Domenick Ammirati

Domenick Ammirati

Vantage meets visage: a new show makes inquiries into rational systems and modes of presenting the self.

David Muenzer: Proxetics, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Dracula’s Revenge. Photo: Jason Mandella.

David Muenzer: Proxetics, Dracula’s Revenge, 47 Canal Street,

New York City, through June 20, 2022

• • •

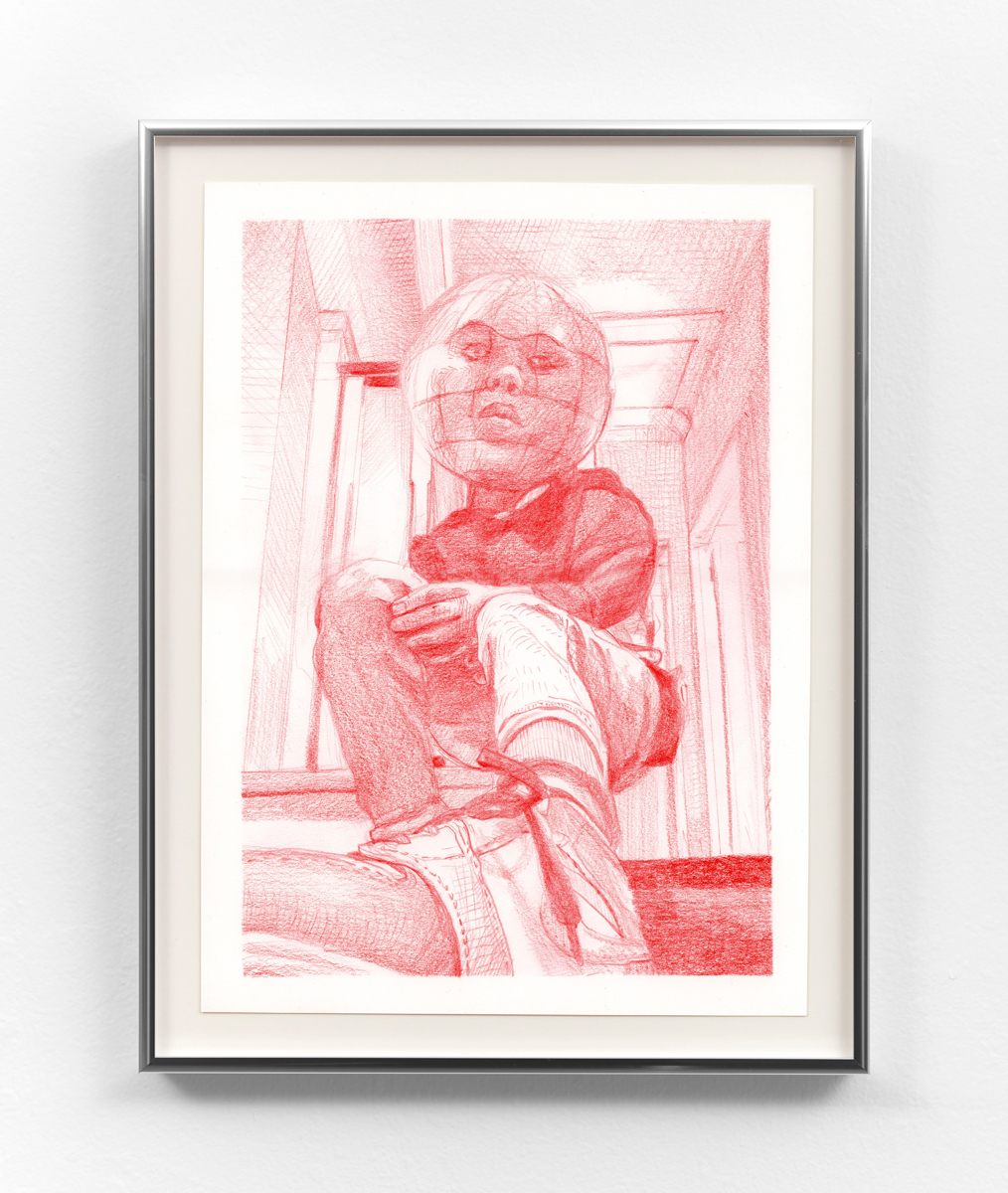

The marquee motif of David Muenzer’s New York debut may strike you as almost goofy: in one painting and a suite of vibrant, deft figurative drawings in red pencil, he has transformed the head of each of those depicted into a globe, inscribed with contour lines as if out of an art textbook. The figures vary in demeanor and garb, as do the scenes they inhabit, and their too-small faces fit onto the spheres awkwardly—recessed like depressions on an underinflated basketball, poking out like Groucho Marx schnozz-and-glasses. The most contemporary of them confronts us in a selfie, phone propped improbably on the floor with their Air Jordan Mid thrust up practically against the lens. Another meets our gaze languorously as she reclines on a carpeted floor. A third, who seems a child or young adolescent, poses awkwardly as she examines her image on a laptop screen: the twenty-first century’s mirror-stage, checking one’s looq before a video chat. The visitor to the exhibition takes all this in while standing atop one more work, a gray industrial carpet patterned with pink, yellow, and light blue geometrical shapes. It depicts a conflict-themed tactical flowchart that flows nonsensically in every direction. A sample question: “How do you want to win?” One of the more cogent responses: “Making my opponent regret the life choices that led to this match.”

