Nick Pinkerton

Nick Pinkerton

How many Wes Anderson films can fit into a Wes Anderson film?

Jake Ryan as Woodrow Steenbeck, Jason Schwartzman as Augie Steenbeck, and Tom Hanks as Stanley Zak in Asteroid City. Courtesy Pop. 87 Productions / Focus Features.

Asteroid City, directed by Wes Anderson, now playing in theaters in New York and Los Angeles, opens nationwide June 23, 2023

• • •

Wes Anderson’s precise, symmetrical, planimetric compositions, the most readily identifiable hallmark of his cinema, can be traced to the filmmaker’s passion for the theatrical—per actor Jeffrey Wright, one of many Anderson veterans returning to the fold for Asteroid City, the director uses his frame as “a kind of cinematic proscenium.” Theatricals, amateur and otherwise, abound in Anderson’s films: Max Fischer’s productions in Rushmore (1998) and Margot Tenenbaum’s in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001); the role played by Benjamin Britten’s Noye’s Fludde in Moonrise Kingdom (2012); and the Knoblock Theatre staging that ends the “Revisions to a Manifesto” section of The French Dispatch (2021).

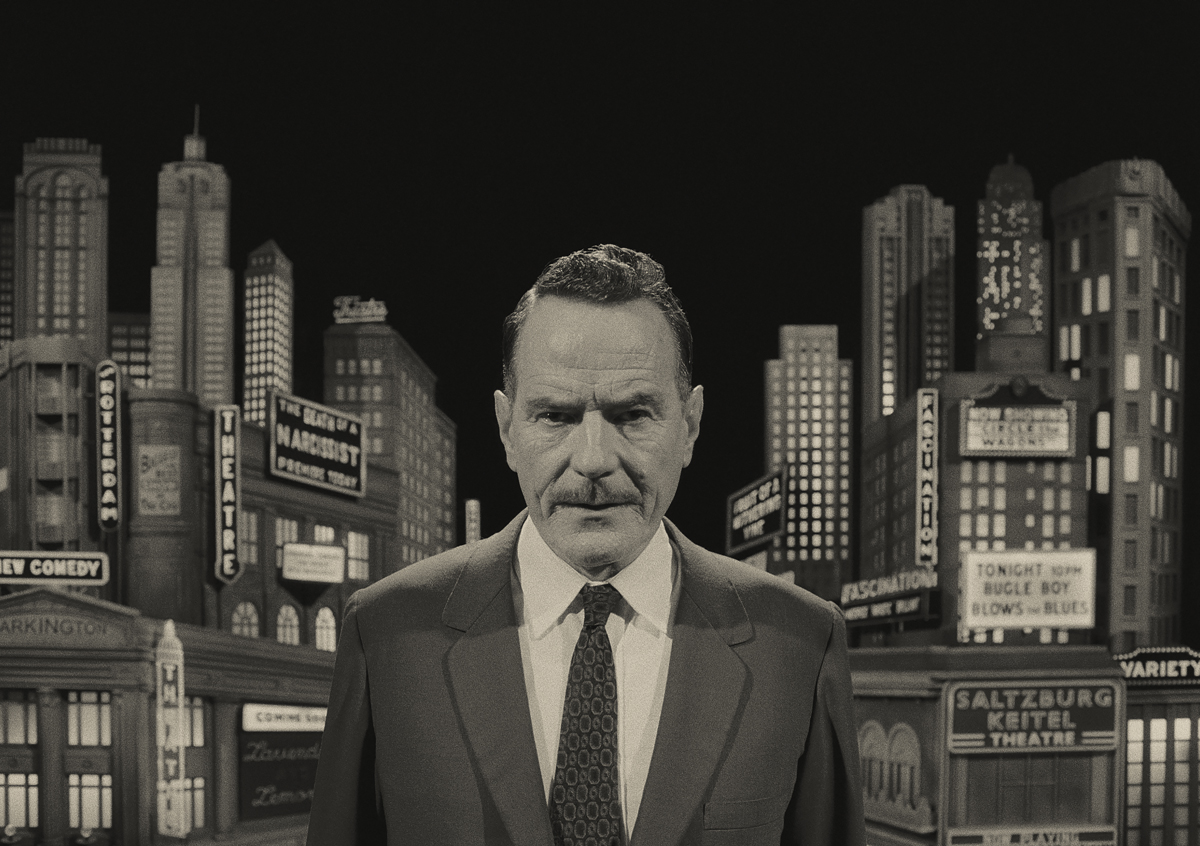

Bryan Cranston as the Host in Asteroid City. Courtesy Pop. 87 Productions / Focus Features.

