Margaret Sundell

Margaret Sundell

A new show highlights the celebrated art director’s innovations in photography and design during his mid-century reign at Harper’s Bazaar.

Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me, installation view. Photo: Alexander Rotondo. © Barnes Foundation.

Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me, curated by Katy Wan, Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia,

through May 19, 2024

• • •

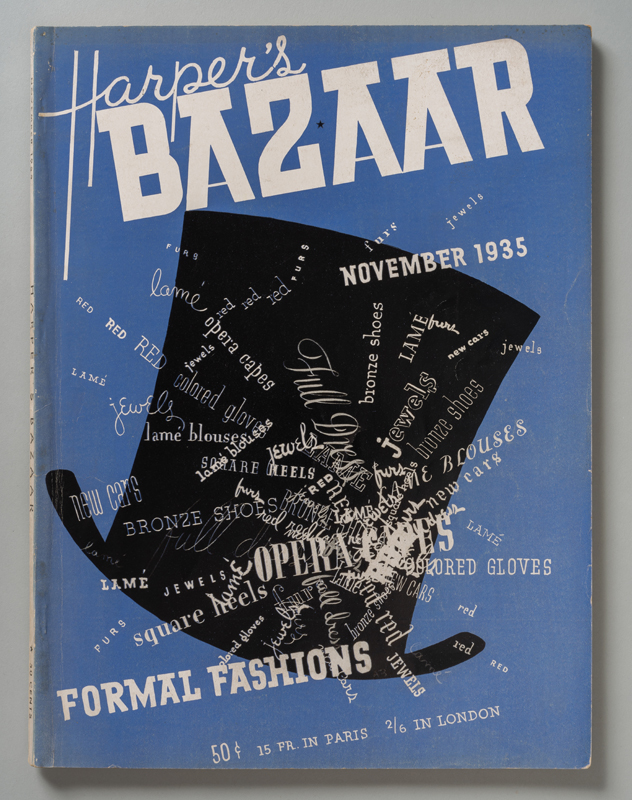

I first encountered Alexey Brodovitch—the legendary art director of Harper’s Bazaar, where he reigned from 1934 to 1958—in the New York Public Library. Back issues of the magazine hadn’t been transferred to microfiche when I met him, during research for my dissertation on Man Ray. As I sat in the library leafing through magazines he designed, I could almost feel with my fingers the excitement of his layouts, the way he exploded corseted columns, liberating image and text, which often appeared at dynamic angles; the way he bled single pictures across double-page spreads, endowing them with an immersive appeal. Consider the cover he created for the November 1935 issue: defying gravity, its elements float against a midnight-blue expanse, the name Harper’s set off-kilter, a cut-out black top hat similarly askew. Atop the hat twirls a pinwheel of magical phrases: “bronze shoes,” “lamé blouses,” “opera capes.” In transforming Harper’s, Brodovitch applied the principles of modernist design to the realm of the woman’s magazine. He also added a dash of surrealism. For the September 1934 issue, the designer invited Man Ray to contribute a rayographic “impression” of “a new fashion ‘coming over’ the shortwaves”: a shadowy figure of an elongated, peplumed gown set on netting, whose undulations are echoed in a wavy, column-free caption (such mirroring of pictures and words can be seen throughout Brodovitch’s career).

Harper’s Bazaar, November 1935. Collection of Vince Aletti. Courtesy Harper’s Bazaar, Hearst Magazine Media, Inc.

Brodovitch’s backstory: he hailed from a White Russian family, fled to Paris in 1920, and enmeshed himself in the city’s avant-garde milieu. Starting with odd jobs, notably painting backdrops for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, he went on to become a successful designer (accounts included restaurants and department stores). Ten years later, Brodovitch decamped for America, initially Philadelphia, where he taught at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, and later New York, where he took up his post at Harper’s. Its then newly appointed editor, Carmel Snow, tasked him with revolutionizing the magazine—in his words, by creating “ ‘shock value’ on every page.” Harper’s Bazaar is the subject of one of five galleries that comprise Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me, currently on view at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. This compact show takes its title from the famous injunction the terse, exacting designer issued his photographers—both those who worked for him at the magazine and those who studied in his Design Laboratory, an experimental workshop he taught for many decades. “Astonish me,” he told them, and they did, creating images that scrambled convention, defied expectation, and bristled with novelty. Appropriately titled, the Barnes exhibition emphasizes Brodovitch’s relationship with the photographers who answered his appeal and otherwise entered his orbit, like Richard Avedon, Lisette Model, Lillian Bassman, and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me, installation view. Photo: Alexander Rotondo. © Barnes Foundation. Pictured, center back wall: Richard Avedon, Dovima with elephants, evening dress by Dior, Cirque D’Hiver, Paris, 1955.

