Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

In the Drawing Center’s comprehensive exhibit, an opportunity to see afresh the writer and artist’s dreams and contradictions.

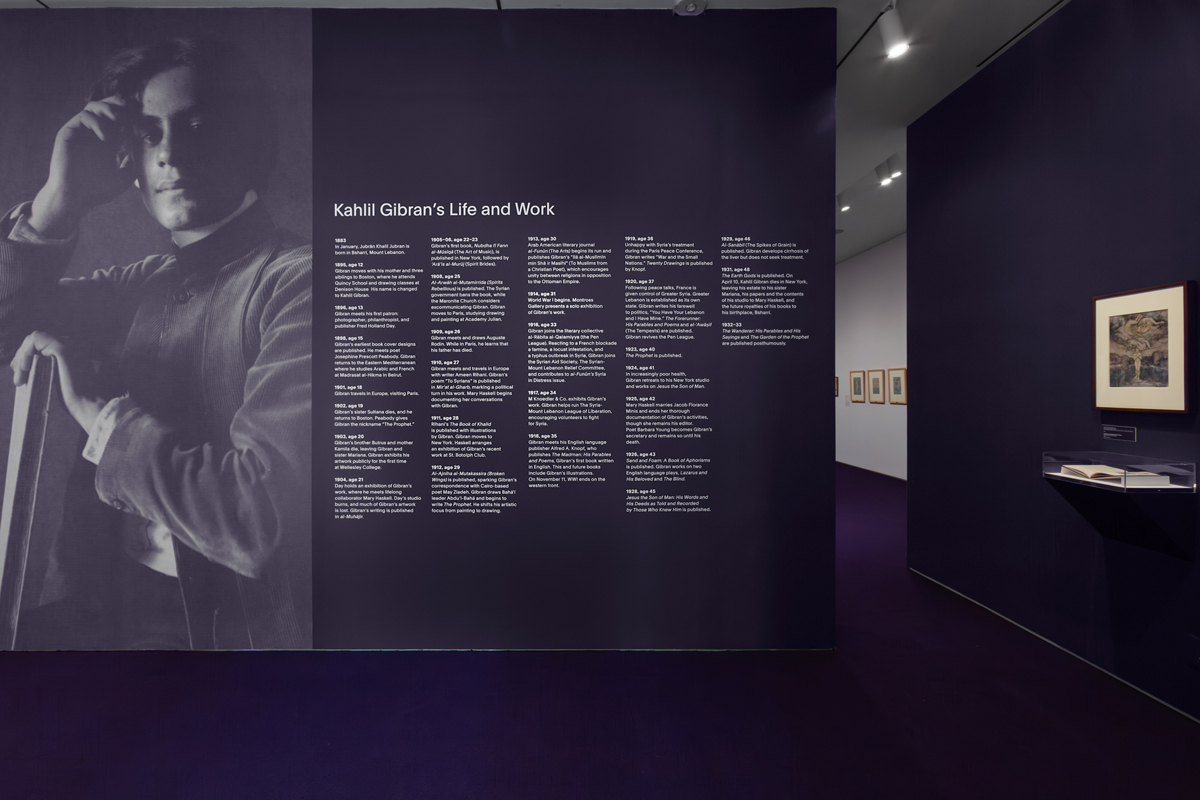

A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran, organized by Claire Gilman with Isabella Kapur and Anneka Lenssen, the Drawing Center,

35 Wooster Street, New York City, through September 3, 2023

• • •

For an ignorant reader like me, until now only passingly and somewhat cynically acquainted with the phenomenon of Kahlil Gibran, the exhibition of the fabled author’s lesser-known visual art at the Drawing Center is a jolting adjustment. Not necessarily because the charcoal and pencil drawings, watercolors, and offset lithographs on view are extraordinary—though maybe they are (whether or not Gibran was a talented artist is as much a source of anxiety for his scholars as the quality of his writing). But more for how the show, curated by Claire Gilman with Isabella Kapur and Anneka Lenssen, clarifies the blur of his legend, delicately pulling out even the unflattering complexities of his life, self-presentation, and reception, while simultaneously giving the viewer compass to take in his works on their own terms, loosened from the static cling of biography.

