Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

In a film by Richard Linklater loosely based on a true story, a philosophy professor finds his calling as a fake professional

killer for police stings.

Glen Powell as Gary Johnson in Hit Man. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Brian Roedel.

Hit Man, directed by Richard Linklater,

available on Netflix

• • •

Among the greatest pleasures of dedicated moviegoing are those moments when a performer, new to you (or so you think), knocks you out with their charisma, mien, physicality, or some combination of the three. That’s especially the case when the actor proves to be the sole source of enjoyment in an otherwise wearisome film. The only time I snapped out of my catatonia during 2022’s Top Gun: Maverick, for example, was when Glen Powell, in a supporting role as cocky naval officer Jake “Hangman” Seresin, was on the screen. Born in 1988, this handsome, gingery millennial actor impressed me with his particular style of butch confidence, a quality I associate with an earlier era, and a trait that stood out all the more whenever Powell had a scene with the now utterly unappealing, consistently overcompensating Tom Cruise. Powell called to mind the assured yet relaxed masculinity of Paul Newman and other leading men who ascended in the early 1950s to late ’60s (an era bookended by the Method and New Hollywood).

Adria Arjona as Madison Masters and Glen Powell as Gary Johnson in Hit Man. Courtesy Netflix.

But I’d seen that face a few times before, as a scan of Powell’s IMDb page later revealed: he was a member of the ensemble cast of Everybody Wants Some!! (2016), Richard Linklater’s delightful 1980-set hang-out comedy about college baseball players. The collaboration between Powell and Linklater, both from Austin, Texas, had begun a decade prior, when the actor, then in his teens, had a bit part in Fast Food Nation. In 2022, Powell voiced a NASA official in the director’s animated Apollo 10 1/2: A Space Age Childhood. Now they have teamed up for Hit Man, with Powell in the title role and with a script written by him and Linklater, their screenplay a loose adaptation of a 2001 Texas Monthly article by Skip Hollandsworth about Gary Johnson, a fake contract killer on the payroll of the district attorney’s office in Houston and a social studies instructor at a local college. A week before the press screening of Hit Man, I caught up with Anyone but You, the noxious romantic comedy starring Powell and Sydney Sweeney released late last year, in which he has all the allure of a fin-tech bro at last call. Where was that sly charmer who had so captivated me in Top Gun: Maverick? I was optimistic that he would return in the latest by Linklater, a prolific filmmaker whose Bernie (2011), also based on a Hollandsworth true-crime profile for Texas Monthly, stands among his best and gave lead Jack Black one of his greatest roles to date.

Glen Powell as Gary Johnson in Hit Man. Courtesy Netflix. Photo: Matt Lankes.

Powell’s magnetism flashes only occasionally in Hit Man—a bit ironic, considering that the movie centers on someone who, as part of his law-enforcement work, must constantly put on a performance, adopting a host of outlandish personalities to convince those who would hire him that he is a genuine assassin. Swapping Houston for New Orleans, the film opens with Powell’s Gary, a prof of psychology and philosophy who sports sexless khakis and an unflattering curtain of sideswept bangs, amiably lecturing his students about the construct of identity; these classroom scenes appear intermittently, belaboring an already obvious point about the self’s mutability. When not on campus, divorcé Gary leads a dull domestic life with cats named Id and Ego, eats cereal for dinner, and fills his leisure time with reading and birdwatching.

