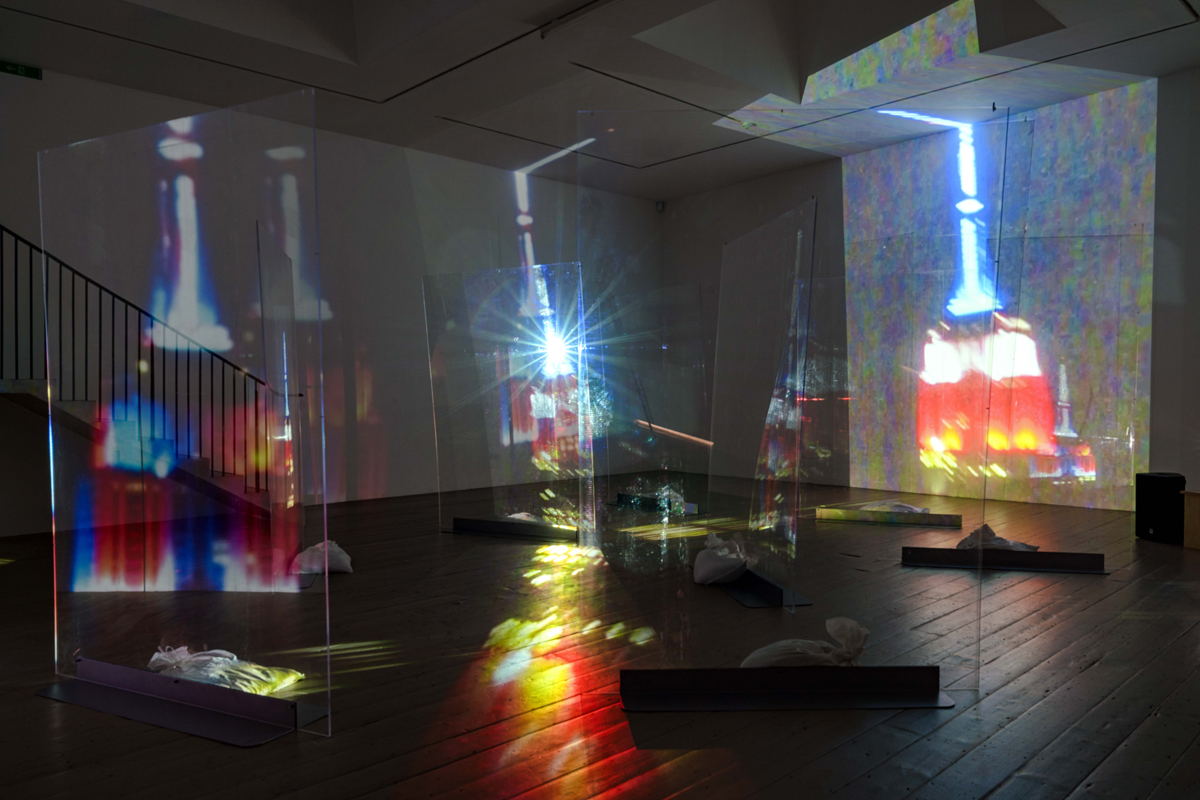

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, installation view. Courtesy Raven Row. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff. Pictured: Empire, 2014. Courtesy the Estate of Lutz Bacher and Galerie Buchholz.

Bacher’s work is often described as uncategorizable, unsettling, elusive, or—in her words—“one big ruin.” Her materials are unruly and wayward, at once wry and a little melancholy, assembled by the artist with a kind of rough conceptual magic. In Empire (2014), a two-channel video projects on opposite walls extended nighttime sequences of the Empire State Building, accompanied by an inchoate soundtrack of distant city noise. Its top tiers lit American red, white, and blue, the famous skyscraper is, in the grainy footage, unsteady, wobbling in the dark, as if the edifice were a source of uncertain comedy. In the middle of the gallery, several thin sheets of Plexiglas stand at different angles, fixed to the ground with metal frames buttressed by coarse sandbags. The emblematic protrusion of modernity, reflected and refracted by the flaccid transparencies, trembles and waves; the room spins like a neon cosmos when the camera pans across Gotham’s bright lights. Like Andy Warhol’s 1965 film of the same title, Bacher’s Empire reconstitutes time and space. But rather than assert its monumentality, here the notorious symbol of urban evolution is insubstantial, threatens to fold in on itself or collapse (as some might argue the Empire already has).

