Elvia Wilk

Elvia Wilk

For a project merging two bodies into one, questions about binary structures and power dynamics.

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica.

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, curated by Benjamin Tischer, Pioneer Works, 159 Pioneer Street, Brooklyn, through July 10, 2022

• • •

Genesis P-Orridge first met Lady Jaye Breyer in 1993 at a Manhattan BDSM dungeon called the Whip Shack, where Lady Jaye, a nurse by day, was working as a dominatrix. It was love at first sight. When the couple moved in together nearly two years later, they commemorated their love with a day-long ritual intended to symbolize their “rebirth as newborn babies, twins, two halves.” First, they tenderly shaved every hair from each other’s bodies, then spent twenty-three hours on the floor of their apartment cuddling in the fetal position, wearing adult diapers.

This more or less marked the beginning of what they called the Pandrogyne project, which would continue until—and beyond—their deaths (Lady Jaye in 2007, Genesis in 2020). Its aim was the total merger of their formerly distinct selves into the creation of a single, genderless, “angelic” being known as Breyer P-Orridge. The transformation was not metaphorical. On Valentine’s Day in 2003, the two got matching C-cup breast implants, the first of what would end up being twenty-three plastic surgeries, with the goal of making them appear identical, and also to uncouple their identities from any notion of binary gender. In the words of their 2003 “Pandrogyny Manifesto,” repurposed now for the title of an exhibition at Pioneer Works, “we are but one.”

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Breyer P-Orridge, Touching of Hands, 2016.

The exhibition, curated by the artists’ longtime gallerist and friend Benjamin Tischer, offers a view into this Gesamtkunstwerk through self-portraits, collages, photos, and videos that chronicle the process and thinking behind it. The show also contains what might be termed relics—bodily matter, a bronze replica of Genesis’s arm—and a shrine containing small artworks, ephemera, and objects Genesis owned. The shrine was built specially for the space by one of Genesis’s daughters (from a previous marriage), Genesse, who loosely modeled it after the Buddhist dome-like stupas she and her father visited while traveling in the Himalayas. There are a few other references to non-Western spirituality, but the iconography—and attendant self-mythology—throughout the exhibition is remarkably biblical. The result is as much hagiography as art show.

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica.

The most iconic images on view are also the most graphic. Polaroids, photographs, and collages document bruised faces in the aftermath of nose jobs and cheek implants, stents and tubes draining fluid from incisions, and piercings and brandings on skin. There is a twinge of body horror, but the brutality is moving and its depiction vulnerable. The pictures telegraph a clear message: this is the extent to which they were willing to go.

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica.