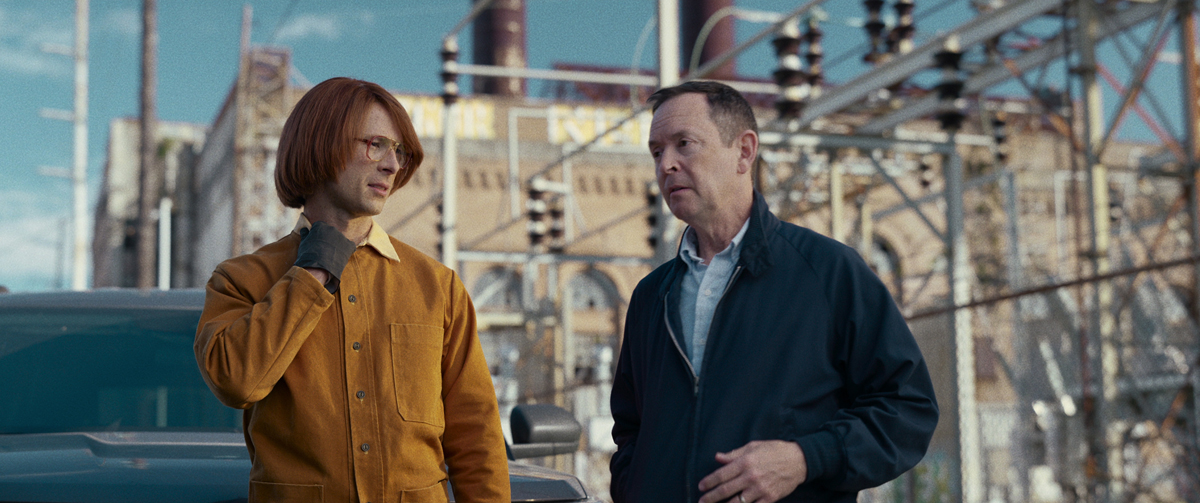

Glen Powell as Gary Johnson and Richard Robichaux as Joe in Hit Man. Courtesy Netflix.

Yet, as Gary informs us via voice-over, he also supplements his academic salary by doing surveillance work for the NOLA police department—a gig that takes an unexpected turn when he is asked to step in for the just-suspended cop who had previously served as the faux killer-for-hire in sting operations. The unassuming humanities scholar discovers he has a talent for inhabiting outsize personas. These segments rarely rise above generic buffoonery, with Powell—an actor playing a nonactor who must put on various masquerades—going bigger and broader against scene partners portraying often hackneyed versions of Deep South yokels who want to off various intimates (one exception: undercover Gary’s funny exchange with a pubescent boy who can offer only a stack of loose change and Mortal Combat games as payment to have his mom snuffed out).

Glen Powell as Gary Johnson in Hit Man. Courtesy Netflix.

The episodes become even more enervating owing to Gary’s redundant off-screen narration, once again needlessly spelling out what is already abundantly clear: “I was too shy to go out for the school play. But now I’d found my stage. And each arrest was a standing ovation.” Powell and Linklater’s storytelling strategies in Hit Man are in distinct contrast with those in Bernie, which the director wrote with Hollandsworth. In the earlier film—about a beloved mortician, Bernie Tiede, in Carthage, Texas, who kills his benefactress, Marjorie Nugent, a millionaire widow loathed by all in the hamlet—an array of characters, including several Carthage residents playing themselves, proffer opinions about this odd duo and Tiede’s trial. The polyphonic approach adds bracing specificity and unpredictability; more crucially, this Greek chorus ensures that Tiede remains a complex, contradictory protagonist. Gary’s chipper first-person voice-over, on the other hand, clangs as too beseeching, an anxious bid for the viewer’s approval.

Adria Arjona as Madison Masters and Glen Powell as Gary Johnson in Hit Man. Courtesy Netflix.

Hit Man works best when the focus is on Gary and Madison (Adria Arjona), a woman in an emotionally abusive marriage who meets with the sham murderer to discuss icing her husband. Gary, operating under the identity Ron—an alpha stud in shades and bomber jacket—immediately falls for the distressed woman and violates protocol by convincing her to leave, not kill, her spouse. She’s keen on him, too—Ron, that is, not Gary, who now must never break character as the two fall deeper in lust. Yet Madison, we later discover, is also maintaining a charade. In this noirish mode, the film’s dissembling lovers never quite suggest a twenty-first-century Walter Neff and Phyllis Dietrichson, but Powell and Arjona do generate heat together, significantly raising the temperature of this lukewarm project. My own fervor for the actor may not be as high, but Powell-as-Gary-as-Ron gave me hope that my zeal could be reignited.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.