In Asteroid City, Anderson’s teleplay-within-the-film comprises most of the movie, which starts in earnest after a prologue in which a television host (Bryan Cranston, channeling Rod Serling) introduces what we’re about to see as a broadcast of a long-running theater piece authored by Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), a Wyoming-born playwright specializing in dramas of the Great Plains. The setting of Asteroid City, which takes place in 1955, is the eponymous Southwestern backwater burg (pop. 87), a collection of rental bungalows, one immaculately spit-polished diner, and a research observatory built around a yawning meteor crater. As the teleplay begins, the sleepy town’s paltry tourist trade picks up with the arrival of a convocation of Junior Stargazers and Space Cadets—whiz-kid teen inventors with their eyes fixed on the possibilities of a bright, high-tech future—and their accompanying parents, nursing obscure hurts from disappointing pasts. Among the chaperones are Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), a recently widowed war photographer, and Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a Hollywood actress. She will pursue a furtive romance with Augie, while Augie’s son, Woodrow (Jake Ryan), pines after Midge’s daughter, Dinah (Grace Edwards), during a period of government-imposed quarantine following an alien sighting.

Jason Schwartzman as Augie Steenbeck and Scarlett Johansson as Midge Campbell in Asteroid City. Courtesy Pop. 87 Productions / Focus Features.

The film’s opening notwithstanding, the teleplay section of Asteroid City is not an attempt to pastiche the style of ’50s anthology drama series like Playhouse 90, Studio One, or Kraft Television Theatre; nothing in its subject matter, dialogue, or camerawork particularly suggests the sort of thing that one might have seen on a cathode-ray tube at any time during the Eisenhower administration. It is shot in anamorphic scope and in the vibrant tones of vintage five-color “linen” postcards, featuring a range of pastels standing off against a desert backdrop craggy with red-rock formations that court comparison to Chuck Jones’s Wile E. Coyote Looney Tunes, complete with a “meep meep”-ing roadrunner puppet. In fact, the teleplay Asteroid City, with its wunderkind youths, walking wounded grown-ups, and wombat-eyed alien visitor torn from an Edward Gorey sketchbook, evokes nothing so much as a Wes Anderson film.

