Albert Mobilio

Albert Mobilio

A centennial showcase of the mid-twentieth-century street photographer’s distinctive eye for the intimate, abstract, and impressionistic.

Centennial: Saul Leiter, installation view. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery. Photo: Clark Mizono.

Centennial: Saul Leiter, Howard Greenberg Gallery, 41 East Fifty-Seventh Street, Suite 801, New York City, through February 10, 2024

• • •

A city might be defined as a place whose inhabitants live in public. Whether on the sidewalk, square, or subway, we are available to be watched and scrutinized; even in our apartments, we can be spied out from the avenues, our shadows moving behind curtains. A generation of street photographers—Lee Friedlander, Helen Levitt, Garry Winogrand, and Weegee among them—made New York City their open-air studio, one in which they relied on those moments of spontaneous revelation the town so freely disburses. Saul Leiter roamed the same streets during the same period as these photographers and bore a similar affection for the city’s ongoing spectacle. But when he died in 2013, he had just begun to be recognized as their peer. The release of a documentary film—In No Great Hurry: 13 Lessons in Life with Saul Leiter—that year and the subsequent publication of several volumes of photos advanced his reputation while also revealing his pronounced distinctiveness from the pack. Despite street photography’s necessarily offhand, voyeuristic method, the photos produced by its luminaries often have a studied quality. Exhibiting a classical composition and social narrative, Winogrand’s New York World’s Fair (1964), with its row of variously animated women on a park bench, is justly iconic, an image ready-made for the museum postcard rack. Leiter, on the other hand, creates impressionistic effects that often obscure his subject—ones that are often themselves obscure. He is a poet of the interior world of public space.

Saul Leiter, Taxi, 1957. © Saul Leiter Foundation.

At Howard Greenberg Gallery, a show marking Leiter’s centennial offers a range of his work over several decades—street photography, fashion images for Harper’s Bazaar, moody chiaroscuro nudes, and paintings bearing kinship with assorted Abstract Expressionists. In each of these categories, most especially street photography, Leiter proves an ingenious craftsman whose skill resides in cloaking a wry subversiveness within seeming naivete. His artistry doesn’t announce itself. Perhaps this is why it took many years, and his passing, for him to gain deserved recognition. And, of course, there was his own disinclination toward careerism: in 13 Lessons in Life, he repeatedly expresses dismay at being its subject. “I’m not carried away by the greatness of Mr. Leiter,” he tells director Tomas Leach.