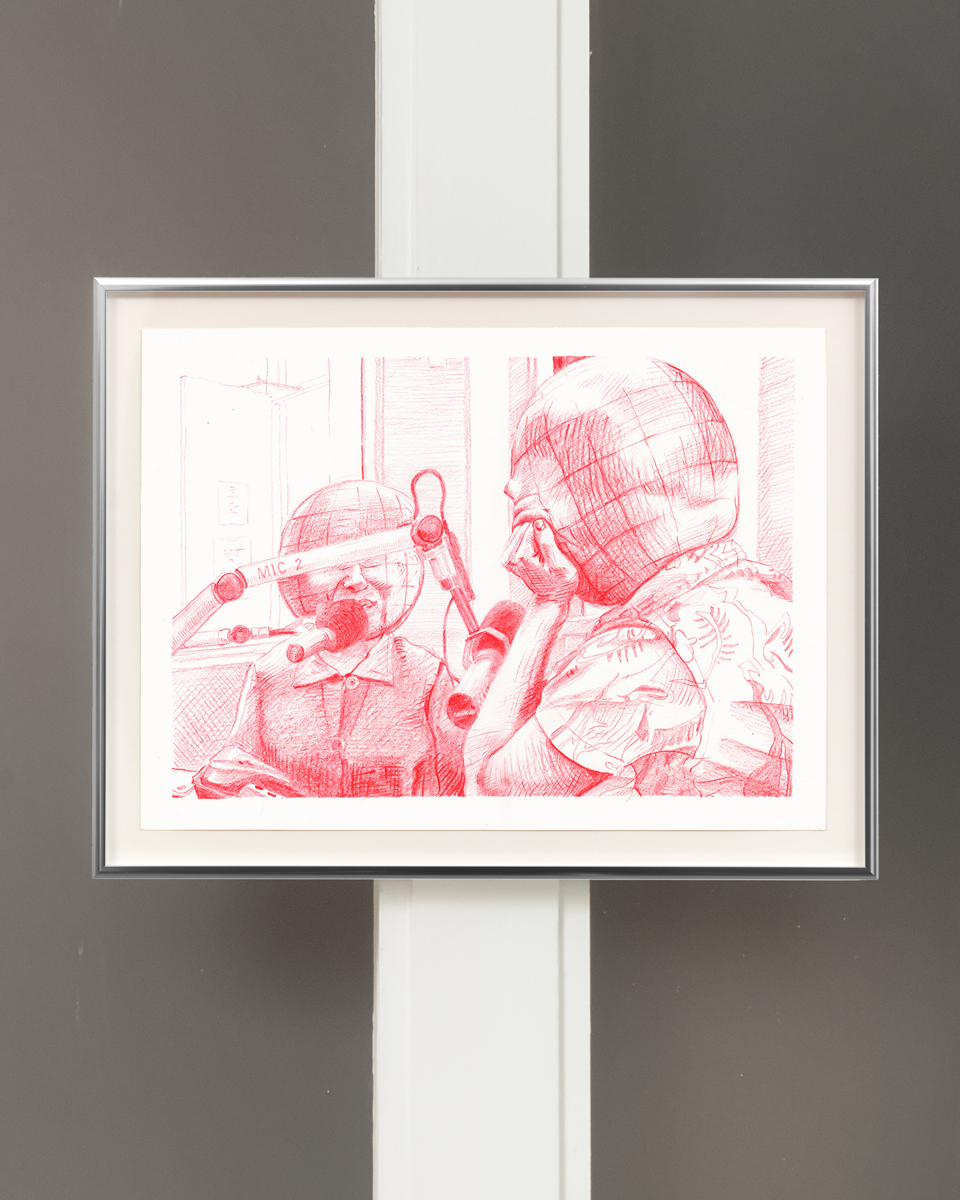

David Muenzer, Solo, 2021. Colored pencil on paper, 11 × 15 inches. Courtesy the artist and Dracula’s Revenge. Photo: Jason Mandella.

You gotta give it up to the guy, Muenzer: in a world of punchbutton signifiers, the show is pretty weird. As symbols go, the globe is more than a little overdetermined, so trying to interpret it, or anything else, in a simple fashion seems not the most urgent task at hand. By drawing his subjects with great care, the red pencil harking a bit to da Vinci’s red chalk, Muenzer establishes a tempo of slowness, a mood of deliberate looking and inquiry, with no pressure to arrive at a “meaning.”

David Muenzer, Solo II, 2021. Colored pencil on paper, 11 × 15 inches. Courtesy the artist and Dracula’s Revenge. Photo: Jason Mandella.

As a result, what resolves as one spends time surrounded on five sides by this hermetic array—which is mustered in a brand-new, Mondays-and-appointments-only shoebox gallery—feels rather much up to you. To me, the works capture fleeting formations in the recent history of visual modernity. The show is like a core sample of representational modes, extracting strata to a depth of about fifty years—or, counting the painting, a pastiche of Courbet, to a substratum back in the nineteenth century. If you take a close look at the prone woman gazing up ambiguously at her unseen photographer, for example, the carpeting beneath her suggests ’70s shag: we’re in the snapshot era, the democratization of analog photography. The girl posing in front of her laptop, meanwhile, evokes the recent past, when the digital shaping of one’s image—and the digital construction of one’s self—was still new rather than the water in which we all swim. The selfie is the product of our smartphone, social-media era, with the poser copping a characteristically pointless mean mug.

David Muenzer, Duet, 2020. Colored pencil on paper, 15 × 11 inches. Courtesy the artist and Dracula’s Revenge. Photo: Jason Mandella.

Another drawing shows two people talking in a radio studio, the diagonal of a mic boom slashing across one figure’s face, while the other props his chin on his hand and turns his back to us. I can only imagine the source to be a photo illustration for a magazine story, “artily” or just plain poorly composed. The setup seems to date to the later ’80s or ’90s. Perhaps it’s the Hawaiian shirt the interviewer wears; perhaps it’s the fact that those years mark the beginning of the talk-radio era, in which reactionary conservatism began to take over the American airwaves. Rush Limbaugh went national in 1988.

David Muenzer, Trio (The Meeting, or Hello!), 2022. Oil on linen, 52 × 72 inches. Courtesy the artist and Dracula’s Revenge. Photo: Jason Mandella.

