Simon Reynolds

Simon Reynolds

Soundtrack to the bubble economy: a double album collects Japan’s 1980s “interior music.”

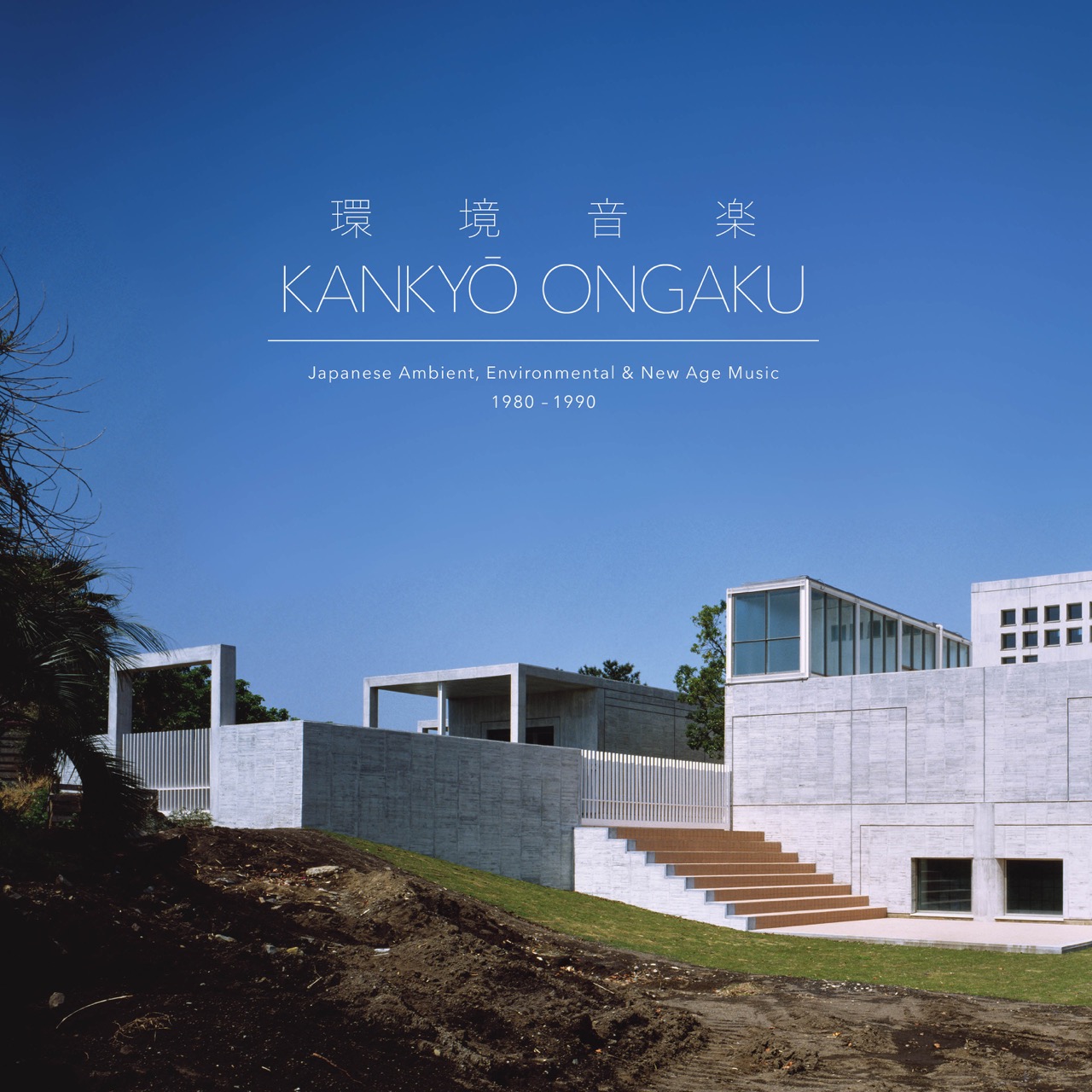

Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980–1990, Light in the Attic

• • •

“Curated” is an over-applied word in the contemporary music world. Typically, it’s used to lend a gloss of unwarranted elevation to practices that would be better described using humble existing terms: making a compilation, booking a festival lineup, spinning records. Now and then, though, “curated” is thoroughly deserved: rare occasions where the selection and sequencing really does reframe our understanding of an era or area of music, upturning settled ideas and revealing new vistas of pleasure.

One notable feat of creative curation in recent years was a pair of mixes released online at the start of the decade bearing the intriguing title Fairlights, Mallets and Bamboo. The work of Portland-based musician Spencer Doran, these unofficial compilations circulated widely and sparked an interest in an entire realm of 1980s Japanese ambient music whose existence most people outside East Asia had barely suspected. The “Fairlights” in the title refers to an iconic brand of sampler, which infused the music with a charmingly dated early-digital aura. “Mallets” nods to the marimba-like tuned-percussion chimes that sometimes figure in this music’s sound-palette, while “Bamboo” evokes the extended family of Japanese flutes that includes the hocchiku and the shakuhachi. While this music does have European and North American counterparts—early ambient releases by Brian Eno and Harold Budd, the ECM label’s post-fusion “chamber jazz,” New Age’s aural soma—there’s a calligraphic delicacy to the subtle synth-daubs and subdued rhythm-pulses that feels distinctively Japanese.

Fascination for this era has continued to grow, with key records like Midori Takada’s Through the Looking Glass and Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Music for Nine Post Cards reissued in the last couple of years. Now, nearly a decade after the first Fairlights, Mallets and Bamboo mix, Doran has compiled a double-album survey for Seattle’s Light in the Attic label, Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980–1990. Kankyō ongaku translates as “environmental music,” but that is just one of several terms that the Japanese musicians used to describe what they were doing. Another is “interior music,” which at least in its English rendering feels like wordplay connecting the idea of audio décor for the domestic living space with a notion of spiritually inward contemplation. And then there’s BGM, an acronym for “background music,” which further served as the title of a 1981 album by Yellow Magic Orchestra.