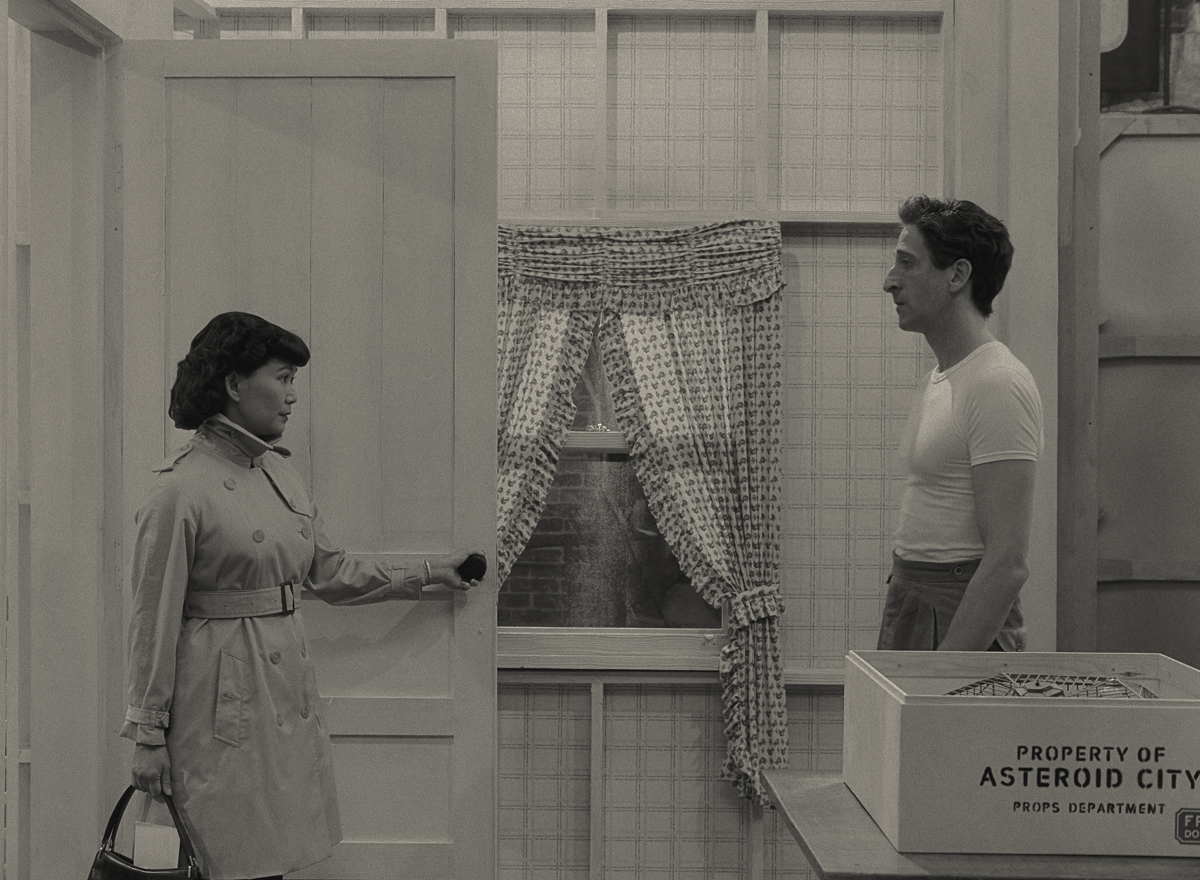

Hong Chau as Polly Green and Adrien Brody as Schubert Green in Asteroid City. Courtesy Pop. 87 Productions / Focus Features.

The backstage scenes in Asteroid City, involving Cranston’s host, Norton’s Earp, and a number of crew and cast members appearing out of character, are likewise Andersonian in staging, but shot in Academy ratio and black-and-white, and populated with personages suggesting inspirations from the world of mid-century American theater and movies. Earp, in the staked-out regionalism of his subjects, his steady diet of cocktails and pharmaceuticals, and his homosexuality, is something of a Tennessee Williams or William Inge. The play’s originating director, Adrien Brody’s Schubert Green, an oversexed, strapping satyr bulging out of his white T-shirt, is an amalgam of Marlon Brando and Elia Kazan, with a dash of Arthur Miller to boot. (His wife, played in a single scene by Hong Chau, has left him for a Major Leaguer.) The acting studio in which various performers featured in the Asteroid City teleplay are seen honing their craft can only be a surrogate for the Actors Studio, with a Lee Strasberg stand-in, Saltzburg Keitel, played by Willem Dafoe. Finally, the film’s evocations of Bus Stop and The Misfits connect Johansson’s self-consciously tragic bombshell, who appears much the same onstage and off, to Marilyn Monroe. (It’s more than once observed that, like Monroe, the woebegone Campbell is “actually a very gifted comedienne.”)

Scarlett Johansson as Midge Campbell in Asteroid City. Courtesy Pop. 87 Productions / Focus Features.

The behind-the-scenes talent in Asteroid City, much like the characters in the teleplay, fall into bed with one another, walk out on one another, or otherwise disappear from one another’s lives. Anderson’s addition of this backstage element links to his conjuring of key players in the popularization of the Method, a technique that asks actors to draw on their lived experiences in order to deliver performances of greater sincerity and veracity. Through Anderson’s pulling back the curtain on vignettes of love and loss in the lives of the “real” talent behind the “staged” production, we may receive a privileged glimpse of the raw emotional materials made use of in the fiction—though, as Cranston’s host establishes from the get-go, both are in fact inventions, and Asteroid City “is an imaginary drama created expressly for the purposes of this broadcast. The characters are fictional, the text hypothetical, the events an apocryphal fabrication.”

