Yasmine Seale

Yasmine Seale

An exhibition of work by modern Arab artists whose unclothed subjects reveal an expansive range of traditions and subversions.

Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, installation view. Courtesy Wallach Art Gallery. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, curated by Kirsten Scheid, Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, Lenfest Center for the Arts, 615 West One Twenty-Ninth Street, New York City, through January 14, 2024

• • •

There is a huddle of women in the gallery, crowded around the same painting. Six heads can be made out, and a forest of legs, but these figures are otherwise hard to distinguish. Each of them is wrapped—swaddled—from head to toe in black. They blur into a somber cloud in the pink room. Follow their scowls: high on the wall, two naked bodies face each other, filling the frame. One is reclining; the other stands, arms raised, in lazy contrapposto. Their knees are touching. Their unembarrassed languor must have drawn the crowd. One viewer’s arm has flown up to her face as if to shield her eyes. In disapproval? Shock? Same old story, you think. Women against women, zealots against the unzipped. Another day at the shame factory.

Omar Onsi, À l'Exposition (Young Women Visiting an Exhibition), 1932. Oil on canvas, 17 3/4 × 14 3/4 inches. Courtesy Mir Samir Abillama.

Look again. These austere creatures, are they really here to scold? Details begin to surface on their high-heeled shoes (a red sole here, a buckle there) and a range of grays about the calves, suggesting variance in the sheerness of the stockings. Waists appear. Fabric falls crisply at the knee. What looked like self-denying shrouds are in fact trim, voguish ensembles: cape-like pelerines over taffeta skirts. The woman is not screening her eyes but adjusting her yashmak, a diaphanous veil worn by the upper classes, which enhanced what it pretended to conceal. She is not shocked by what she sees, only aware that she is seen. Not scowling but posing.

Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, installation view. Courtesy Wallach Art Gallery. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

Omar Onsi’s painting À l’Exposition (1932) is the first work displayed in Partisans of the Nude: an Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920–1960, on view at the Wallach Art Gallery. Curated by Kirsten Scheid, it sets out to correct two misconceptions: that modern Arab artists did not paint nudes, and that Arab audiences did not tolerate them. The double take is its method, and it is typical of the subtle approach adopted throughout that an exhibition about baring it all should open with an image that reveals itself by degrees, teasingly. Only on my second visit did I notice a small bright swoosh in the mass of dark cloth: a hand resting, dramatically arched, on a cocked hip—an echo of the naked model’s jaunty pose. Only then did the museumgoers’ severity resolve into something more complex. This activity—looking and being seen looking at nudes—is an accessory to their way of life, not an affront to it. A sign of distinction, like the stretch of gauze around their heads.