All are featured in the room devoted to Harper’s, most prominently Avedon, Brodovitch’s protégé and greatest collaborator. His cover shots are housed in a vitrine, while an outsize print of his Dovima with elephants, evening dress by Dior, Cirque D’Hiver, Paris (1955) appears on a large, central wall. Avedon’s rendition of a beauty and her beasts is a perfect response to Brodovitch’s galvanizing enjoinder. Eschewing the studio or other typical locations for fashion shoots, Avedon took his model, dressed in a soigné Dior gown, to the circus and placed her between two pachyderms. The unexpected juxtaposition, with its play of tone and textures—shiny, satin fabric versus matte, wrinkled flesh—creates a scintillating frisson. Brodovitch not only inspired photographers but also had their trust, as is further revealed in this gallery’s presentation of Cartier-Bresson. The champion of the “decisive moment” allowed the Harper’s art director, and no one else, to alter his work. We see this in the contrast on view between Cartier-Bresson’s 1934 photo of two Mexican sex workers wearing heavy makeup and leaning out windows and the 1952 version from Harper’s. In the latter, highly dramatic, tightly cropped image, only one woman appears—and seems to be falling directly, almost violently, out of the magazine and into our space.

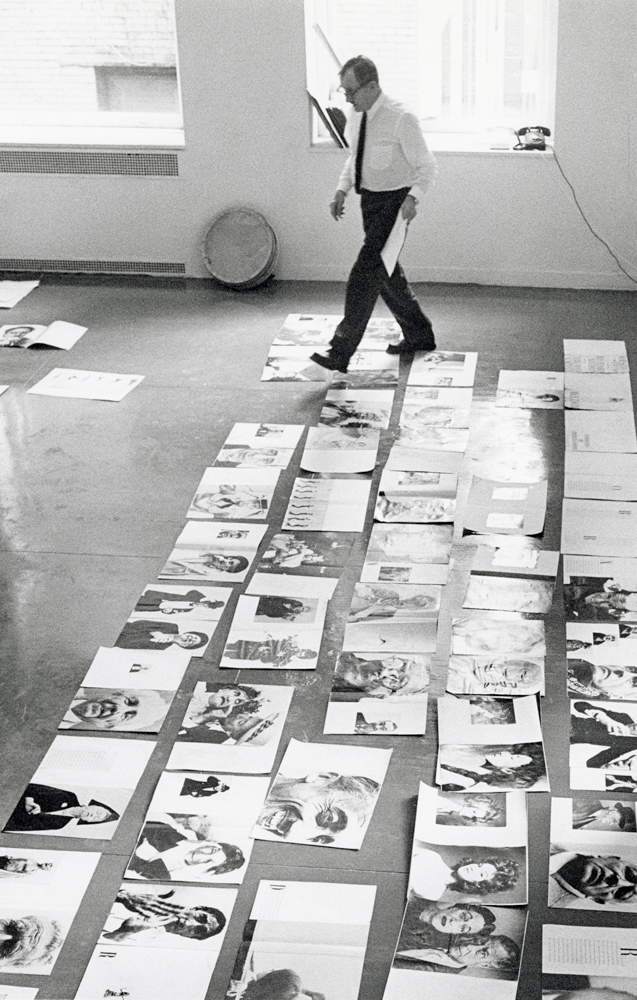

Alexey Brodovitch reviewing page layouts for Richard Avedon’s Observations, 1959. Photo: Hiro. © Estate of Y. Hiro Wakabayashi.

