Rumaan Alam

Rumaan Alam

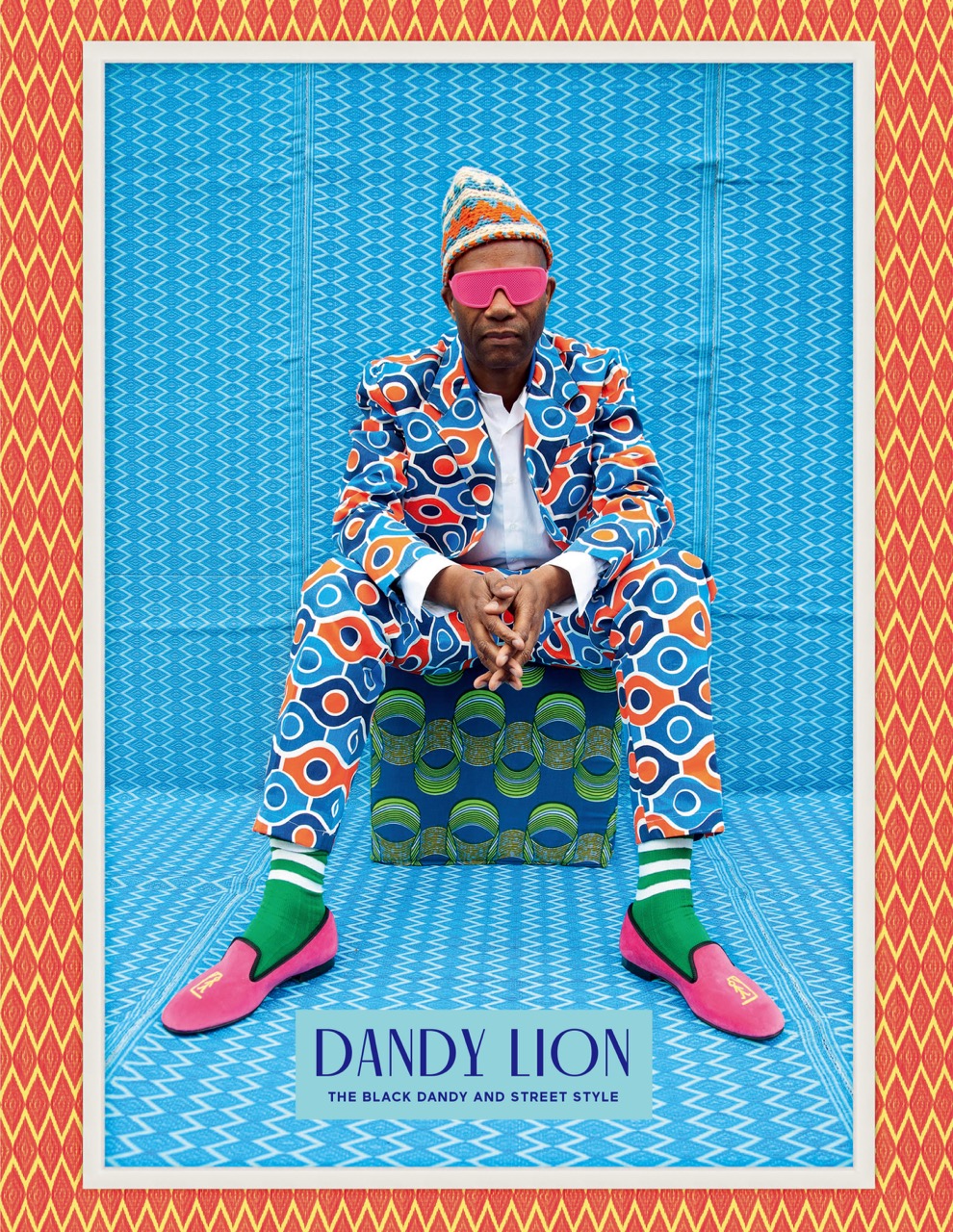

Shantrelle P. Lewis’s photo-filled book revels in sartorial splendor.

Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style, by Shantrelle P. Lewis, Aperture, 175 pages, $35

• • •

“Black is Beautiful” is a persuasive bit of sloganeering—far more effective, I think, than the vague “Resist/Persist” of the current moment. If “Black is Beautiful” can claim as its heir Black Lives Matter (in that they’re both a riposte to a culture that declares otherwise), there’s something chilling in considering where the decades have taken us: from talking about beauty to talking about lives.

Still, you might argue that they’re one and the same. In her introduction to Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style, a trim and colorful volume by Aperture, the curator Shantrelle Lewis writes:

It’s true that historically, dandyism has always been outside the traditional tropes of masculinity—queer, in a sense—but dandies also threatened the existing class structure by dressing up. A Black man employing this strategy is even more radical and subversive. . . . He defies monolithic understandings of what it is to be a man—particularly a Black man—through a colorful and complex dance between race, class, gender, power, and style.

In a moment where slapping a #resist on your latest communiqué counts as activism, it’s worth remembering that for many simply existing is a political act, or one of bravery anyway. Years ago, I saw a lad on a late-night subway, in unremarkable jeans/T-shirt and towering Louboutin heels. Surely that skinny teen was one of the toughest people I’ve ever seen; surely his insistence on being seen was a kind of triumph.