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, installation view. Courtesy Raven Row. Photo: Marcus J Leith. Pictured: Untitled (Diana), 1997. Courtesy the Estate of Lutz Bacher and Galerie Buchholz.

Another video, another collapse of empire: Untitled (Diana) (1997) is a single-channel projection of live footage from Princess Di’s funeral in September of that year. The camera is focused on the top of her coffin as it is borne down the checkered aisle of Westminster Abbey by solemn-faced pallbearers. Only a few minutes in length, the footage begins when the coffin, festooned with blooming tulips, roses, and lilies that sway with each forward step, enters the frame, and starts again, with a glitching stammer, when it has almost passed beyond. The church bells toll relentlessly in mourning, a reckoning that never ends, that becomes every moment of every day, scented with fluted white flowers that never die. An atmosphere, a texture, a mood fills the air, and some of the heart’s chambers.

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, installation view. Courtesy Raven Row. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff. Pictured: Please (LC), 2013–14. Courtesy the Estate of Lutz Bacher and Galerie Buchholz.

All art is relational, but in Bacher’s, it is as if a stop on the metonymic journey has been omitted. Her offerings are slight, their promises ambiguous and anarchic, but the more time you afford, the richer the dislocated reward. In PLEASE (LC) (2013–15), Leonard Cohen is projected in quadruple, a short visual with a soundbite from his 2008–2010 tour. His black fedora rakish against a luminous Klein-blue background, he says PLEASE, and please, he says, and PLEASE again, the accompanying chords overlaid in minor disharmony. PLEASE is a beseeching stutter, an imploring loop, a begging void, a technical difficulty, as his face kaleidoscopes through the space, immersing us in his blue longing. “Please,” Cohen says in so many of his songs, but this one is from “I’m Your Man,” his ballad of prostration: “And I’d howl at your beauty like a dog in heat / And I’d claw at your heart, and I’d tear at your sheet / I’d say please (please) / I’m your man.”

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, installation view. Courtesy Raven Row. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff. Pictured: KMS, 2016. Courtesy the Estate of Lutz Bacher and Galerie Buchholz.

KMS (2016) finds three radios playing a fragment of Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly” to each other with a slight delay, though each is picking up the same short-range pirate radio frequency. I stood waiting to hear from the modest Sony transistors how he sang that good song, how he killed her, me, us, softly, strumming our pain with his fingers. But the words never came; the epic bridge, with its crooning lament—ooooo-oh-oh-oh, wooah0ahoahoah, lalalaaaa-la-la-la—just kept wrapping around and around itself, around the room, an impossible skein: utterances on the edge of speech, never quite making it into syntax, grasping, reaching, soaring in that beautiful preverbal groove. This is the “grain,” perhaps, of which Barthes speaks, “the body in the singing voice, in the writing hand, in the performing limb.” The secret chord, maybe, that David played, and it pleased the Lord.

Lutz Bacher: AYE!, installation view. Courtesy Raven Row. Photo: Marcus J Leith. Pictured: Sweet Jesus, 2016. Courtesy the Estate of Lutz Bacher and Galerie Buchholz.

Outside, into the night, I could hear Sweet Jesus (2016) through the gallery’s open window: the Gospel of Matthew read in the deepened, slowed-down voice of James Earl Jones, a legacy of fathers and sons, man begetting man begetting the Messiah. The litany faded behind me, past a busker singing “Don’t Worry, Be Happy”—an impossible demand in this world. Please, please, please, I thought, walking in time with Cohen and his pleading progenitor James Brown, whose “Please, Please, Please” is proffered no fewer than seventy-five times before he falls to his knees and must be helped offstage. Please (please), I thought, unsure as to what for, but in the song, it’s anything and everything, isn’t it? An infinite, hallucinatory space.

Emily LaBarge is a writer based in London. Her work has appeared in Artforum, Bookforum, the London Review of Books, the New York Times, and the Paris Review, among other publications. Dog Days will be published in the UK by Peninsula Press in 2024. Excerpts appeared in the winter 2023 issue of Granta and the autumn 2023 issue of Mousse.