Brodovitch’s acute visual intelligence can also be seen in the display case devoted to the third and final issue of Portfolio—a short-lived publication founded by art director Frank Zachary and printer George Rosenthal, which ran from 1950 to 1951—one of a number of outside projects that enabled Brodovitch to expand his vision beyond the limited pages he was allocated by Harper’s. His raw material here is a set of pictures shot by Design-Lab student Hans Namuth that catch Jackson Pollock, crouching over a canvas, wet brush in hand, in the act of creating a drip painting. Brodovitch presents the photos in the form of contact sheets cut to resemble black-bordered film strips. The sequencing of images guides the eye, generating both a sense of movement and temporal unfolding that almost mimics Pollock’s process. The result is a powerful synthesis of subject, form, and viewer reception. There are few other places in the exhibition that reveal Brodovitch’s brilliance with interior spreads, and for those who know and love his layouts, this inevitably registers as a loss. But the move to focus on Brodovitch’s relationship with photographers still makes a lot of sense. A lesser-known facet of his career, it’s one with significant art historical consequences. The curatorial narrative also resolves certain pesky problems of exhibition design. Instead of peering into endless vitrines or perusing costly-to-produce facsimiles, visitors can mostly gaze with ease at images on a wall—images that, under Brodovitch’s aegis, defied assumptions of what a photograph could be.

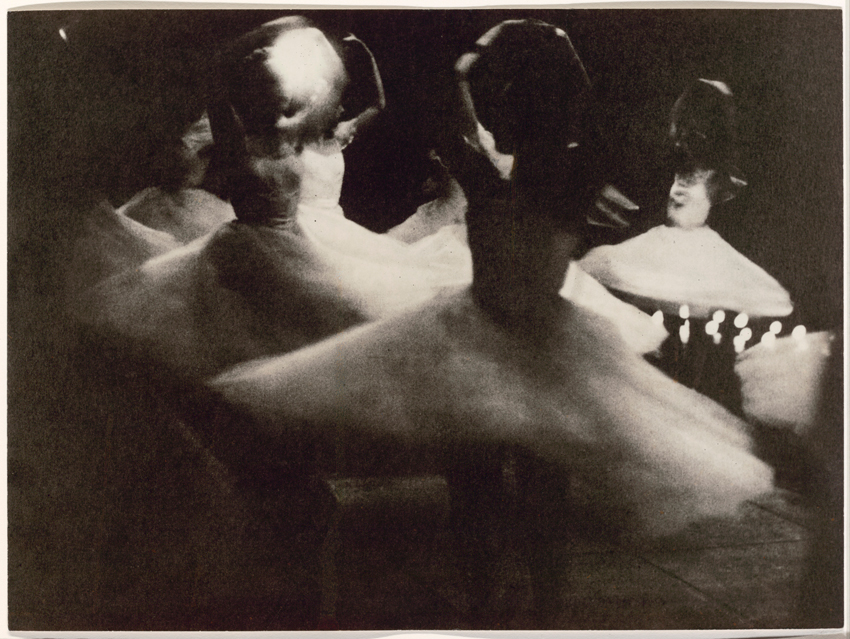

Alexey Brodovitch, The Sylphs (Les Sylphides), 1935–37. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago. Photo: Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource.

Fittingly, given its orientation, the show closes with the art director’s lone photographic venture, an illustrated book from 1945 titled Ballet, based on visits he made to various ballet companies between 1935 and 1937. Armed with backstage access, a 35mm camera, and slow, less sensitive film, Brodovitch willfully exploited his equipment’s limitations so that, in his pictures, movement blurs, stage lights flare. His shots are fragmentary, oblique. A radical departure from the razor-sharp photos then in vogue, Brodovitch’s deeply expressive images might be likened to the scrim of memory, as critic Christopher Phillips did in his 1981 essay in American Photographer—a recollection of the designer’s cherished youthful encounter with Diaghilev and his corps. With a print run of only five hundred, many lost in two house fires that decimated Brodovitch’s archives, Ballet is exceedingly rare. While its pictures grace a darkened gallery and appear in a slide projection mounted high on one wall, the book itself remains tantalizingly under glass. An impossible dream, in this context, but what I would give for the intimate, revelatory engagement with Brodovitch’s Ballet that I once had in the public library with Harper’s Bazaar.

Margaret Sundell is the editor-in-chief of 4Columns.