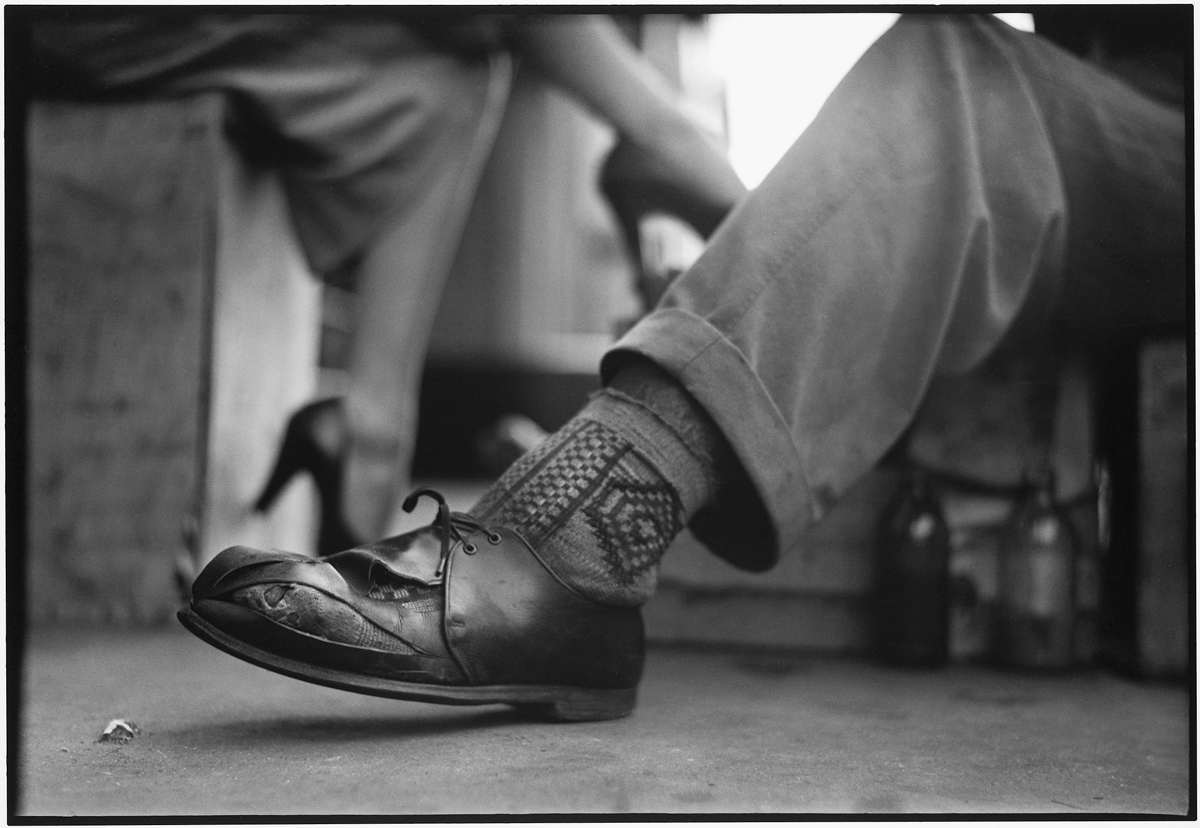

Saul Leiter, Shoes of the Shoeshine Man, ca. 1951. Gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1970, 8 × 10 inches. © Saul Leiter Foundation.

A series of black-and-white photos titled Shoes of the Shoeshine Man, published in Life in 1951, offers only that: images of the tattered footwear that shod the men waiting to polish the shoes of others. But the implied social hierarchies, while present, recede within Leiter’s formalist approach, and the images take on an abstract, taxonomic quality that might call to mind the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Unlike their photos of sizable structures, though, Leiter’s pictures deliver viewers to the unnoticed, even disdained realm of pavement level. This is where intimate things—a torn sole, frayed cuff, bare ankle—usually evade notice. Although no face is in sight, Leiter’s voyeuristic intrusion cuts especially sharp.

Saul Leiter, Pull, ca. 1960. Chromogenic print, printed later, 20 × 16 inches. © Saul Leiter Foundation.

Foul weather suited Leiter’s desire for subjects who, rather than conversing on park benches, are burdened with heavy coats and hats, darting amid snowfall or a downpour. “There’s something about raindrops,” he says in the film, and he often allows the precipitation to blur his lens, or he shoots through splattered glass. The color print Pull (ca. 1960) depicts two figures, a woman and a man, visible through a streaked and foggy glass door (a “pull” sticker dominates the foreground). Standing in slush, their bodies are charcoal smudges that appear to deliquesce in the condensation. They inhabit an otherworldly, ever-decomposing zone rather than some familiar New York scene.

Saul Leiter, Red Umbrella, 1958. Chromogenic print, printed later, 20 × 16 inches. © Saul Leiter Foundation.

Leiter began using color in the ’50s, when it was dismissed by critics as not serious. He employed its eloquent possibilities in sly, unexpected ways. In another winter scene, a woman makes her way through billowing flakes, her red umbrella daubed with white. Her posture suggests she was moving quickly through the storm. We might imagine that Leiter was aiming to capture the cryptic graffiti on the facade behind her when she darted into his viewfinder. The umbrella arrives in this gray tableau as if by accident, its hue a quiet eruption. Red Umbrella (1958) displays a quintessential urban encounter—a swath of empty, anonymous space pierced by a random passerby, one glimpsed partially and then, by implication, only for a second. Leiter isn’t looking for Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment,” but rather those moments that elude us even as we experience them.

