Megan Milks

Megan Milks

A new novel by Henry Hoke captures and sets free the emotional inner life of P-22, the famed LA mountain lion.

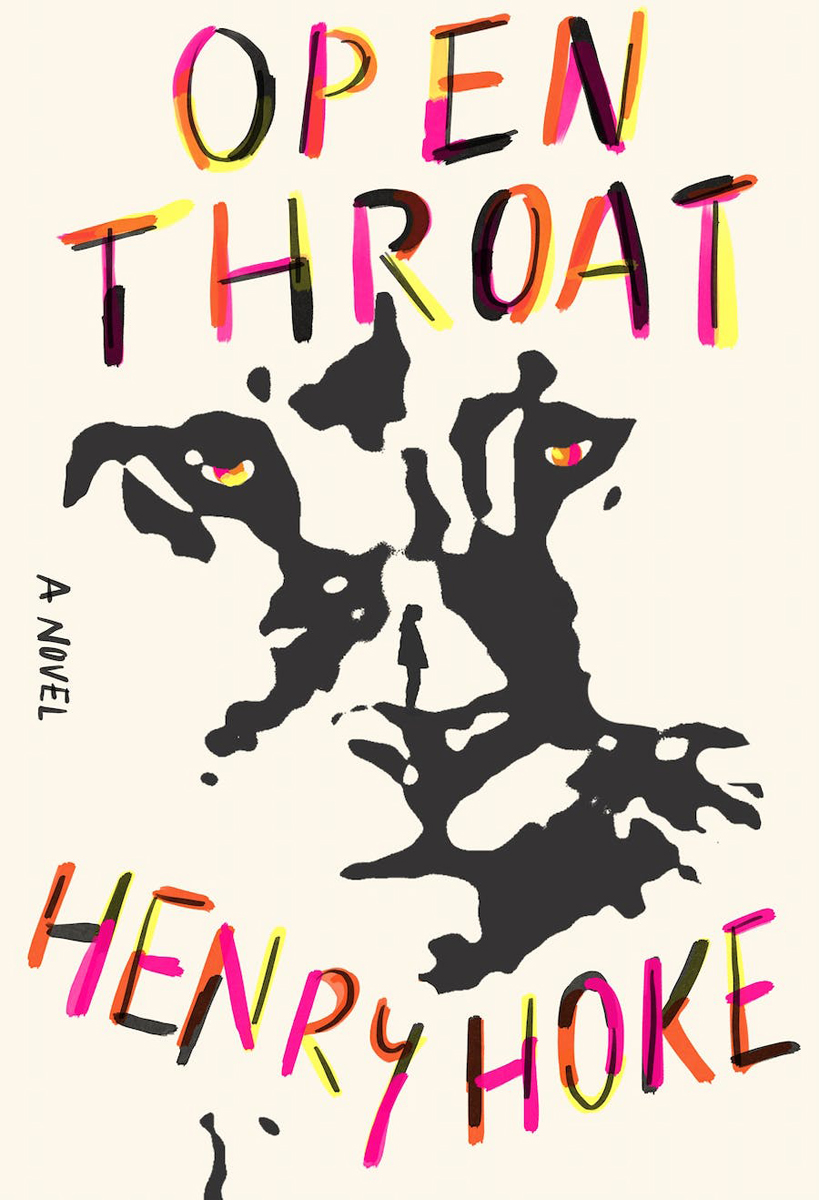

Open Throat, by Henry Hoke, MCD, 160 pages, $25

• • •

Beloved puma P-22 captured the public’s attention as soon as he was discovered in LA’s Griffith Park in 2012. To get there, he had survived crossing two major freeways—a deadly gauntlet that has claimed numerous big cats, and which would now forever separate him from his kind. He forged his way in the human world alone, making headlines by lounging in a Los Feliz crawl space for several hours and possibly (probably) eating a koala at the Los Angeles Zoo. Within a year, P-22 had gone viral thanks to a National Geographic photograph of him sauntering in front of the Hollywood sign, and his celebrity was powerful: when he got sick from a poisoned rat, his case helped to prompt a state ban of several rodenticides; he was the unwitting mascot of a successful campaign for a wildlife crossing over the infamous Route 101. He resided in Griffith Park until the end of his long and remarkable life in 2022.

