Rahel Aima

Rahel Aima

The artist offers her vision of desifuturism.

Chitra Ganesh: Her garden, a mirror, installation view. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle. Image courtesy the Kitchen.

Chitra Ganesh: Her garden, a mirror, the Kitchen, 512 West Nineteenth Street, New York City, through October 20, 2018

• • •

It’s the late nineteenth century in the British Raj. In my colonial-tropical fantasy it’s a swampy, starry night. A fancy begum, an aristocratic lady, is reclining in a cane-and-Burma-teak easy chair. Her name is Sultana, she wears filmy whites and her mogra-scented hair is unbound. She is, in her own words, “thinking lazily of the condition of Indian womanhood” when suddenly it’s morning, and her friend Sister Sara materializes to take her on a whirlwind walking tour of Ladyland, a place that sounds like it should be sponsored by Kotex but isn’t.

Our heroine frets because she observes purdah, the religious segregation of genders. But in Ladyland the roles are reversed. It is men who now live shut away indoors, for they are like wild animals, untrained, untrustworthy. Boys will be boys, so lock them up! Instead, women run the show with the help of solar power and climate engineering. There are no quarrels, pollution, war, accidents, or epidemics. There’s plenty of time for leisure: embroidery and botany abound. The whole country is essentially a utopic and arguably rather queer garden and you can probably imagine how it ends. It was all a dream, but Sultana is woke now.

This is Sultana’s Dream, a technofeminist sci-fi novella published in 1905 by Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. And you, you’re reading the story because you’ve picked up a newsprint copy from a pile in the middle of the Kitchen’s main gallery, which currently houses an exhibition of new work by Chitra Ganesh. Or perhaps you’re hearing it narrated from one of four ceiling-mounted speakers.

Chitra Ganesh: Her garden, a mirror, installation view. Photo: Jason Mandella. Image courtesy the Kitchen.

Her Garden, a mirror is a spare, dark show, all but one of its dark purple walls adorned with a constellation of dimly lit linocuts. In them, we find Ganesh’s familiar vocabulary drawn from filmi pop culture, Hindu and Buddhist iconography, and Indian comic books, all with a generous dose of DeviantArt. The prints are fine. They’re attractive; nice, even. So is Manuscript (all works 2018), where neon animations (roses, satellites, Bengal School–style eyes) spin over a huge aluminum and raw-silk hand, whose mehendi-like patterning is reflected in the large chalk drawings elsewhere in the space. So, too, is Totem, a monumental sculpture studded with many cyborg femme-leaning faces who sport VR goggles and circuit board patches. But the visual vocabulary of these pieces feels generic to me, an amalgamated pastiche of boilerplate South Asian references repackaged for a white gaze.

Chitra Ganesh: Her garden, a mirror, installation view. Photo: Jason Mandella. Image courtesy the Kitchen.

