Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Jane, meet Truman: the direct cinema of Robert Drew highlights an expansive nonfiction film festival.

Angelo Borgien and Modeste Landry in Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer, 1961. Image courtesy Film Forum.

“60s Verité,” Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City, through February 6, 2018

• • •

The history of cinéma vérité—“truthful cinema”—an up-close documentary style that dates to roughly 1960 and was made possible by lightweight, synch-sound cameras, inverts an idiom. Documentaries aren’t so much the truth of the matter—impartial records of the real, the actual—as they are the matter of the truth, that ever unstable concept. The animating principle behind this nonfiction methodology varied depending on where it was practiced. The French, led by anthropologist and filmmaker Jean Rouch, called attention to the ways that the presence of the camera affected how subjects behaved in front of it. That premise is demonstrated in the foundational Chronicle of a Summer (1961), co-directed by Rouch and Edgar Morin, in which a wide variety of Parisians are asked a simple, profound question: “Are you happy?” In contrast, the American cohort, headed by Robert Drew, stressed that the “invisibility” afforded by the new, portable equipment allowed for the capturing of objective reality. In its iteration on this side of the Atlantic, the documentary mode lost two acute accents, thus becoming cinema verité, and gained a synonym: “direct cinema.”

Film Forum’s vast “60s Verité” series brings together more than fifty titles, including several films by Drew and those who were part of Drew Associates, his independent documentary company; the theater is also hosting a companion nine-film Rouch retrospective. The expansive offerings reveal how often the notions of “truth” and “objective reality” were upended during a tumultuous decade.

An editor and writer at Life magazine, Drew founded Drew Associates in 1960, with the goal of transforming nonfiction films from the staid didacticism epitomized by newsreels to a more dynamic mode of storytelling. This new form, the journalist declared, “would be reporting without summary and opinion; it would be the ability to look in on people’s lives at crucial times, from which you could deduce certain things and see a kind of truth that can only be gotten by personal experience.”