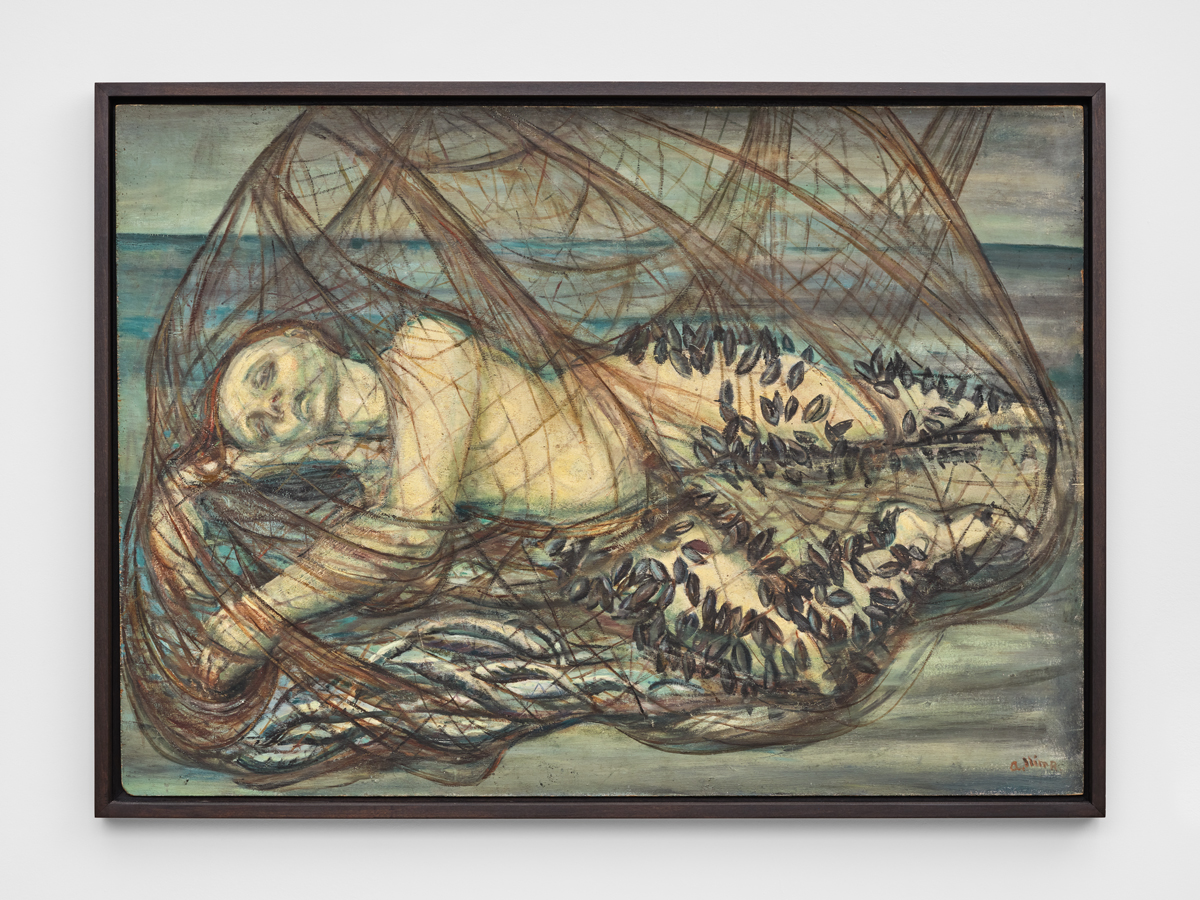

Amy Nimr, Untitled (Girl with Fishnet), ca. 1928. Oil on canvas, 29 1/2 × 41 5/16 inches.

This is an excavation—a partial survey of a buried history. If nudes did get painted (and drawn, and sculpted), they were rarely institutionalized. Many of the works here come from private collections or the artists’ heirs. A smaller version of the show, focused on Lebanon, opened in Beirut in 2016. This edition, spanning artists from Algeria to Bahrain, incorporates new research into local histories to gesture at wider forms of social change in the long aftermath of empire. It presents what the wall text calls “not-yet Arabs,” people who were born Ottoman subjects and died citizens of fledgling states. Their use of the human figure describes a zigzag path of liberation and self-fashioning. One room consists only of nudes in coastal landscapes. In a towering canvas by Amy Nimr (ca. 1928), a fishing net lifts a gaunt woman, dead or sleeping, out of the waves. But has it come to cage her or to rescue her? She is already half reef, burdened with mussels. The shore is a watery space of becoming; bodies at the brink throw off more than their clothes.