To allow for such a paradoxical experience (a choice that’s surely homage to Gibran’s own obsession with antinomy), the organizers devised two paths through A Greater Beauty: one an aesthetic approach, the other archival. The parallel itineraries amplify each other in a calibrated balancing act; the result is grounding, resuscitative, and remarkably reframes the work.

A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

One path goes around the main gallery’s lilac-hued perimeter, where fifty-six drawings and watercolors—many conceived as illustrations for his books, for which they would be photographed and transferred to black-and-white (usually) lithography—chronologically progress through Gibran’s shifting aesthetic concerns, all spaciously presented with little curatorial comment. The other path starts in the exhibition’s darkened antechamber, where a mauveine wall displays a biographical and historical chronology. This introduces one of the curators’ main goals: to square the man—who always lied about the facts of his life, who dreamed of transcending them—with his context.

A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

This effort continues in the center of the room, anchored by a freestanding wall painted violet and bearing four groups of drawings, all fairly academic portraits, which map Gibran’s networks of patrons, friends, spiritual and cultural idols, women on whom he erotically fixated. Six vitrines are also positioned here, bursting with letters, notes, marginalia, idle sketches, and lengthy object labels. Along with the robust exhibition catalog, these materials put forward a narrative of Gibran as wracked with contradictions, desperate to find out how to be in the world—a world that, no matter where he was in it, never quite seemed to want him there.