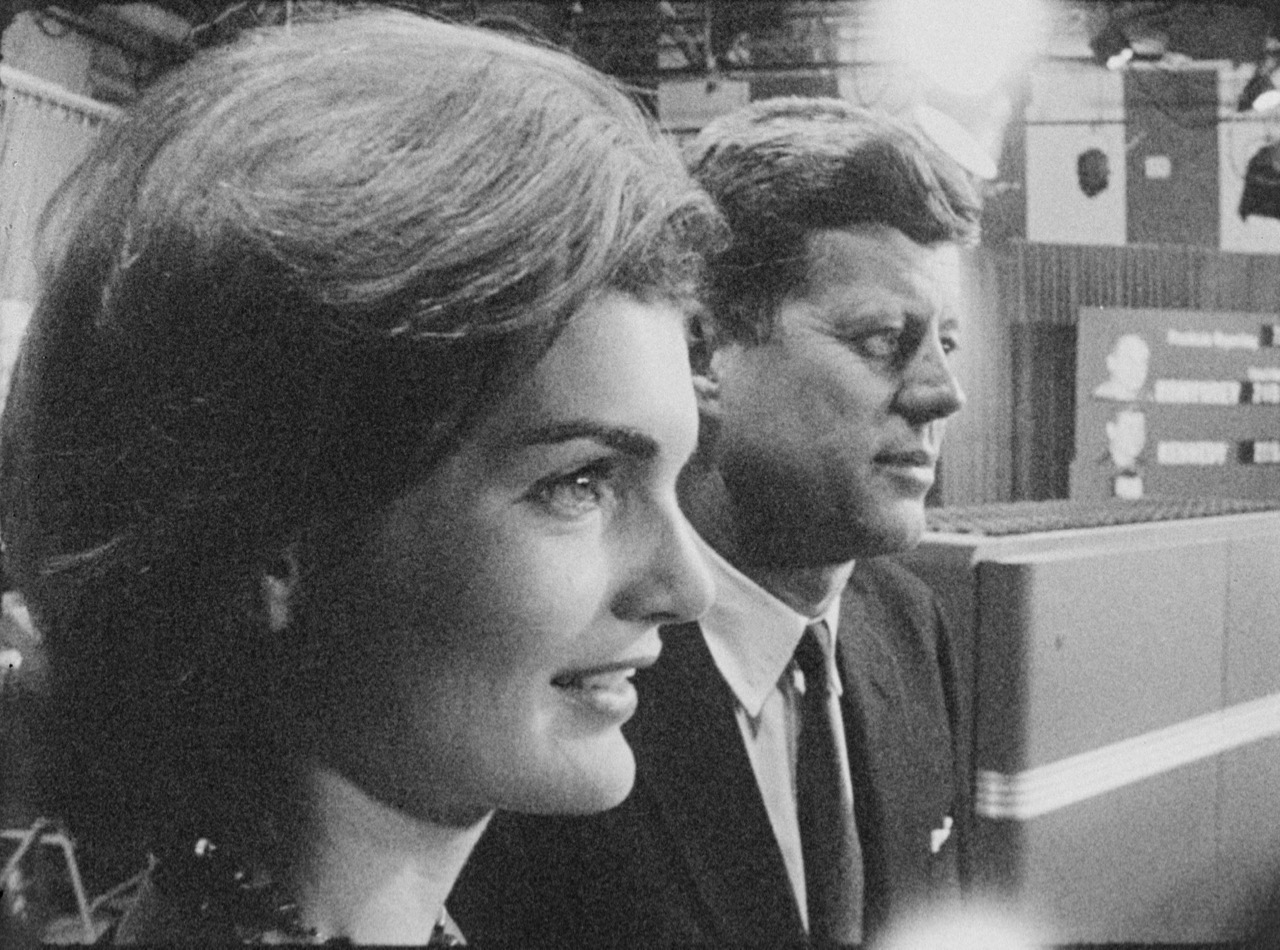

Jackie Kennedy and John F. Kennedy in Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker, and Albert & David Maysles’s Primary, 1960. Image courtesy Film Forum via Drew Associates.

Primary (1960), the landmark work of the Drew canon, provided viewers with unprecedentedly candid access to John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey as they vied for the Democratic nomination for president that year. The film is the inaugural of four Drew and company would make about Kennedy, the first direct cinema “star.” Two other documentaries (each under an hour) by Drew and others closely affiliated with him and the direct cinema movement endure as fascinating profiles of a different kind of celebrity. One tracks an actress (soon to be an icon) in the infancy of her career; the other shows a writer at the apex of his fame.

Jane Fonda in Robert Drew, Hope Ryden, and D.A. Pennebaker’s Jane, 1962. Image courtesy Film Forum.

Jane (1962), which Drew directed with Hope Ryden and D.A. Pennebaker, centers on the weeks leading up to the Broadway opening of a comedy starring Jane Fonda, then twenty-four and only two years into her vocation. The play, inauspiciously named The Fun Couple—about two honeymooners played by Fonda and Bradford Dillman—is savaged by theater critic Walter Kerr. The newspaperman is filmed rushing from the Lyceum Theatre on West Forty-Fifth Street to his office at the New York Herald Tribune to bang out his venomous review. The strained, antic romp closes the day after its premiere.

Fonda calmly reads Kerr’s pan aloud (“The only thing [The Fun Couple] proves . . . is that no matter what the circumstances, professional performers do not die of embarrassment on the stage”), at one point softly laughing. The words wound, but Fonda keeps her composure, admitting only, “It really is like needles.” That equanimity is also demonstrated in the first few minutes of Jane, as the actress withstands the outbursts of her director, Andreas Voutsinas, in rehearsals. His eruption of pique at Fonda is immediately followed by a kiss on the mouth—and an explanation from the off-screen narrator: “They’re friends and he dates her often.”

Jane Fonda in Robert Drew, Hope Ryden, and D.A. Pennebaker’s Jane, 1962. Image courtesy Film Forum.

Featuring many segments of the actress backstage in her dressing room, Jane gives a sense of cozy intimacy with its subject. She discusses, with an unseen interlocutor, the resentment she has felt from other performers, convinced that any of the handful of roles on stage or screen she’s received up to that point resulted not from her talent and hard work but from being Henry Fonda’s daughter. Jane offers an intriguing glimpse of public and private humiliation, of a neophyte’s determination to succeed. (A decade later, Fonda would win an Academy Award, her first, for Klute, and would be the focus of a very different kind of nonfiction film, a cruel pendant of sorts to Jane: Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s Letter to Jane, a caustic indictment of the actress’s anti-war activism.)