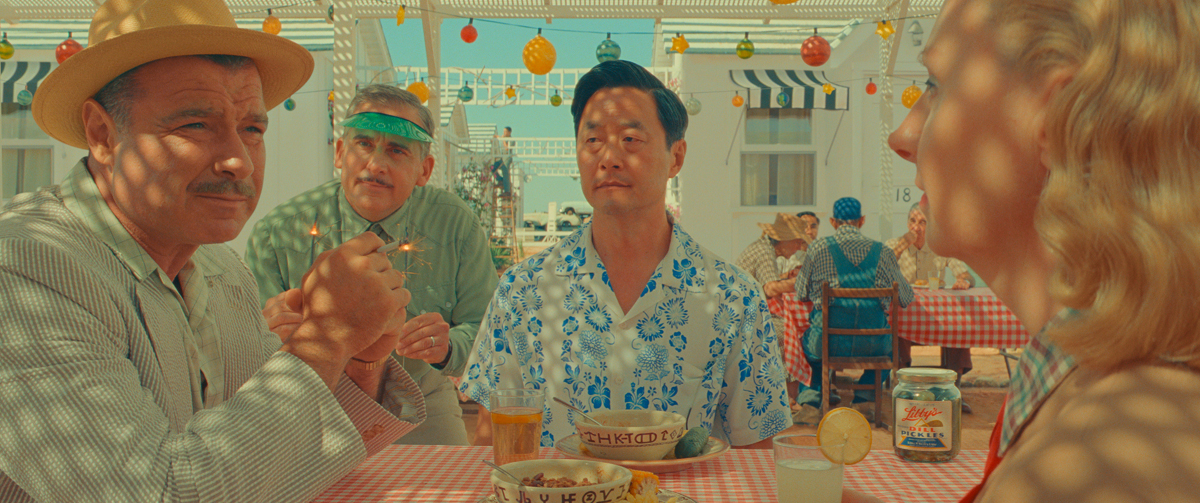

Liev Schreiber as J. J. Kellogg, Steve Carell as Motel Manager, Steve Park as Roger Cho, and Hope Davis as Sandy Borden in Asteroid City. Courtesy Pop. 87 Productions / Focus Features.

By nesting his fiction inside a fictionalized reality, Anderson, the grand fabricator who constructed his all-American small desert town on the Spanish plains, may be challenging the assumption of the Method and most any art-making practice premised on the idea of pure or authentic expression—or, alternately, intimating the presence of another real backstage beyond the artificial “backstage,” from which depths of feeling suffuse the closed world(s) of the film. Perhaps the fact that there’s an American movie scheduled for wide release that shows even a modicum of structural experimentation and intellectual ambition should be enough to make one grateful, but for a film doused in declarations of suffering and loss, Asteroid City delivers only a muffled emotional impact. Anderson’s long-standing tendency to fill his films with as many famous faces as possible, like undergraduates cramming into a phone booth, here results in an excrescence of thin subplots and one-note characterizations: a bearish Liev Schreiber, a winsomely flustered Maya Hawke, a gruff Tom Hanks in the Bill Murray middle-aged sad-sack role. It’s worth noting that Anderson’s best and most affecting movie of the past ten years, 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, was also his last to benefit from a single pivotal performance distinctive enough to carry the film, that of Ralph Fiennes’s dandified guttersnipe concierge.

Jake Ryan as Woodrow Steenbeck, Grace Edwards as Dinah, Ethan Josh Lee as Ricky Cho, Aristou Meehan as Clifford, and Sophia Lillis as Shelly in Asteroid City. Courtesy Pop. 87 Productions / Focus Features.

The Grand Budapest Hotel, too, makes use of an elaborate framing narrative, but the device is moving precisely because of the direct connection between storyteller—F. Murray Abraham, narrating the 1932-set events of the film that he witnessed as a young man, from the perspective of 1968—and the story told. In the case of Asteroid City, it’s baffling to imagine why a pack of lefty Group Theatre–veteran types would be expending time and sweat on a production celebrating plucky science-fair superkids given to saying things like “Yipe!” and “Howdly-dee” in the age of the A-bomb. (A mushroom-cloud cameo offers one clue that catastrophe may be the spoils of scientific progress, but this falls rather short of the apocalyptic vision of, say, Williams’s “A Knightly Quest.”) In the age of STEM-degree propagandization, Silicon Valley’s ardent pursuit of a post-human society, and six seasons of Young Sheldon on CBS, it’s also worth wondering why Anderson felt compelled to put forth a paean to these li’l prodigies—one that’s long on lugubrious mournfulness but short on comic piquancy. It’s a pity, because Anderson’s actually a very gifted comedian.

Nick Pinkerton is the author of the book Goodbye, Dragon Inn, available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series. His writing on cinematic esoterica can be found at nickpinkerton.substack.com, among other venues. The Sweet East, a film from his original screenplay directed by Sean Price Williams, premiered in the Quinzaine des Cinéastes section of the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.