As the real-life puma’s story poignantly illustrates, humankind’s inexorable sprawl is leaving the wild with nowhere to go but toward us; Henry Hoke’s new novel, Open Throat, is about this struggle to coexist, reconfiguring P-22’s biography into a tightly compressed timeline embellished with invented scenes. When we first meet our sharply observant, curious, philosophical, often melancholy feline protagonist, they’re in a thicket watching three humans (actors?) fool around with a whip, and they are contemplating opening a throat—the whip-wielder’s thick neck is particularly enticing. (I’m using “they” pronouns for this unnamed narrator to match those adopted in the publisher’s summary of the book. Sexed male, the lion is gendered “she” by Jane, a human ally they meet later; they do not comment on their own gender.) They don’t attack, but it’s an option they consider repeatedly as their food options dwindle. Over a series of short episodes, we are with our narrator as they survive an earthquake, hunt bats, and interact (from a comfortable distance) with “their people,” who live in a tent camp in the park. When two men set fire to the camp in a deliberate act of malice against this unhoused community, the puma jumps into action, to no avail. The fire’s spread displaces the lion and sets into motion the events of the rest of the novel, which nod at P-22’s journey while taking major departures.

Hoke’s fifth book, Open Throat fits in easily with the prose-poetry leanings of much of his previous work, such as the hybrid collection The Book of Endless Sleepovers (2016) and the recursive novel The Groundhog Forever (2021). Composed in floating sentences without periods or standard capitalization, the fragmented prose of Open Throat approaches the quality of verse. “I think I’m kind of a poet,” the lion tells us after overhearing a hiker say something similar. And they are: parade confetti is “pinks and reds like sparks of blood and thought”; the interstate is “the long death.” Having received so many words from listening to passing hikers, they have come to understand much common English and a bit of Spanish. The lion is always learning; they pick up “fucking helicopters” from a human and later deploy it in a metaphorical register to describe the blades of hedge clippers, a term they don’t yet have. “in my head it’s all people language,” they say. But in many ways, language is also a big problem for this cat; if the book’s title signals violence, it also suggests vocalization, and their inability to speak frustrates cross-species understanding. “someday I’ll be able to write what you’re reading,” they tell us, paradoxically. “maybe . . . on the other side of the world from the burning hills / in new york with a therapist . . . / or maybe it won’t ever get written / only growled.” Hungry for the next kill, the cougar is also hungry for connection.

The cat’s struggle to communicate also prompts some capricious linguistic choices on Hoke’s part. LA is consistently transliterated as “ellay”; Disney as “diznee.” These are cute, I guess. Hoke is using such phonic renderings to wink at the reader and acknowledge the artifice of the perspectival conceit. But why would literally every other word be written with conformity to “correct” English-language spellings? If “scare city,” why not “tore meant”? If “ellay,” why “santa fey” and not “santa fay”? (Does the lion know the word “fey”?) I found myself distractingly fixated on these questions. (For this, I blame Yoko Tawada’s 2011 Memoirs of a Polar Bear, and the playful rigor with which it makes sense of itself as a written text.)

That these precious-seeming alternate spellings threw me out is perhaps testament to how otherwise persuasive Hoke’s emotionally immersive construction of this lion mind is—and that is the book’s great achievement. Even more so than with the character’s wry, befuddled observations about us, I was caught up in the wild world of feeling and desire that Hoke has conjured. Especially captivating is the lion’s recounting of their short-lived companionship with another lion they call the “kill sharer”: “I treasured the way he blew air out of his nostrils / no deer lasts as long as you want it to.”

This slim, compulsively readable story doesn’t last long enough, either. But what options really exist for a mountain lion wandering LA? Though Hoke takes some bold swoops through fiction and fantasy, he doesn’t alter this unhappy reality. The novel’s collision of the human and animal worlds incites amusing incongruities and heartwarming exchanges—teenaged Jane hides the cat in her room, supplying them with raw ground meat (“shredded goo,” as they put it) and a litter box—but the interrelationship can only be tenuous and brief.

P-22 was euthanized late last year after park rangers, noticing his erratic behavior, captured him for a medical examination that revealed injuries consistent with a vehicle accident. While the book was not written as a memorial—P-22 was still alive when it sold—its sentiment is suffused with grief, for these animals whose shrinking habitats cannot support them, for the impact of climate change, for a world on fire. In bringing P-22’s memory into literary fiction, Hoke has provided us with a space to mourn and connect, at least with an imagined version of this iconic cat. Hoke’s lion may be human-made and human-ish, but Open Throat holds and honors their forerunner’s wildness.

Megan Milks is the author of the novel Margaret and the Mystery of the Missing Body, finalist for a 2022 Lambda Literary Award, and Slug and Other Stories, both published by Feminist Press.