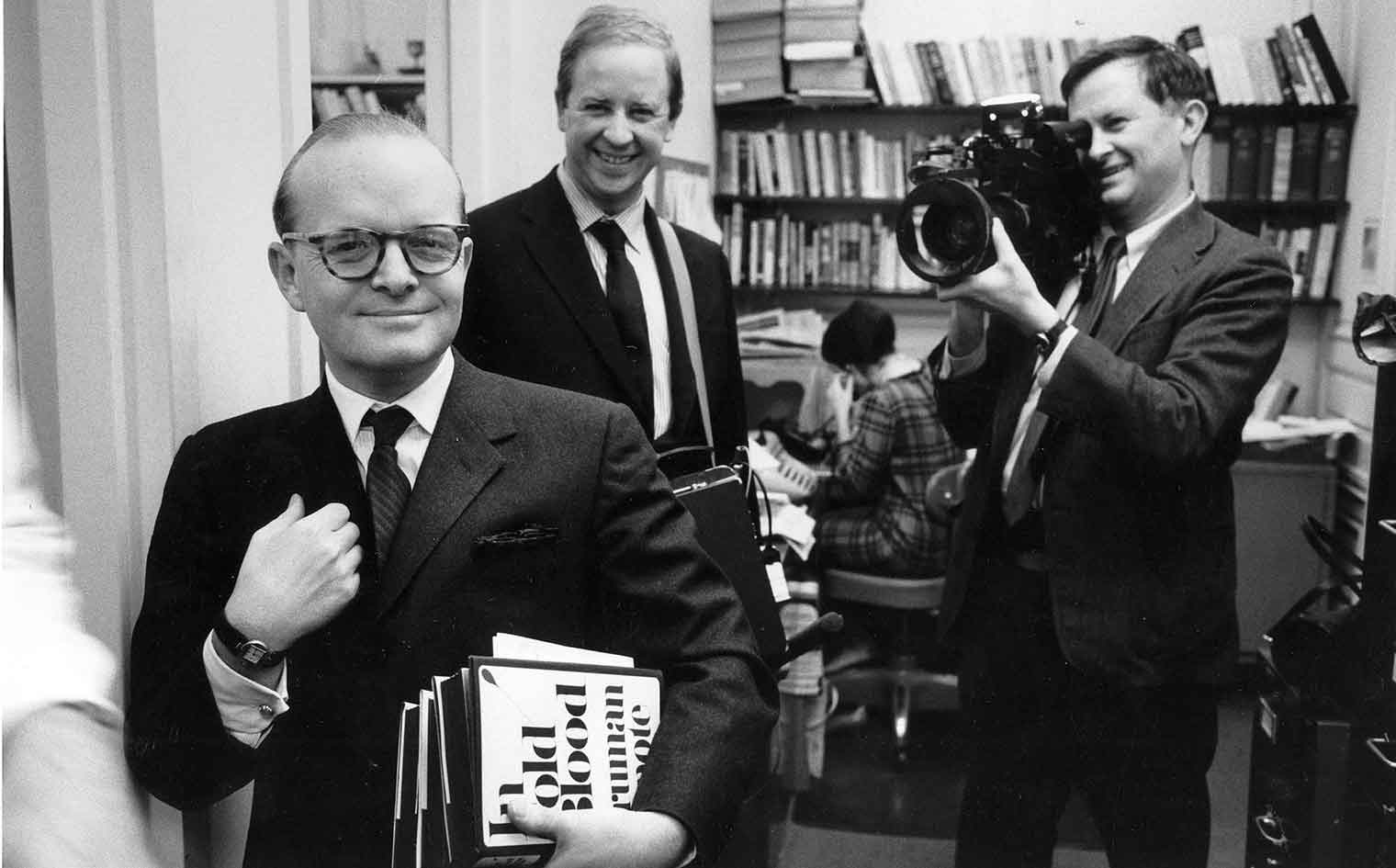

Truman Capote, David Maysles, and Albert Maysels in Albert & David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin’s A Visit with Truman Capote, 1966. Image courtesy Film Forum.

Where the central figure of Jane comes across as halting, the eponymous subject of A Visit with Truman Capote (1966) takes his genius to be self-evident. Directed by Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin, all of whom were once affiliated with Drew Associates (the Maysles brothers formed their own production company in 1962), the half-hour chronicle presents the writer just after the publication of In Cold Blood. The immense success of that “nonfiction novel”—about the 1959 murder of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas, at the hands of Richard Hickock and Perry Smith—cemented what Elizabeth Hardwick once witheringly called Capote’s “crocodilian celebrity.”

Capote is doing the publicity rounds, swooning at one man’s insistence that he’s “written a masterpiece,” fawning that the author will soon direct toward a reporter. The elfin writer greets a young woman doing a piece on him as she enters an office dominated by a teetering stack of his extoled hardcover: “Here’s Miss Karen Denison, the beautiful young interviewer from Newsweek magazine.” Soon she’s accompanying him to his house in Southampton, where Capote flaunts his Baccarat glasses, his notebooks, his photos and correspondence with Hickock and Perry, and dazzles with his explanation of his “aesthetic theory.”