A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

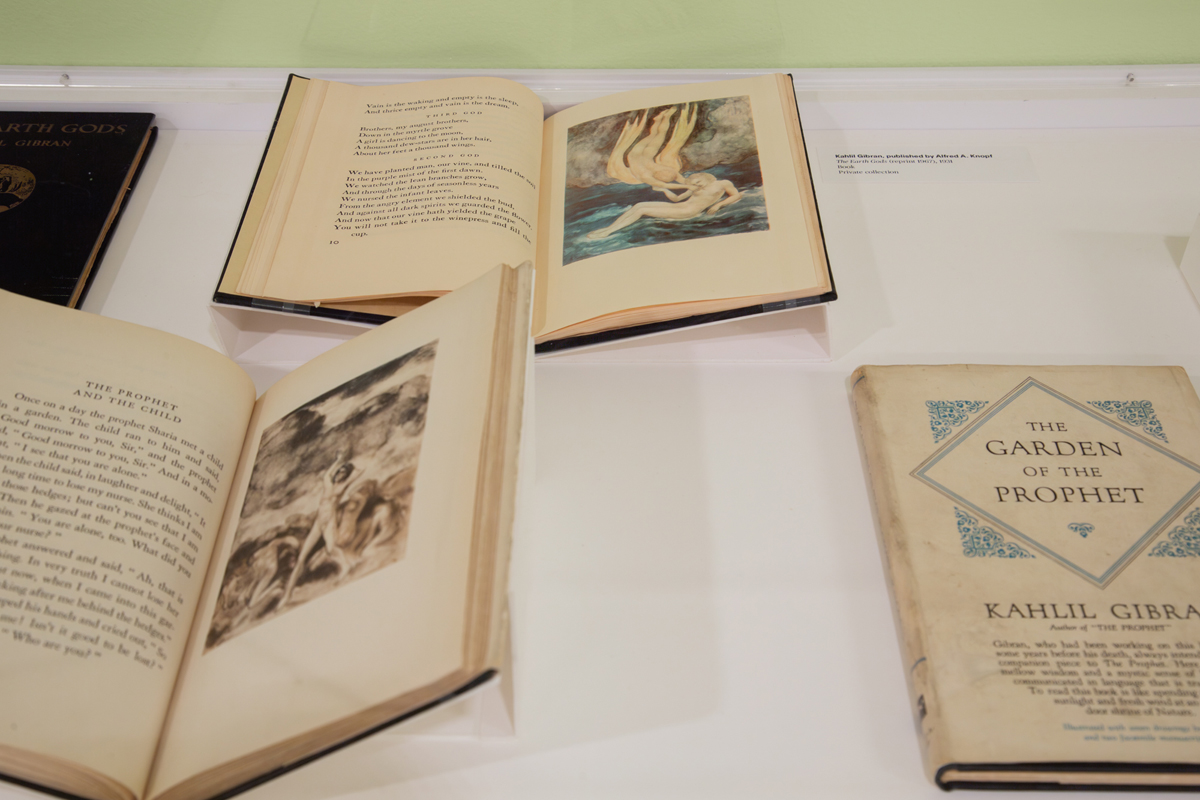

He was born in 1883 as Jubrān Khalīl Jubrān in a Mount Lebanon village in Ottoman Syria. When he was twelve, his mother packed him and his siblings up and headed for Boston to escape his deadbeat dad. Like so many others, he got a new name, the one we know him by now, when he arrived in America, thanks to a clerical misinterpretation at immigration. Gibran loved to paint and draw and eventually caught the eye of photographer and publisher Fred Holland Day, who enjoyed inviting “ethnic” children into his studio, dressing them up in fantasies of Orientalist garb, and taking their portraits (one of Gibran is reproduced on the title wall). The teen started designing book covers for him, some of which are on view in a vitrine at the exhibition’s start, along with his adolescent landscape paintings. Gibran’s mother worried about the nature of her son’s increasingly close relationship with Day, and, in 1898, sent the fifteen-year-old back to the Levant to study at a Maronite Christian school, where he learned how to write in Arabic—the language of his first books.

A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

Gibran spent much of his short life in motion. The woman he met after returning to Boston, who would unrequitedly love him and become his benefactor, champion, and emotional burden, Mary Haskill, whose archive furnished many of the facsimiles in the vitrines, funded his art studies in Paris. Also on Haskill’s dime, in 1911 Gibran moved to New York City, establishing his home on West Tenth Street in Greenwich Village. He wrote 1923’s indelible The Prophet in this studio, which he called his “Hermitage” and crammed full of things, including a meteorite Haskill had sent him, dug out of a crater in Arizona. He frequented the Little Syria neighborhood in lower Manhattan where several friends lived, here forming an Arab American literary society. These places felt at last like home, hard-won and self-made, though built on precarious foundations (Little Syria was razed not many years after Gibran’s death, the building that housed his studio a decade later).

A Greater Beauty: The Drawings of Kahlil Gibran, installation view. Courtesy the Drawing Center. Photo: Daniel Terna.

In New York, when he wasn’t writing or drawing, Gibran was agitating for US aid and intervention back in his homeland, riven with famine and wartime atrocities, its borders torn asunder. His supposedly progressive American friends disapproved of what they judged to be warmongering; they preferred Gibran in the role he had otherwise wholly adopted of unworldly Eastern sage. Critics would see Gibran’s construction of this personality as a mercenary self-Orientalizing for the American gaze, born of a cutting desperation for glory after a childhood in poverty, and accuse him, despite his activism, of abnegating his political responsibility to his native region. They would accuse him, too, of being terrible at writing in Arabic, writing they found as awkward and stilted as some would find his art to be derivative and anti-modern. (Gibran responded to the former charge in a 1924 prose poem, “You Have Your Language and I Have Mine”: “You have preserved its rigid cadaver / and I shall have its soul.”)