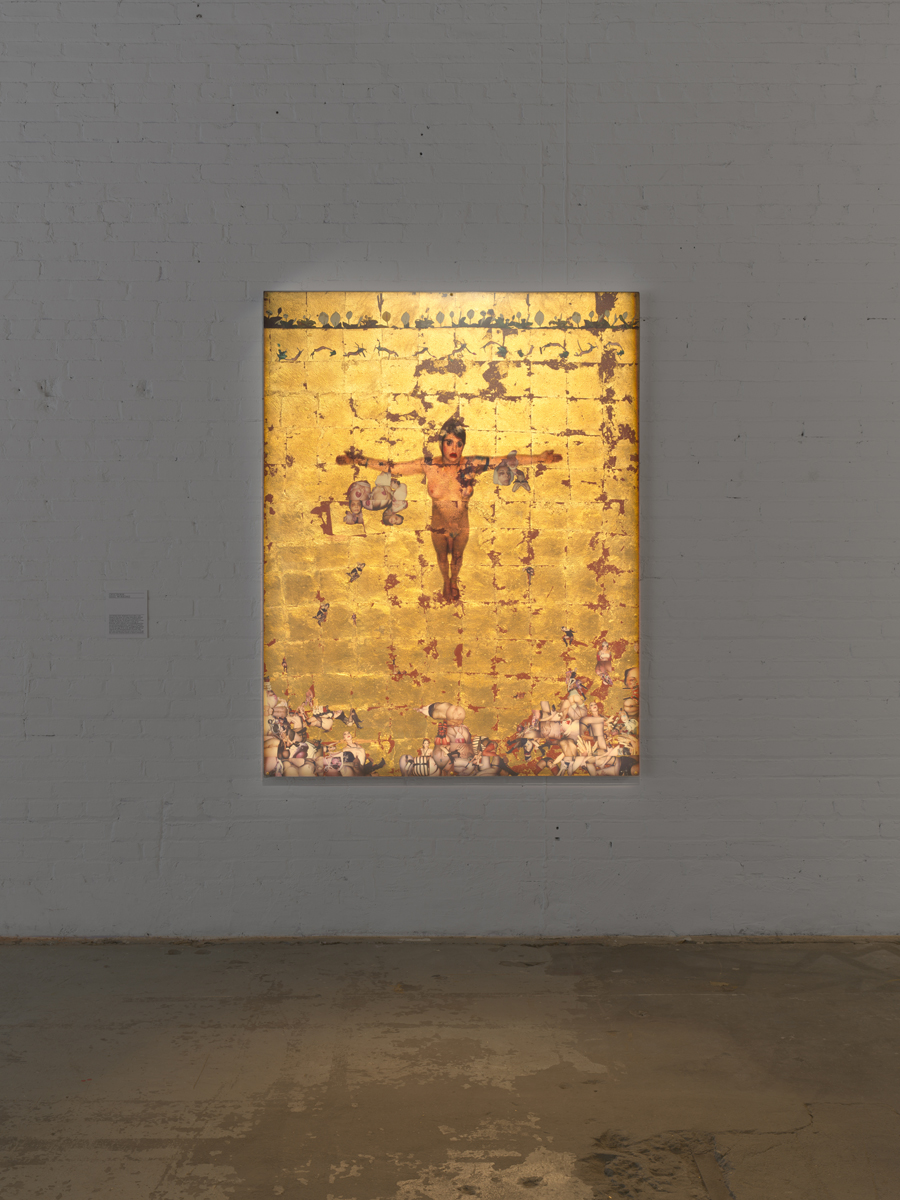

Near the shrine, a large collage, Cruciform (Sigil Working) (2005), shows Genesis with arms spread in a Jesus-T on a gold-leaf background, surrounded by clippings of pictures of pandrogynous body parts. The idea of collage was key to Genesis, who first met William S. Burroughs in 1972 and often cited the author’s well-known cut-up method as a central inspiration for he/r life’s work. To Genesis, the cut-up body of the Pandrogyne was the ultimate extension of the cut-up tactic as previously applied to word, image, and sound.

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Breyer P-Orridge, Cruciform (Sigil Working), 2005.

Like other prominent body hackers of the 2000s, such as Orlan and Stelarc, Breyer P-Orridge believed advances in the medical-industrial-pharmacological complex were part of a natural evolution of humankind that would allow everyone to someday escape meatspace—bodies being what Lady Jaye called “cheap suitcases” for consciousness. In some ways this presaged more recent theoretical work that frames the body as a natural-artificial construction, or that promotes appropriating medical technology for one’s own desires, such as that of Paul B. Preciado or the collective Laboria Cuboniks.

Breyer P-Orridge mostly referred to themselves with the pronoun “we.” But the extent of the “we” can be hard to locate in the exhibition. Genesis is the one posing like Jesus, Genesis is the name stamped on several of the collages. If one is to take the Pandrogyne premise at face value, it shouldn’t really matter which body is depicted or whose name is in the signature; but from the perspective of the art apparatus, authorship matters very much. Perhaps this imbalance of representation and attribution simply speaks to the limits of what cultural production allows and accounts for, but perhaps it also speaks to the contradictions at the core of Breyer P-Orridge.

By the time s/he met Lady Jaye, Genesis had long been a cult figure. S/he cofounded the UK art and performance collective COUM Transmissions in 1969, and fronted the influential proto-industrial noise bands Throbbing Gristle in the ’70s and Psychic TV in the ’80s. In response to a COUM Transmissions show (Prostitution) at the ICA London in 1976, which included things like porn and rusty knives, a Tory member of Parliament was quoted as saying, “these people are the wreckers of civilization.” Genesis gleefully took statements like these as validation of the work’s transgressive power. Throughout Genesis’s career, the desire to be a provocative outsider jostled with a desire for historical recognition. This problem has plagued protagonists of countercultures for a century, but it gains an extra complication given the self-stated values of pandrogyny—total equality, oneness, and sharing—and the proposition that body and name are arbitrary signifiers.

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Breyer P-Orridge, Stations ov thee Cross, 2003.

In a 2017 memoir, COUM Transmissions cofounder Cosey Fanni Tutti described Genesis as physically and sexually abusive. Another member said that Genesis was domineering and took credit for others’ creative contributions. P-Orridge denied all allegations, and the media has not given them huge attention. But I find it’s hard to forget this information once you know it, especially while looking at pictures of cut-up bodies. I want to believe in the coherence of the “we” in We Are But One. Yet given the art world’s expertise in passing off abuse as eccentricity or as the unavoidable fallout of genius, I feel uneasy in the presence of the work, and it’s not because I’m a scandalized Tory MP.

In he/r own memoir, published posthumously in 2021, Genesis explained: “Pandrogyny is not about defining differences, but about creating similarities. Not about separation, but about unification and resolution. Difference is the core problem.” Another social theorist might argue that difference is exactly what is required for erotic love, not sameness; that the existence of boundaries is what creates the site of desire—and that maintaining the integrity of the self even during the subsumptive experience of love is where the political, even radical, potential of intimacy lies. While Breyer P-Orridge saw the “either/or” binary structuring much of Western society (not only gender but also race, class) as the basis for oppression, one could argue the reverse, that erasing difference offers a cover for more insidious types of repression and control.