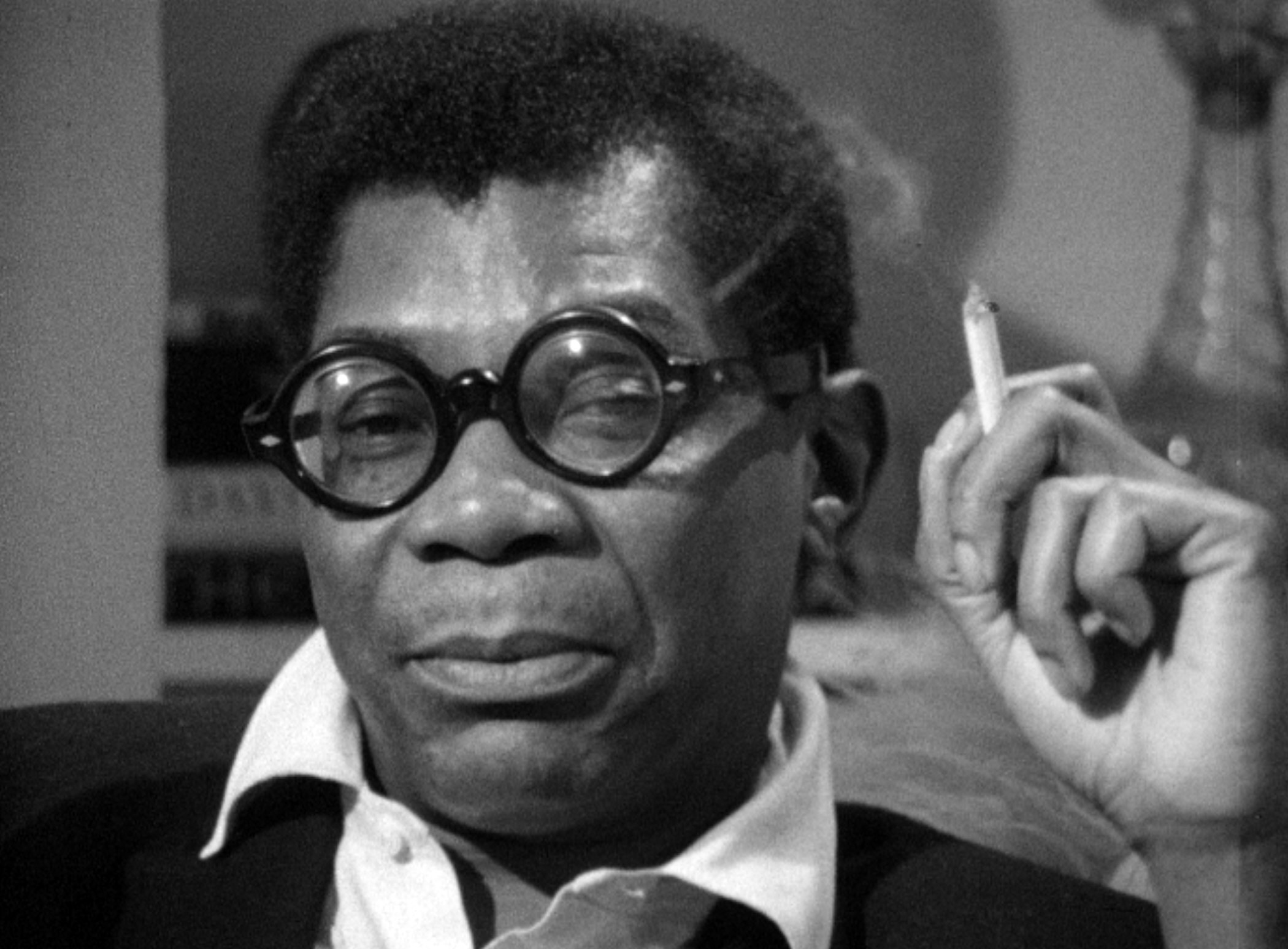

Jason Holliday in Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason, 1967. Image courtesy Film Forum via Photofest.

As with Jane, the Capote film—a fly-on-the-wall production that showcases the feted author in his Long Island kitchen as he prepares lunch for himself and Denison—gives a sense of privileged access, a window onto the “kind of truth” Drew proclaimed. But the tenets of direct cinema were soon repudiated by some of Drew’s compatriots, notably Shirley Clarke. Her Portrait of Jason (1967), a densely layered examination of a loquacious black gay hustler, underscores the fallacy of the documentarian’s claim to neutrality. In this self-reflexive work, Clarke, although not seen, is always present, growing more combative and barking orders behind the camera. Ultimately, no “truths” are revealed about the flamboyant raconteur we watch for nearly two hours; what’s disclosed instead is the theatricality of the film’s subject and of the film itself.

Portrait of Jason’s final words are Clarke’s singsong delivery of “That’s it—the end, the end. It’s over—the end, the end.” But the coda was really a beginning of an argument to be made about any nonfiction film, then or now: how much so-called verities are often shaped, compromised, and vitiated by vagaries.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns. From November 2015 until September 2017, she was the senior film critic for the Village Voice. She is a frequent contributor to Artforum and Bookforum.