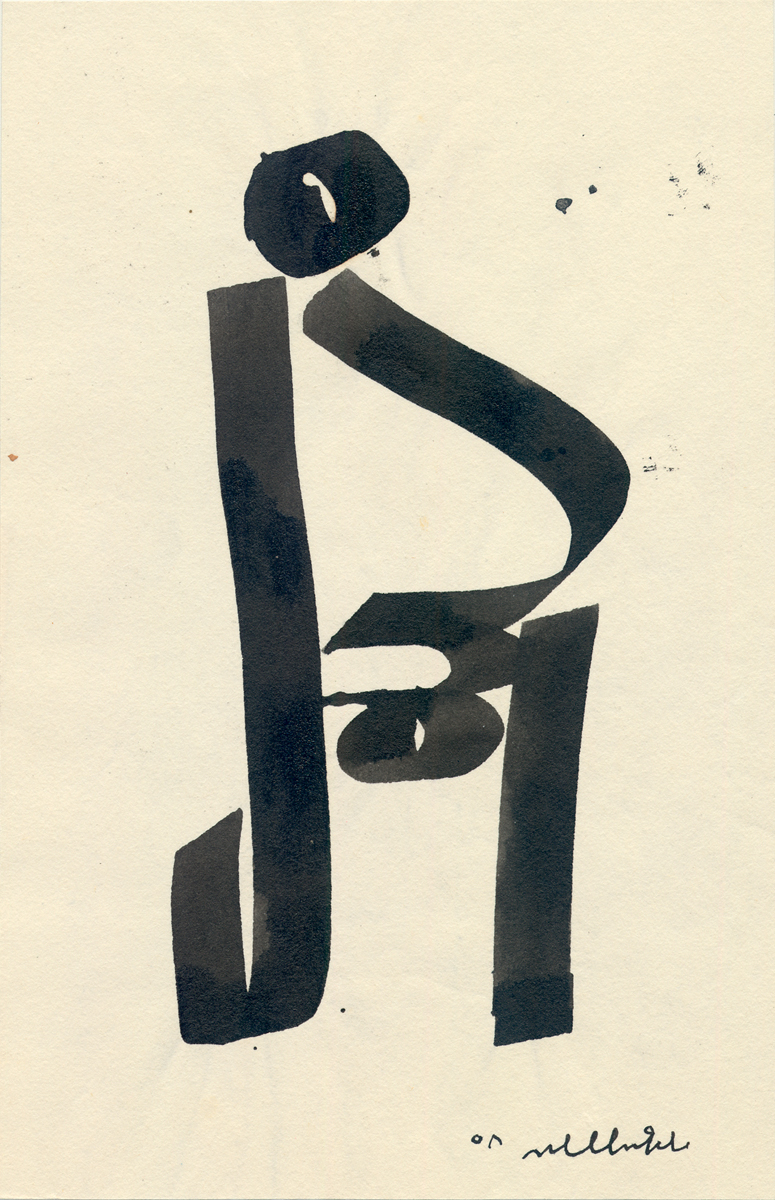

Hamed Abdalla, Al-Haml (Pregnancy), 1958. Ink on paper, 8 1/4 × 5 15/16 inches. Courtesy Dar Abdalla.

Nimr studied in London and would later host the Egyptian Surrealist group Art and Liberty in her Cairo salon. Most of the other artists featured here also trained in colonial metropoles, cutting their teeth on academic studies in charcoal and sanguine before returning home. But the nude wasn’t only a Western import, nor even a modern one. Hamed Abdalla, the son of poor farmers from Upper Egypt, received little artistic training except in traditional calligraphy. While copying a line inscribed on a twelfth-century pot, he saw bodies emerge from the curved glyphs. From the 1950s on, Arabic letters became his means of figuration; there is a beautiful series of works on paper where the word for pregnancy, Al-Haml, takes on a bellied form. If the nude was, as Scheid puts it, a “technology of modernization,” so was the alphabet. Another pioneer of lettrism was Jamil Hamoudi, who defended his dissertation at the Sorbonne on abstraction in ancient Iraqi art and would go on to forge, back in Baghdad, a modernist vernacular from the myths of Mesopotamia. His diaries from the 1940s, full of sketches, are laid out chronologically; the earliest nudes he drew, inspired by Babylonian goddesses, are also the least representational. There are other antiquities; there is a history of art where cubism comes before classicism.

