Michelle Orange

Michelle Orange

In Bob Fosse’s Weimar-era fable, style meets fascism (and Liza Minnelli).

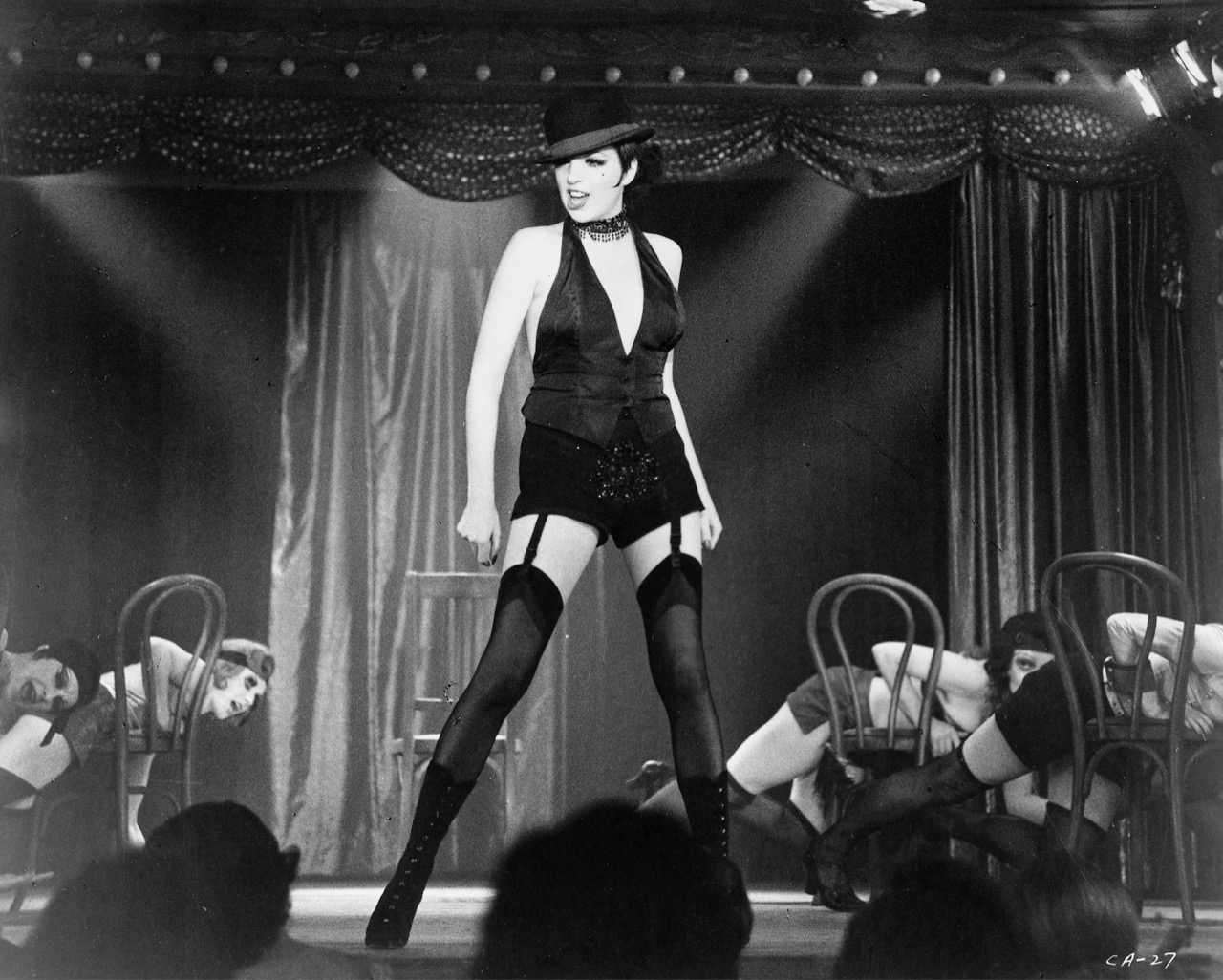

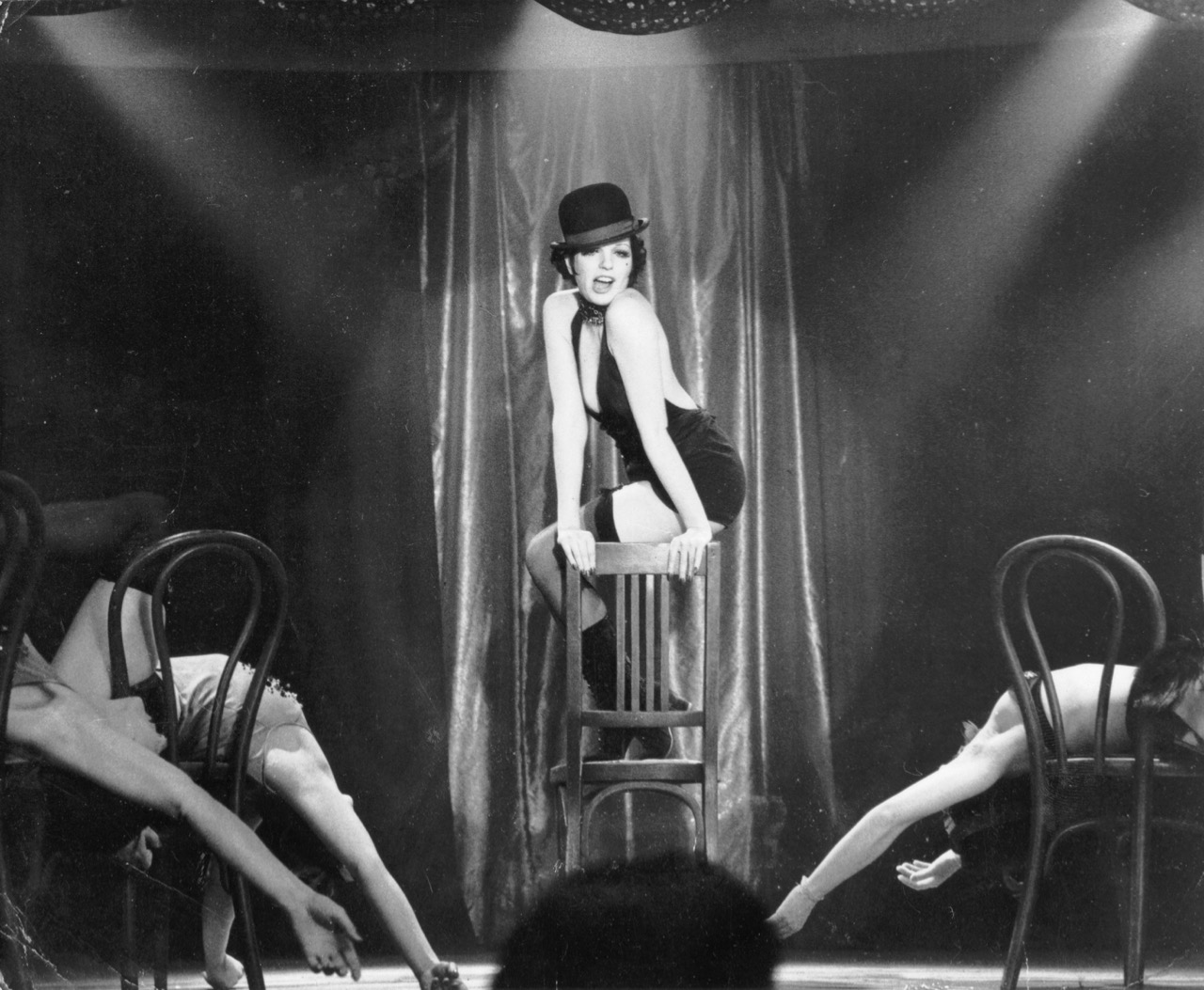

Liza Minnelli as Sally Bowles in Cabaret. Image courtesy Getty Images. Photo: Silver Screen Collection.

Cabaret, directed by Bob Fosse, available to buy or rent on all major streaming platforms

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that movie theaters in New York City, where 4Columns is based, and other cities throughout the US remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

I was no longer new to the United States when I first watched Cabaret (1972), though a sinuous national unfurling had ensured, year by year, that my adopted home remained new to me. Early on, most of the things I loved about living as an American—specifically a New Yorker—were local, low-stakes discoveries: bodega culture, Saturday mail delivery, open curiosity between strangers. Much else, it seems to me now, took real effort not to know going in. Self-exile is so often driven less by a clear sense of where one is headed than what needs leaving behind. Yet on some level I understood the bargain, that America’s attractions—its porousness, dynamism, scorn for limits and worship of style—contained seeds of its menace.

Having avoided the film on the half-conscious hunch that a right time and place would come, I rented Cabaret at some point during the first Obama administration, in the midst of an acute Bob Fosse phase. I don’t recall the spark that set me chasing Fosse through the bowels of YouTube, only the discovery’s consoling, salutary effects. First a dancer, then a choreographer and stage and screen director, Fosse often described his success as emerging from a sense of lack: to hide his balding head, bad posture, and poor turnout, the man who longed to be Fred Astaire developed steps that featured hat work, rounded shoulders, and turned-in feet. The fixes bore out a larger vision, one that gave form to a modern shift toward heightened modes of self-consciousness, irony, and decadence. Fosse’s bodies could not just hold two opposing ideas—eroticism and detachment, beauty and monstrosity, vitality and decay—but make them dance.