The painting, meanwhile, is at first puzzling. It’s a reworking of the iconic The Meeting, aka Bonjour, Monsieur Corbet! (1854), wherein Gustave depicts himself meeting a collector and his servant in the countryside. Muenzer renders with some delicacy the wide-open composition of the original and its natural palette. But the three figures are like those in his drawings, limned in linear red and white, and they’re inexplicably lined up in a row, with the foregrounded artist figure throwing the other two globe-domes into eclipse. With this leap back to the mid-nineteenth century, Muenzer sets early modernism as a limit to his survey of visual modalities, and invokes a telling figure: Courbet, the realist painter par excellence, was an early fan of photography, and one of the first artists to commission photos of his works.

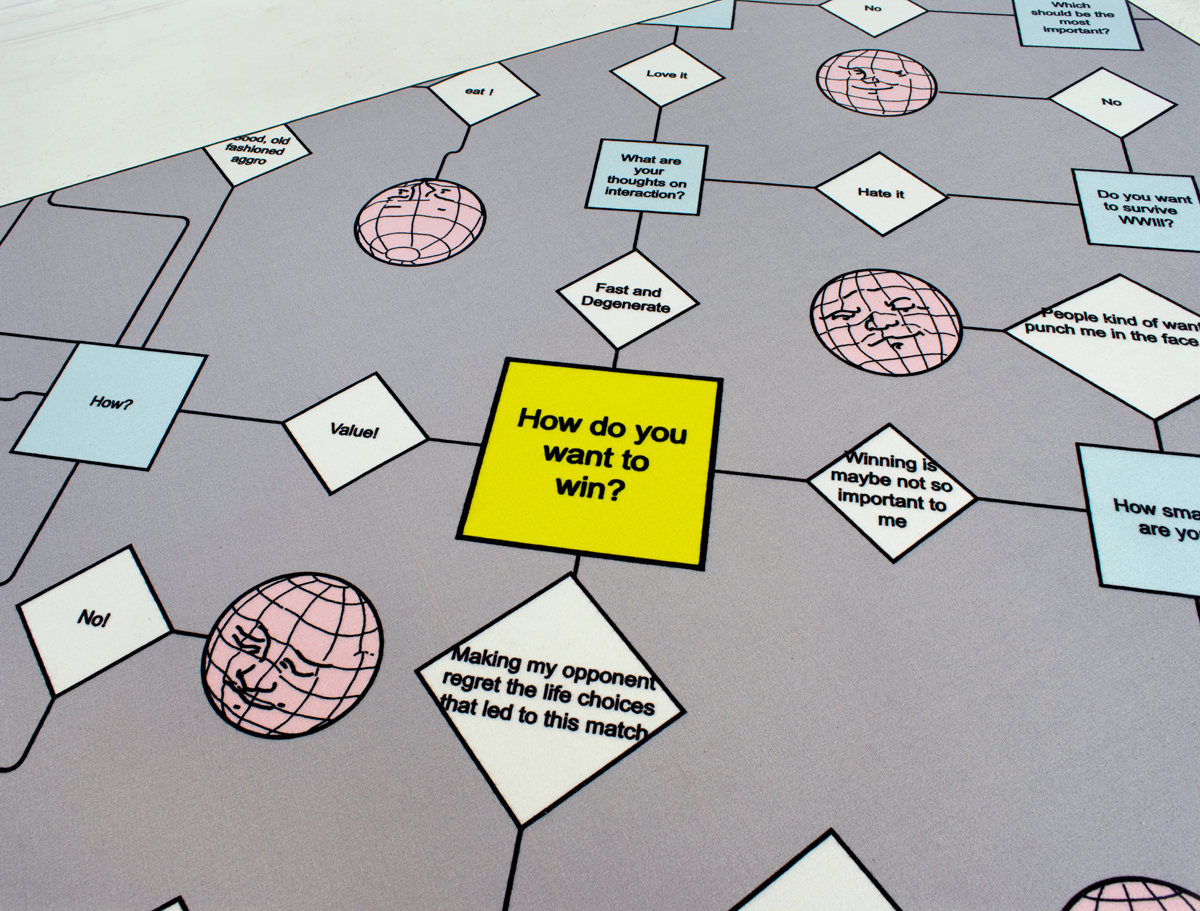

By unexpectedly surfacing photography also here, Muenzer makes the machinery of vision the exhibition’s root note. In modern times, vision is intimately connected to power; if you can’t take my word for it, take Foucault’s. Realism, as an asymptotic pursuit to ever-more-exactly capture the world, is ultimately a pursuit of control. Da Vinci, recall, applied his red chalk to both exquisite renderings of the human form and diagrams for machines of war. Today, the realism of Courbet is left in the dust of the French countryside; we’re increasingly accustomed to scraping away the visual in favor of what underpins its digital forms. That shitposty decision-tree carpet that lies underfoot, titled How to Compete (2020–22), represents sarcastic strategies for playing the card game Magic: The Gathering. Unlike an actual decision tree, which imposes a rationalizing flow of one choice into another, this one sprawls indefinitely and aimlessly, just a bunch of dopey questions and wiseass answers spreading toward every point of the compass. “How smarmy are you?” a sample node asks. Choices: “Not very,” “OK, a little,” “Winning is maybe not so important to me,” and “People kind of want to punch me in the face.” Decisions lead inevitably to dead ends where one is met by one of Muenzer’s globe heads with a sardonic, smug, or disapproving mien. The Enlightenment as final boss?

David Muenzer: Proxetics, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Dracula’s Revenge. Photo: Jason Mandella. Pictured: David Muenzer, How to Compete, 2020–2022. Dye sublimation print carpet, jute backing, 128 × 130 inches.