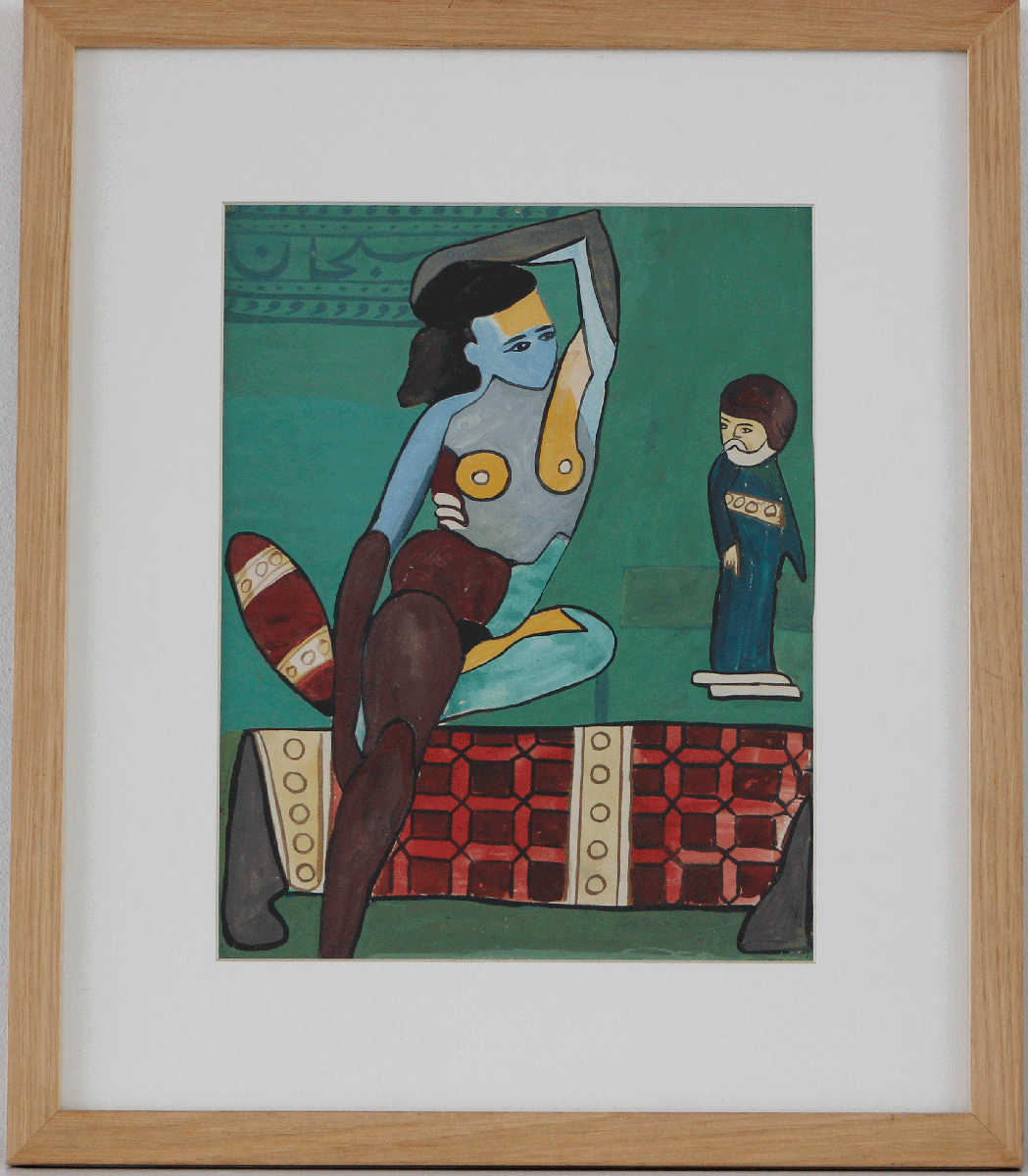

Saloua Raouda Choucair, Subhan (May He Be Glorified), 1949. Gouache on paper, 12 3/8 × 9 5/8 inches. Courtesy Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation.

The catalog lists, among the show’s questions, “Who is Arab? . . . How does Islam organize life? . . . How are divine and human interrelated?” But the most interesting pieces slip the nets of discourse, puncture grandiosity. It is the works by women, the nude’s conventional subjects, that land the sharpest blows in their tangle with tradition. A small gouache by Saloua Raouda Choucair, ironically titled Subhan (May He Be Glorified) (1949), pokes fun at various masters: in a domestic interior, a woman dressed only in colored pigment is locked in a staring match with a tiny, bearded scholar who points sternly at his toes, willing her into submission. She sits with an elbow raised, pressed against the frame’s upper edge. Many nude paintings depict this pose; only here did I register it as a stress position. Dreamlike ink drawings by the Palestinian artist Juliana Seraphim, shapeshifting hydras of flowers and birds, offer erotic visions of emancipatory flight. And there are moments of pure delight. A gloriously playful oil by Huguette Caland reimagines thigh gap as some wavy Nile, chafing skin its earthy shores, the rectum its delta.

Shaker Abdulnabi-Shalem, The Odalisque (after Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres), 1947–48. Colored crayons on paper laid on cardboard, 19 11/16 × 35 7/16 inches.

One of the most intriguing works is a copy of Ingres’s Grande Odalisque in colored crayon by a teenage Shaker Abdulnabi-Shalem (1947–48), which hung in the home of his Jewish family in Mosul like the portrait of an ancestor. The paper is now faded, stained; time has kinked the neoclassical image into abstraction. And there are surprises among the ephemera. From 1930s clippings we learn about Ansar al-Uri, a nudist group active on the beaches of the Eastern Mediterranean, and about Makshouf (Exposed), a magazine against political corruption that included pornographic prints and stories. And, from 1968, a snapshot of the Tunisian artist Fêla Kefi Leroux in her studio, kaftan-clad, midway through a sketch of a French girlfriend au naturel. If there exists another photograph from the twentieth century of an Arab or African woman painting a white model, I’d like to see it.

Ahmed Morsi, Adam and Eve, 1959. Oil on panel, 46 1/32 × 35 inches. Courtesy Ghada Barsoum. © Ahmed Morsi.

The Wallach, despite being six floors up a Renzo Piano–designed aluminum monolith on Columbia University’s satellite campus in West Harlem, is free and open to everyone. But if there were a price of entry, one work here would be worth it. After seeing Ahmed Morsi’s Adam and Eve (1959), is it possible to imagine the first nudists as anything other than taut and bug-eyed, lost in grape-colored haze, too haunted or aroused to notice the smooth jade beast—part sphinx, part baby seal, both cuter and more terrifying than a snake—thrusting a Red Delicious into the purple void?

Yasmine Seale is a fellow of the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. Her translations from Arabic include The Annotated Arabian Nights, published by W. W. Norton.