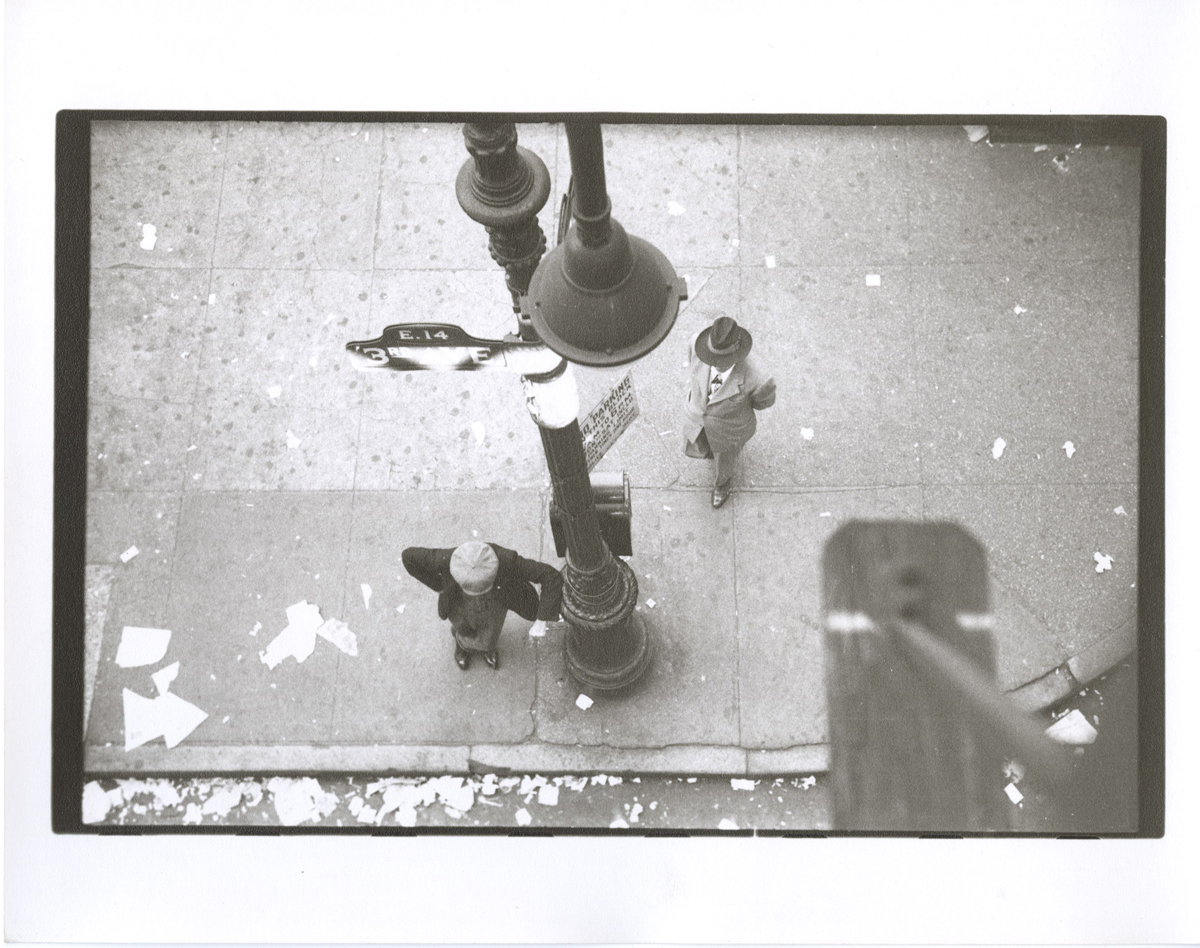

Saul Leiter, From the El, 1950s. © Saul Leiter Foundation.

The occluded or atypical perspective is surely Leiter’s trademark. He shoots people from inside moving cars, reflected in mirrored surfaces, or observed from beneath a canopy. A crowd of tourists jostle at the rear of a San Francisco cable car in an untitled shot taken from the backseat of a taxi through its windshield. Or we inspect street scenes from elevated perches, the camera’s field blocked by subway trestles or window gates, the subjects arrayed like anthropological specimens below. One shot in the series From the El (1950s) presents two men from directly above, their faces invisible beneath hats, next to a bishop’s-crook lamppost; the arching light looms over these mere acolytes to a vertical master. Leiter works against compositional conventions to achieve a visual equivalent of storytelling’s in medias res, a sense that the before and after of what the camera has recorded is of equal and perhaps greater importance.