In the evolution of visual codes that Muenzer depicts, the decision tree occupies a hinge point. The form, which dates to around 1963, is a way to represent algorithms that emerges from early computer science. Decision trees thus represent a high-water moment for the optimist’s version of modernity as machines began to move toward autonomous behavior and “intelligence.” What Muenzer’s flagrantly moronic diagram captures, however, is the point we have reached in the present, stuffed to the gills with abstraction and quantification and sickened by it. The algorithmic way of conceiving thought, designed to structure and train machines, has come to circumscribe our way of thinking about ourselves: rational actors making rational choices. The effects are even more pernicious than the cult of Instagram that warps our views toward our own appearance. Perhaps we cling so desperately to selfies, perhaps we try like Muenzer’s poser to look so tough, because we don’t actually read ourselves through image; rather, we read ourselves through math—until the point at which rational actors become irrational and systems splay and mutate out of any control.

David Muenzer, Solo III, 2021. Colored pencil on paper, 11 × 15 inches. Courtesy the artist and Dracula’s Revenge. Photo: Jason Mandella.

In a final odd twist, Muenzer commissioned a linguistic anthropologist to write a text for the exhibition, available as a printed handout in the gallery. “We must accept and expect miscommunication and incomprehensibility,” the author, Edwin Everhart, writes. “Let uninterpreted language be a joy.” That let-it-all-hang-out tone is tempered, however: “Language is fun but it is not a toy. . . . we must support and share the labor of good interpreting and translating.” Subtlety is a casualty of context collapse; as thought turns into data processing and cripples the ability to conduct such labor, such play, we eventually lose the desire to access, interpret, to understand at all.

Domenick Ammirati is a writer and editor living in New York. He is a regular contributor to Artforum, and his writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including Art in America, frieze, Mousse, Los Angeles Review of Books, Dis, and exhibition catalogues for Josh Kline and Josephine Meckseper. In 2016–17, he served as an editor for documenta 14’s publications program in Athens and Kassel, and from 2009 to 2014 he was senior editor at the Guggenheim Museum.