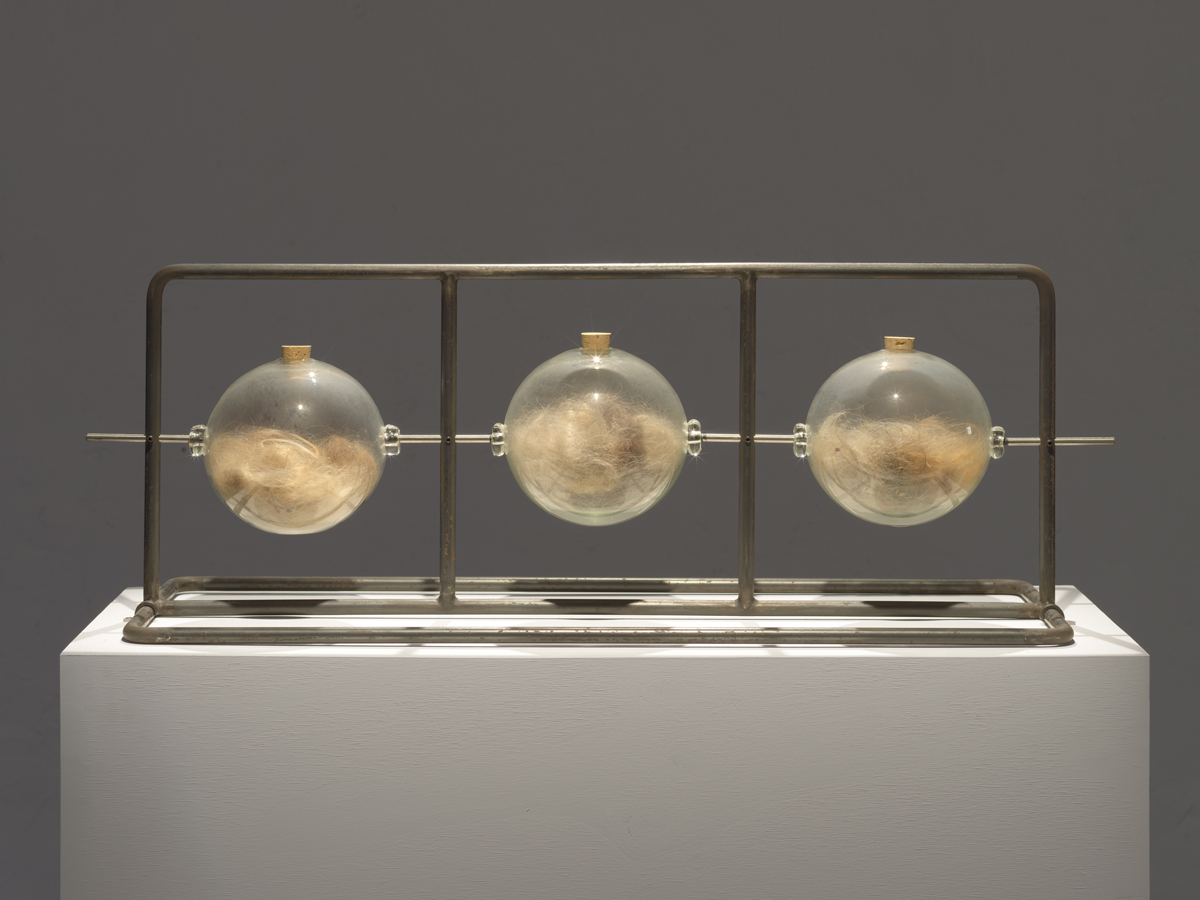

Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, installation view. Courtesy Pioneer Works. Photo: Dan Bradica. Pictured: Breyer P-Orridge, Alchymical Wedding, 1997–2012.

One dramatically spotlit work, Alchymical Wedding (1997–2012), consists of a steel frame with three blown-glass globes holding a collection of Breyer P-Orridge’s hair, skin, and fingernails. I find this piece, which is quite beautiful in a steampunk way, to be a microcosm of pandrogyny’s contradictions, ironies, and ambivalences. In he/r memoir, Genesis wrote that the art world is “a service industry to the rich,” and “it’s no mistake that art becomes valuable after an artist is dead.” And of the body itself: “There’s nothing sacred there. Nothing.” So, if the body is an irrelevant husk we are trapped in on the way to higher consciousness, and the art world is a bullshit place for rich people, why preserve fingernails for posterity? I wonder whether Breyer P-Orridge might respond by saying these things are not mutually exclusive: you can aim to transcend the body and also recognize the power of the body, and you can want to destroy the system while also wanting to be validated by it. Genesis could swallow this pill whole. Not everyone can.

Elvia Wilk is a writer living in New York. Her work has appeared in publications like frieze, Artforum, Bookforum, the Atlantic, Granta, the Baffler, n+1, the White Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is currently a contributing editor at e-flux Journal. Her first novel, Oval, was published by Soft Skull in 2019, and a book of essays called Death by Landscape is forthcoming in July 2022, also from Soft Skull.