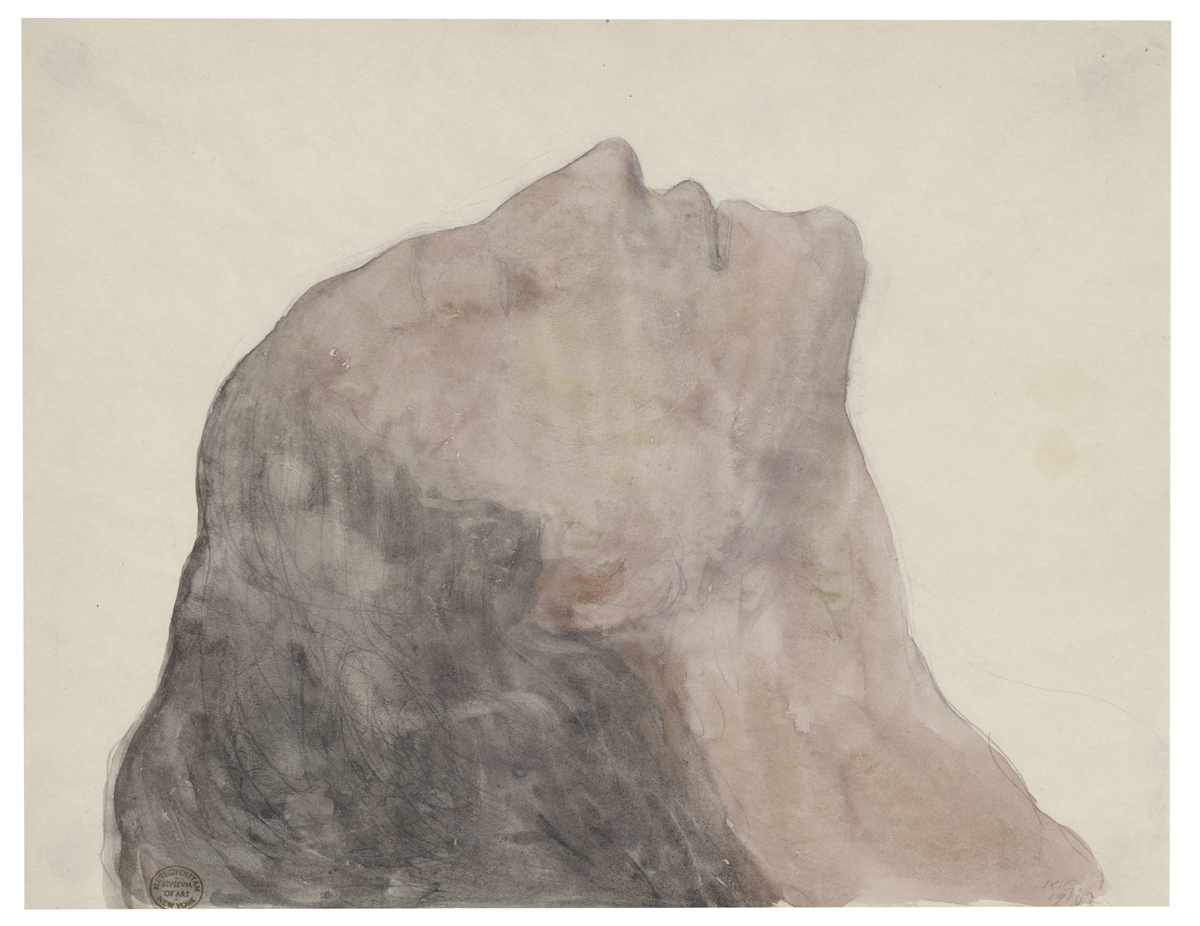

Kahlil Gibran, Towards the Infinite, 1916. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 8 3/8 × 11 inches. Courtesy Art Resource. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Despite his strategic self-fashioning, Gibran’s focus was not really on an East/West divide. His art indicates a desire to resolve binaries, to unify—to be spirit in the land; to be with his mother, Kamila; to be with God; to be whole after so long being split. Kamila passed away, still young, in 1903, shortly after the deaths of his older brother and younger sister. In 1916, Gibran made an eerie watercolor-and-pencil portrait of his mother at the moment of her death, Towards the Infinite. In her catalog essay, Lenssen interprets the work as capturing “with moving pathos the artist’s anxiety around survival . . . his impulse to mythologize precarity,” its solitary, attenuated visage “a membrane between presence and loss.”