I felt myself a failed American in those years, scrambling from visa to visa, crushed by the recession, relieved by Obama’s election yet unmoved by his rhetoric. Disillusion is central to the immigrant experience: US transplants especially spend years parsing their truly egregious oversights from those they couldn’t have foreseen. For me that process converged with a crisis of social disunion so dizzying even native citizens struggled to take it in. Fosse’s work seemed to capture and set to rhythm something of the country’s essential duality, a dilemma just then entering its late stage. Clicking through decades-old clips of Fosse-choreographed numbers in Hollywood musicals The Pajama Game, Damn Yankees, and Kiss Me Kate, I recognized in each splendid, deconstructed combination a working out of the American riddle whose volatility I had come to appreciate more each day.

Joel Grey as the MC (center) and cast in Cabaret. Image courtesy Getty Images. Photo: John Springer Collection.

Framed as a star vehicle for Liza Minnelli, Cabaret was also a comeback for Fosse, whose film directing debut, the 1969 screen adaptation of the musical Sweet Charity, had fallen flat. Also based on a Broadway show, Cabaret lifted and embellished elements from Christopher Isherwood’s writing about his time in early 1930s Germany. The British author’s Berlin Stories (1945) had previously inspired the 1951 play I Am a Camera; in the 1955 film adaptation, a growling, elfin Julie Harris reprises her stage role as the feckless, gold-digging, expat nightclub singer Sally Bowles. Though they range considerably in tone, plot, and approach, each stage and film version emphasizes the contrast between a bohemian love story and its backdrop of poverty, political hatred, and despair, a city “profoundly indifferent,” Isherwood writes, to the rise of the Nazi party. A fatal mix of cynicism and credulity, his Berliners treat politics as the new diversion, conspiracy theories and party meetings being “cheaper than going to the movies or getting drunk.”

Liza Minnelli as Sally Bowles and Joel Grey as the MC in Cabaret. Image courtesy Getty Images. Photo: Silver Screen Collection.

I was an instant convert to Fosse’s Cabaret: it was and is nothing but the movie for me. If his work is often described using double-edged terms like stylish, Cabaret concentrates Fosse’s interest in stories about style—its power to define and transform, to dominate and subdue. His uniquely American sensibility found its most indelible expression in a Weimar-era fable that probes the relationship between fascism and bourgeois entertainment. Harold Prince’s 1966 Broadway production introduced a slate of wry, ridiculously tuneful John Kander and Fred Ebb songs and the addition of a Master of Ceremonies, played by Joel Grey (who plays the same role in the film). A freaky, Depression-era clown with bad taste and feel-good energy, the MC morphs, as the story progresses, from common applause-whore to consummate evil. Fosse’s agile pacing and prolific cross-cutting intermingle the hidden, wildly aestheticized world of the Kit Kat Klub—where Grey and Minnelli’s Sally Bowles perform lewd, up-tempo numbers for alternately bored and titillated upper-crust clientele—and that just beyond it, in which Sally seduces her adorable, inscrutable roommate Brian (Michael York), paints her nails a “shocking” emerald green, and maintains near-complete ignorance of the encroaching Nazi threat.

Michael York as Brian and Liza Minnelli as Sally Bowles in Cabaret. Image courtesy Getty Images. Photo: ABC Photo Archives.

“You know, you’re really very good,” Brian tells Sally after she rips through a swirling rendition of “Mein Herr.” “I know, darling,” she replies. “Isn’t it fabelhaft?” It is. Turns out I have no patience for the notion that a legit Sally Bowles must sing badly, per Isherwood’s passing description. Watching the 2014 Broadway revival, in which Michelle Williams joined the league of those who would mangle excellent showtunes in the name of authenticity, only left me longing for the film. That my astonishment grows with each return to it owes in large part to Minnelli, whose hold on the viewer is too complete to be comfortable. Her bravura displays of talent deepen that bind, dazzling audiences in much the same way Sally’s pursuit of epic singularity has blinded her.

Liza Minnelli as Sally Bowles in Cabaret. Image courtesy Getty Images. Photo: Ullstein Bild.

Across a decade of watching Cabaret, Sally’s supreme devotion to style has struck me in different ways. Over time I have noticed how critical her absence is to the sequence in which a blond teenager, framed in close-up, begins to sing at a countryside beer garden. “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” opens as a pastoral ode to the Fatherland’s warm meadows and forest stags, but as the song builds and more gleaming-eyed patrons stand to join in, the scene is transformed. The young man is revealed to be in full Nazi regalia, a costume and stance as finely crafted as his anthem. “The logical result of fascism,” Walter Benjamin wrote shortly after fleeing Germany in 1932, “is the introduction of aesthetics into political life,” an emphasis on spectacle that allows the disaffected to express themselves while preserving the reigning power structure. If nothing else, Sally and the Hitler Youth share a most serious interest in self-invention, design as destiny, the infinite promise of a well-cut suit.

A recent viewing left “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” burrowed deep in my mind. I caught myself humming it through the ordinary hours of which even extraordinary times are made—in the shower, making lunch, out with the dog. An unwelcome reminder of what even a half-decent song can do.

Michelle Orange is the author of This Is Running for Your Life: Essays and the forthcoming nonfiction book Pure Flame.