Interior of the Iwasaki Art Museum buildings designed by Fumihiko Maki, shown on the inner sleeve of the second Kankyō Ongaku LP. Photo: Osamu Murai. Image courtesy Kumi Murai and Teruko Murai.

Another neologism that resonated with these Japanese musicians came from overseas: “fourth world music,” a concept coined by the trumpeter Jon Hassell to describe mutually enriching encounters between modernity and traditional ethnic music, in which electronic techniques coexist with acoustic instrumental textures. Two of the most crucial musical figures in ’80s Japan—Haruomi Hosono and Ryuichi Sakamoto, both formerly of Yellow Magic Orchestra—were already thinking along similar lines. Hosono talked about “sightseeing music,” a style of cosmopolitan pastiche and sonic tourism, while Sakamoto titled one of his solo records Neo Geo to celebrate a similar pan-global approach.

Japanese popular music has always had a flair for assimilating ideas from outside the islands, sometimes making disconcertingly close facsimiles of Anglo-American and European styles and at other times generating startling mutations and recombinant forms. As Doran explains in his Kankyō Ongaku liner notes, a 1970s vogue for Satie’s music in Japan influenced the following decade’s “interior music” boom. And certainly you can hear the link between the idyllic yet wistful slow-motion melodies of Interior’s “Park” and Yoshio Suzuki’s “Meet Me in the Sheep Meadow” and the poignant cadences of Satie’s solo piano works like “Trois Gymnopédies.” Satie’s proto-ambient notion of “furniture music” was also inspirational. But if this imported idea took hold, it’s because it struck a shimmering chord with Japan’s existing cultural traditions, ideals of balance and grace manifested in things like the suikinkutsu, a garden ornament that turns the dripping of water into a soul-soothing sonic backdrop.

Satoshi Ashikawa (right) with Harold Budd. Photo: Sound Process.

Most of the pieces on Kankyō Ongaku are designed to work as an environmental tint, closer to good lighting or incense than music as commonly understood: a nonintrusive complement that surrounds and enhances everyday activity. Satoshi Ashikawa, whose “Still Space” opens the first disc, aimed to create a sound that would “drift like smoke.” Given that most of this music doesn’t actively seek to command your full attention, pointing to standout tracks might be missing the point altogether. Still, Toshi Tsuchitori’s “Ishiura” can withstand a concentrated listen: generated using the bell-tones of a volcanic stone unique to his hometown Sanuki, it resembles the crystalline ripple of a wind chime slowed down and magnified. Inoyama Land’s “Apple Star” reminds me of the old science fiction dream of an elevator that takes passengers from the earth’s surface to the threshold of outer space: listening, I picture a glass-sided vessel ascending through a column of stars. Hiroshi Yoshimura’s “Blink” scatters electric piano notes so glistening you can almost see your reflection in them. Closing out the second disc, Hosono’s “Original BGM” is a sixteen-minute-long cycle of descending melody painted in synth hues of just-bearable brightness, as if you are squinting directly into a setting sun.

Haruomi Hosono. Image courtesy the Masahi Kuwamoto Archives.

“Original BGM” was commissioned by the department store chain Muji, which was looking for sounds to match well with Ikko Tanaka’s interior design. One of the most intriguing things about the Japanese ambient school of the 1980s is how closely this experimental left-field sound was enmeshed with corporate culture during the “bubble economy” years. Pieces were composed for retail outlets and fashion runway shows, or as soundtracks to advertisements for domestic appliances and luxury goods. Takashi Kokubo’s “A Dream Sails Out to Sea—Scene 3” was originally recorded for and distributed with a Sanyo air-conditioning unit, bolstering the product’s selling point—its alleged ability to deliver a tropical atmosphere to any household. On the face of it, the commercial function of much of this music feels dissonant given the spiritual associations that ambient and New Age music generally carry. But in another way, it speaks to the resilience of traditional values amid the hectic hyper-capitalism of late-twentieth-century Japan.

Takashi Kokubo. Image courtesy Studio ION.

The rediscovery of Japanese ambient is part of a larger drift over the last few years toward tranquil sounds like New Age, drone, and field recordings on the part of esoteric music fiends. There’s a discernibly increased appetite out there for sonic attributes that start with the letter “s”: slow, soft, still, spacey/spatial, serene. Japanese has its own word that covers several of these shades of meaning and that is revealingly sibilant: shizukesa. Perhaps this reflects the universally lulling and hypnotic power of shhhh.

Hipsterism and simple curiosity are clearly aspects of these processes of discovery and rehabilitation. Internationally foraging pop group Vampire Weekend, for instance, have sampled one of Hosono’s compositions for Muji on their new song “2021,” a taster for the forthcoming album Father of the Bride. But it’s likely that other factors are at work too behind the attraction to Japanese interior music and similar emollient styles. Inchoate spiritual longings, perhaps, to escape the pummeling pace of digital life, an audio analogue to the self-care and wellness movement. The hope that the churning hollowness of online existence can be healed—or at least temporarily relieved—by a different kind of emptiness: the cleansing calm of music that hovers at the very edge of nonexistence.

Simon Reynolds is the author of eight books about pop culture, including Retromania, the postpunk chronicle Rip It Up and Start Again, the techno history Energy Flash, and Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the 21st Century. Born in London, currently resident in Los Angeles, he is a contributor to publications including The Guardian, Pitchfork, and The Wire, and operates a number of blogs centered around the hub Blissblog.