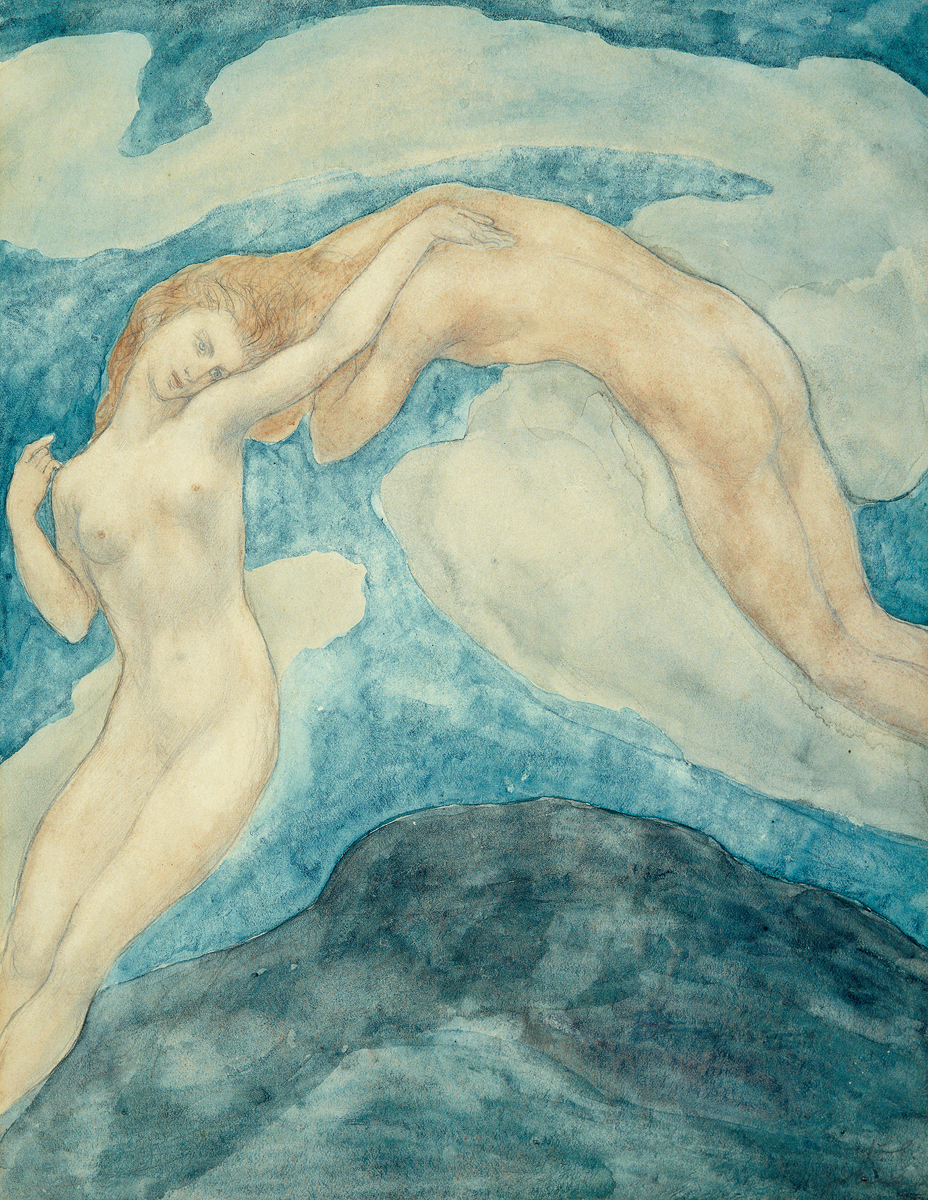

Kahlil Gibran, The Summit, ca. 1925. Watercolor and pencil on paper, 11 × 8 1/2 inches. Courtesy Telfair Museum of Art. Photo: Erwin Gaspin.

Towards the Infinite is on Agawam bond typing paper, sturdier than the flimsy stock Gibran typically chose in the first half of his career, so the downward strokes of mottled watercolors are contained within the penciled silhouette of the funeral-mask-like face. In other drawings from this phase, executed on thin, delicate, uncoated typing paper technically unsuited to his methods (as Lenssen points out), his watercolors bleed haphazardly across the drawn figures and pool into the vacant space surrounding them, dissociated from the graphite volumes they are ostensibly meant to model, as if two different works were layered on top of each other. Later, in the 1920s, like in the series of twelve he executed for The Prophet, the watercolors take over the page completely, so that human forms blur into landscapes, flow into one another. They are so fragile—but their lithographic reproductions, Gibran knew, would extend their lives forever.