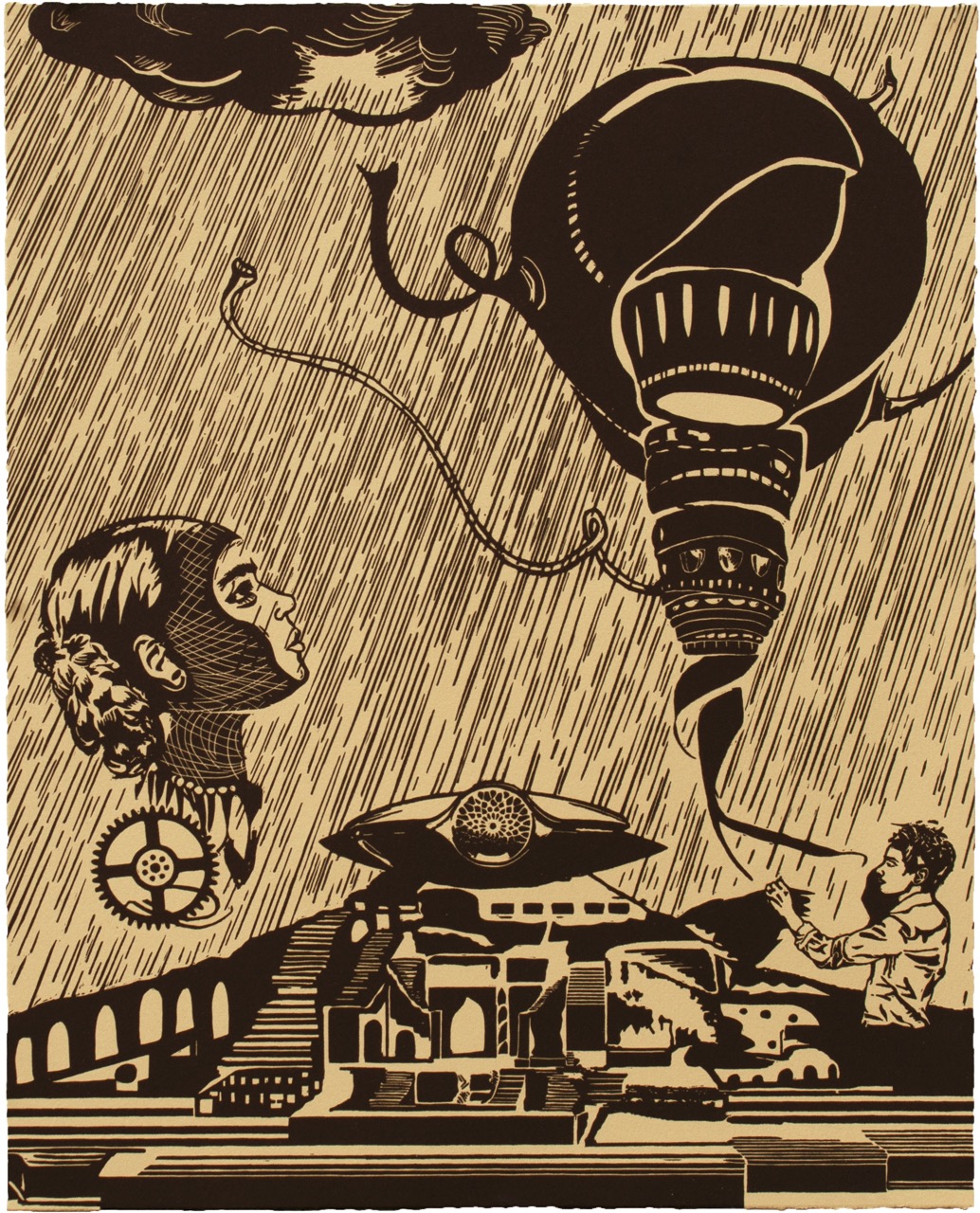

Returning to the linocuts, while saris, bindis, and chappals emphasize the South Asian setting, protest scenes, cogwheels, and blazing fists suggest North American radical culture. And is that Ladyland’s rainmaking balloon, its flying cars, Sultana snoozing by an open window? In Ganesh’s fantasy, the heroine lounges in the same wood-and-wicker chair I envisaged, but she is younger and bespectacled, and her room boasts cracked walls and busy tilework. Cyborgific cosmic beings that seem half god, half alien extend Hossain’s text into deep space. Even as they reach across a century for Ladyland, the characters in Ganesh’s reveries are decidedly contemporary.

Chitra Ganesh, Water Storage, 2018. Linocut print. © Durham Press.

When we imagine ourselves in the future, it tends to be in one of two ways. Two currents in contemporary art are Gulf and Sino futurism. Like their early-twentieth-century Italian predecessor, they fetishize technology and speed, and propose frankly authoritarian ethnonationalist futures. Afrofuturism, and by extension indigenous and Chicanx futurisms, meanwhile turn to science fiction in response to a dearth of representation. Strategies include projecting oneself into the future as a means to emancipation in the present, and restaging the moment of colonial encounter that ended in occupation, slavery, or genocide. Even as they might pick out specific identities such as being black, or Native or Mexican American, these futurisms are decidedly pan-Global South, featuring everyone that Curtis Mayfield might have referred to as “darker than blue.” The speculative futures of the Indian subcontinent have—and continue—to range between the two.

In coining the term desifuturism, I envisaged something of the latter kind, swapping out Afrofuturism’s Egyptian mythology for Hindu. “Scifi mahabharata; cyborg kali?” a 2012 tweet of mine asked. Desifuturism’s transhumanist utopia would sweep out the last vestiges of casteism and dream of a future in which Partition never happened. Essentially it was Afrofuturism surgically transposed to South Asia, but with what I now see as a problematic emphasis on appearance over function.

Chitra Ganesh: Her garden, a mirror, installation view. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle. Image courtesy the Kitchen.

Perhaps this is why I was most charmed by Ganesh’s video installation How we do. It jettisons aesthetics in favor of praxis, considering how this feminist utopia might actually function, and how generosity and collectivism combine to build community. Two compilations of multilingual how-to videos play simultaneously on CRT monitor stacks: how to do a headstand, how to make a clay wedge, how to cook the Pakistani delicacy of bittergourd and mutton, how to mix North Indian bhangra tracks (featuring DJ Rekha), how to cover up a tattoo. Yet interspersed are feel-good newsreels about women driving trucks, or working as India’s only female mechanic. Getting excited about women taking on traditionally male jobs is feminism as sanitary pad commercial, the kind that pours the blue liquid instead of blood and can’t quite believe the gender roles these hijabi women are breaking: Bangla surf girls and Afghan skaters! Female truck drivers and car mechanics! Is there really anything radical about “brown girls do it well” feminism?

Still, there are merits to Ganesh’s project, particularly at this historical moment, with its virulent rise of Hindu nationalism. Working against cultural phenomena like the comic-book series Ramayan 3392 AD, which restages ancient Hindu texts several millennia in the future, and the emergence of Indofuturism, which dispenses with the rest of the subcontinent altogether, Ganesh is to be commended for her mix of multiethnic and multi-religious references, for envisioning a desifuturism that includes more than just Hindus.

Rahel Aima is a writer from Dubai currently based in Brooklyn. She was founding editor-in-chief of the experimental publishing practice THE STATE, and is special projects editor at New Inquiry and a correspondent at Art Review Asia. She is currently at work on a book about color and futurity.