Dandy Lion is an ongoing curatorial endeavor, a hodgepodge of portraiture (some commissioned), fine art photography, archival snapshots, and contemporary street-style pictures, which began in 2010 at a pop-up gallery in Harlem, traveled the world, and has now congealed between two covers. The book also contains short profiles of notable dandies, artists, and movements, both historical and contemporary.

Lewis is a helpful guide. She offers context on Jamaica’s 1960s-era youth in revolt the Rude Boys, with their skinny ties and throwback hats, and the Congolese community of impeccably turned-out men known as Les Sapeurs, who revere designer clothes. While those subcultures are mainstays of the fashion designer’s inspiration board, Lewis casts her net wide: the book covers a Ghanaian Tumblr movement, a South African league of competitive dressers, various blogs, designers, and so on.

Though Lewis dubs the dandy queer, in the project’s early incarnation it focused on heterosexual men, “to challenge homophobic assumptions about what types of men wear fitted clothing and pink shirts.” Now, the dandies herein are gay, straight, male, female, cis, trans, confidently not conforming, every one of them insisting that we see them.

Omar Victor Diop, Alt + Shift + Ego, 2013; from Dandy Lion. © Omar Victor Diop, courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A.

To be a dandy is a commitment. We’re talking bow ties and boaters, suspenders and striped socks, opera scarves and overcoats, pocket squares and patent leather shoes. The dandies in this book must know their barbers well. The tailoring is always flawless, the color palette is often adventurous. There’s a spectrum of style on display: sometimes it’s historical reenactment (of the postwar Ivy League heyday, the Jazz Age, or back further to the downright Edwardian) and sometimes it’s thoroughly modern sharp-cut suits in Dutch wax prints. The title is apt; a group of lions is called a pride.

Daniele Tamagni, from the series Gentlemen of Bacongo, Brazzaville, Congo, 2013; from Dandy Lion. © Daniele Tamagni.

Putting on a dress doesn’t make you a queen (ask any college boy the day after Halloween) and dressing up doesn’t make you a dandy. The impulse isn’t about traveling to some imagined halcyon day when men wore hats and black undergrads couldn’t get lunch at Woolworth’s. “The Black dandy,” Lewis writes, “is a social engineer who employs sartorial instruments to articulate his own masculinity and, in essence, his own humanity.” Talk about #resist.

Lewis declares the Black dandy (the capital B is her flourish) a trickster figure, and shows how this figure pops up throughout time, across the globe, as man and even occasionally as woman, as tricksters are wont to do. Of course, it’s the book’s pictures that do the heavy lifting, every one worth poring over. There are fashion magazine spreads as well as fine art projects like the electric Hassan Hajjaj image on the book’s cover (less a portrait than a Warhol-flavored confection that is a collaboration between the artist, his subject, and a tailor). There are profiles and portraits of designers like Michael Tetteh Nartey and Ozwald Boateng and pop culture figures like singer and actress Janelle Monáe and athlete Amar’e Stoudemire. To my mind, the real delight is encountering folks like the aptly named Dandy Wellington, who leads a swing jazz band (really) and has (of course) thousands of Instagram followers.

Rose Callahan, Dandy Wellington at the Seersucker Social, Washington DC, 2011; from Dandy Lion. © Rose Callahan.

It’s well understood, now, how the fashion iconoclast can end up influencing the fashion industry, and how that cycle of influence has accelerated in this connected age. Corporate forces have a way of coopting black creativity: using breakdancing to sell Mountain Dew, or borrowing “on fleek” from Kayla Newman, the teenager who coined the phrase. Thus I was relieved to read here that the young men behind a style blog called Street Etiquette have set up shop as a branding agency. Undermining “monolithic expectations of what it is to be a man” is all well and good; so too is getting paid.

Curators often leach the fun out of fashion; however serious a text this is, it is primarily a straightforward celebration of the delight that strikes me as an inherent component of dandyism. It’s beautiful, the book, but it’s also persuasive, seductive—who wouldn’t be seduced by all these gorgeous people?

Though painting is outside the project’s purview, I thought of Barkley Hendricks (specifically his 2016 Photo Bloke: a black man in pink suit, white shirt and pocket square to match). Hendricks rendered black men (himself included) as beautiful throughout his career; if it’s still all too rare to find blackness depicted on the gallery wall, to say nothing of blackness rendered as beauty, it’s commonplace on social media. What matters more: art or life?

Anyway, that’s what these tricksters are saying, isn’t it: that they are works of art, that black really is beautiful. Beauty, of course, is not salvation. In her introduction, Lewis reminds us that while “the suit can be a form of armor,” it is “not bulletproof.” Still, two things can be true at once: black lives matter, and so, too, does black beauty.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novel Rich and Pretty. His stories have appeared in Crazyhorse, StoryQuarterly, American Short Fiction, and elsewhere; his writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, the New Republic, and elsewhere. His novel That Kind of Mother will be published in 2018.