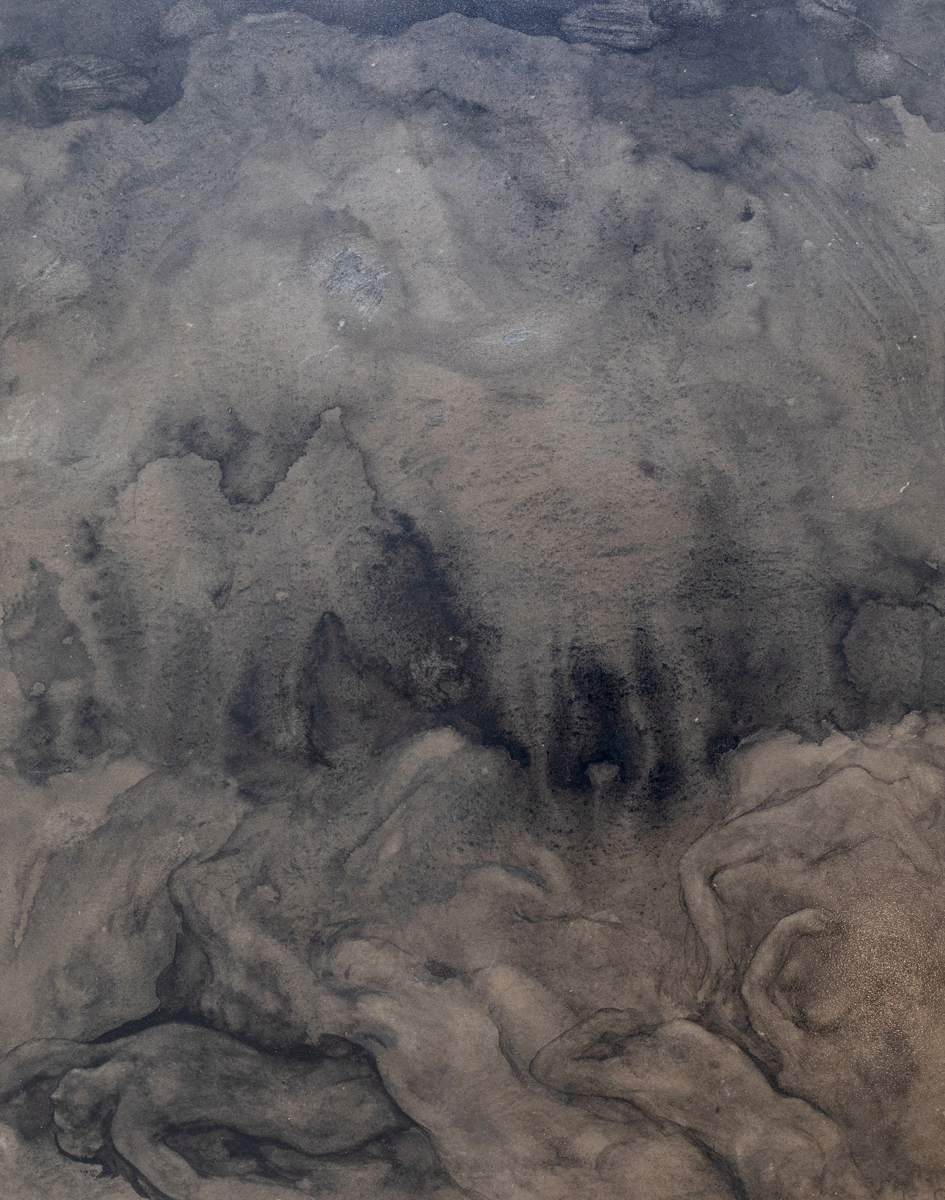

Kahlil Gibran, Human Figures Spread Out Below a Dark Landscape, 1930. Wash drawing, 14 × 11 inches. Courtesy the Gibran National Committee.

Gibran’s longed-for celebrity swelled after 1923. By then, his family was gone; the country he was born in no longer existed as such; his connection with his mother tongue had been severed; he could only be other than himself in his adopted country. In his Greenwich Village studio, he would hold on to his meteorite at night, clutching it in his hands while he slept, as if comforted by its solidity, as if fearing it might disappear anyway. He died, age forty-eight, in 1931, of the effects of alcoholism. One of the last works in this show, Human Figures Spread Out Below a Dark Landscape, is from the year prior. Its monochromatic picture plane is almost entirely abstract—rolling forms of felled bodies are barely visible at the bottom edge, beneath grisaille wash that erratically reels, muddles, transfuses; some areas look like peeling skin. It is his most lonesome work, and his wildest.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.