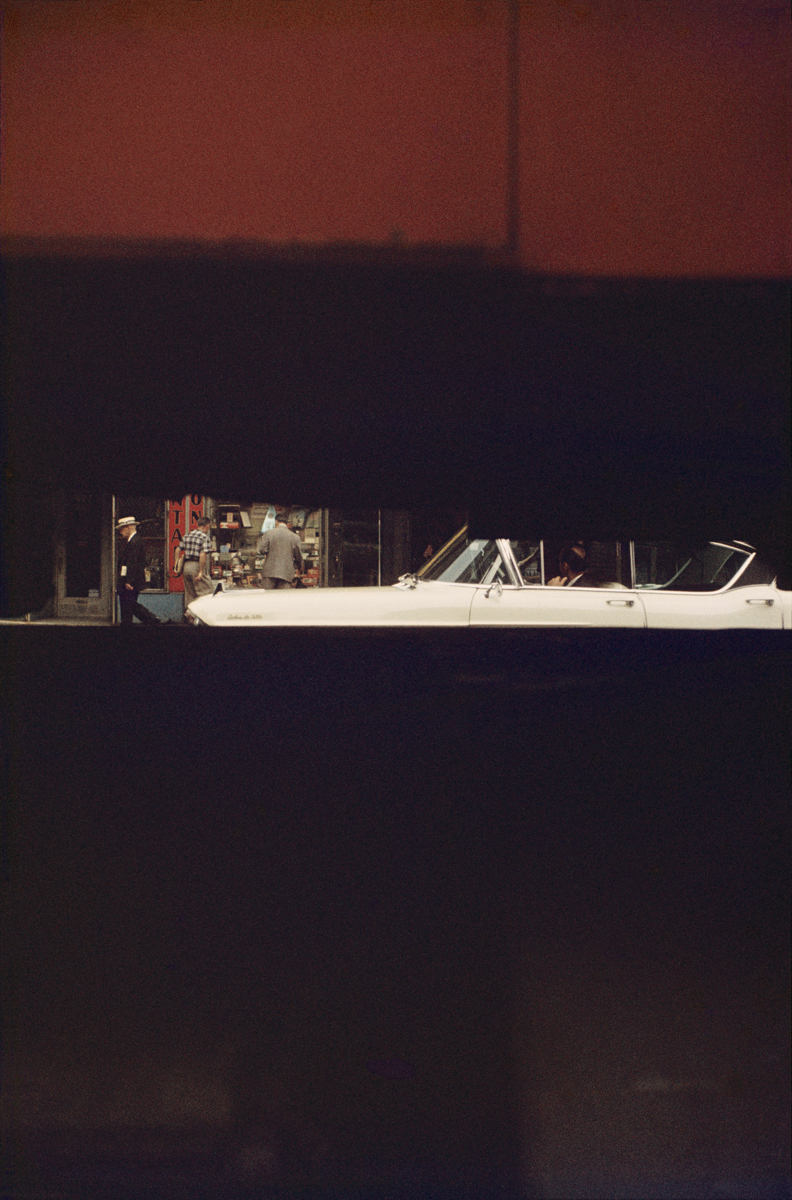

Saul Leiter, Through Boards, 1957. © Saul Leiter Foundation.

Photography’s uneasy relationship to verisimilitude has been broadly understood since well before the era of digital manipulation, yet we still continue to believe in the rough equivalence of photos to facts. Leiter questioned this connection with images that prize what can’t be known, his camera often entering a scene veiled or at an oblique angle so as to register the mechanism’s inadequacies. Through Boards (1957) is candid about this choice. (Unfortunately, it is not in the exhibition, but can be found in the thorough new monograph Saul Leiter: The Centennial Retrospective.) The shot was taken behind planks, perhaps from within a construction site, that blind us to all but a lustrous sliver in the center of the frame, where a shiny white automobile appears to be parked and pedestrians regard a shop window. The bottom half of the photo is almost completely black, while the top consists of two bands, one black, one rust-colored; between these Rothko-like striations lies the slender domain of lived life, its fullness withheld from us, fleeting in this unknowing. This is Leiter’s unheard melody. “The real world,” he confides in the documentary, “has more to do with what’s hidden.” The paradox—that an instrument dependent on light might serve the goal of concealment—is only one of the many satisfying provocations afforded by this retrospective.

Albert Mobilio is the author of four books of poetry: Same Faces (2020), Touch Wood (2011), Me with Animal Towering (2002), and The Geographics (1995). A book of fiction, Games and Stunts, appeared in 2016. He was a MacDowell Fellow in 2015 and awarded an Andy Warhol Arts Writers Grant in 2017. A former editor at Bookforum, he is currently an editor at Hyperallergic and an associate professor of literary studies at Eugene Lang College at the New School.