Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

In Rosa von Praunheim’s 1971 insurrectionist cine-essay, an early—and ever-pertinent—excoriation of homonormativity.

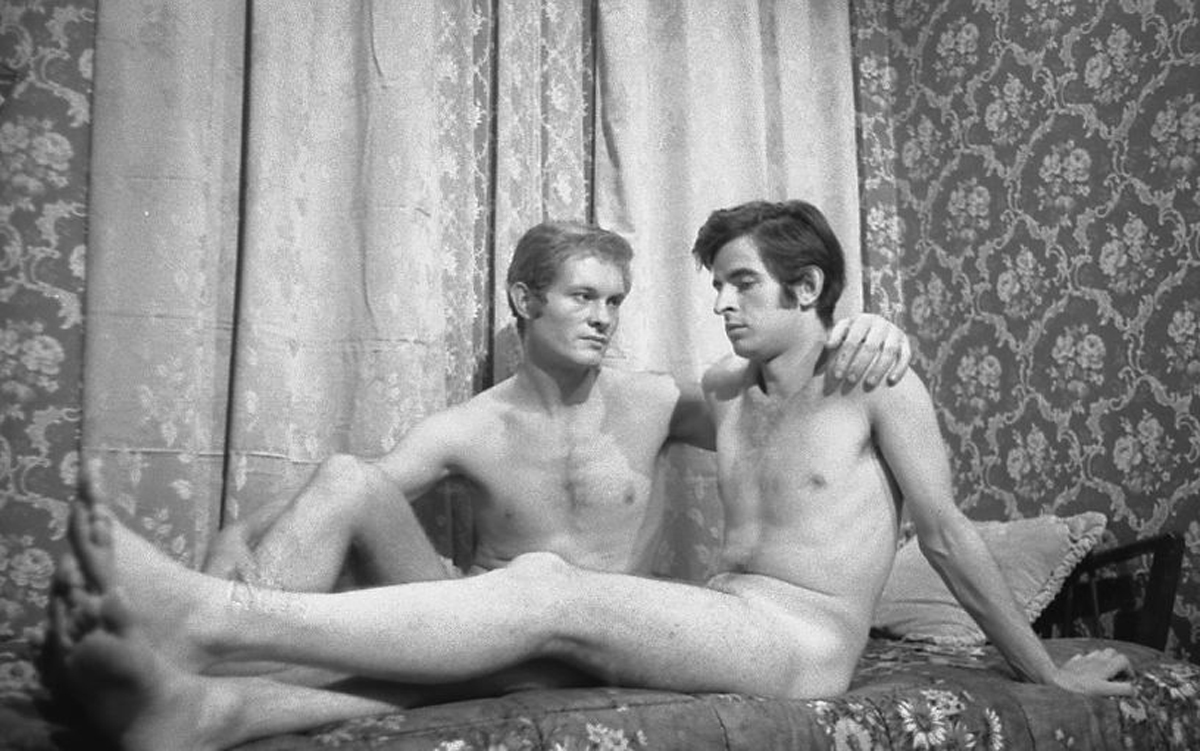

Beryt Bohlen as Clemens and Bernd Feuerhelm as Daniel in It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives. Courtesy Rosa von Praunheim Filmproduktion.

It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives, directed by Rosa von Praunheim, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, June 6 and 20, 2025

• • •

Only one word is required to summon the birth of the modern LGBTQ movement in the US: Stonewall. In what was then West Germany, however, lavender liberation commenced largely thanks to a movie with a long, tract-like title that premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in 1971—two years after the uprising on Christopher Street—and aired on German television in early 1972. A highly stylized cine-essay that suggests an inflamed Brechtian soap opera, It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives savages gay-male self-destruction and the pathological need to appease, fit into, and replicate an irredeemably corrupt and enfeebled heterosexual culture.

This was the second feature-length project by Rosa von Praunheim, born Holger Radtke in 1942. The director adopted “Rosa” both for gender ambiguity and as a reminder of the pink triangle (rosa Winkel) that gays were forced to wear in concentration camps (his bespoke surname refers to the neighborhood in Frankfurt where he grew up). Fittingly, It Is Not opens with magenta title cards before segueing to the recent arrival in Berlin of Daniel (Bernd Feuerhelm), a naïf with slicked-back hair and an ill-fitting suit. The bumpkin walks down the street with a new friend, Clemens (Beryt Bohlen), a blond butch local in a leather jacket; their getting-to-know-you small talk occurs entirely off-screen—nearly all of the sound in the film is non-diegetic, further heightening both the didacticism and the artifice of It Is Not—with von Praunheim himself providing the dialogue for each man. (The director and the film’s two narrators all speak in heavily accented English; per Vito Russo in The Celluloid Closet, the German government refused to subtitle a print, even with grant money allocated expressly for that purpose, when von Praunheim brought It Is Not to the US. These thickly Teutonic voices, at times bordering on the hysterical, add another layer of delirium.)

Beryt Bohlen as Clemens and Bernd Feuerhelm as Daniel in It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives. Courtesy Rosa von Praunheim Filmproduktion.

Next, the pair are in Clemens’s small, floridly decorated flat, the rococo interior design another element of the film’s deliberately camp sensibility, which is always in generative tension with its militant message. As they start deep-kissing, the more strident of the narrators (Volker Eschke) launches into this harangue: “Faggots don’t want to be faggots. They don’t want to be different. . . . Because they are despised by straights, who regard them as sick and inferior, faggots try to become even straighter, to compensate their guilt feelings by an overdose of bourgeois virtues. Politically apathetic, fags scramble toward conservatism out of gratitude for not being exterminated.” Decades before the term was first used, von Praunheim excoriated homonormativity.

Bernd Feuerhelm as Daniel (left) in It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives. Courtesy Rosa von Praunheim Filmproduktion.

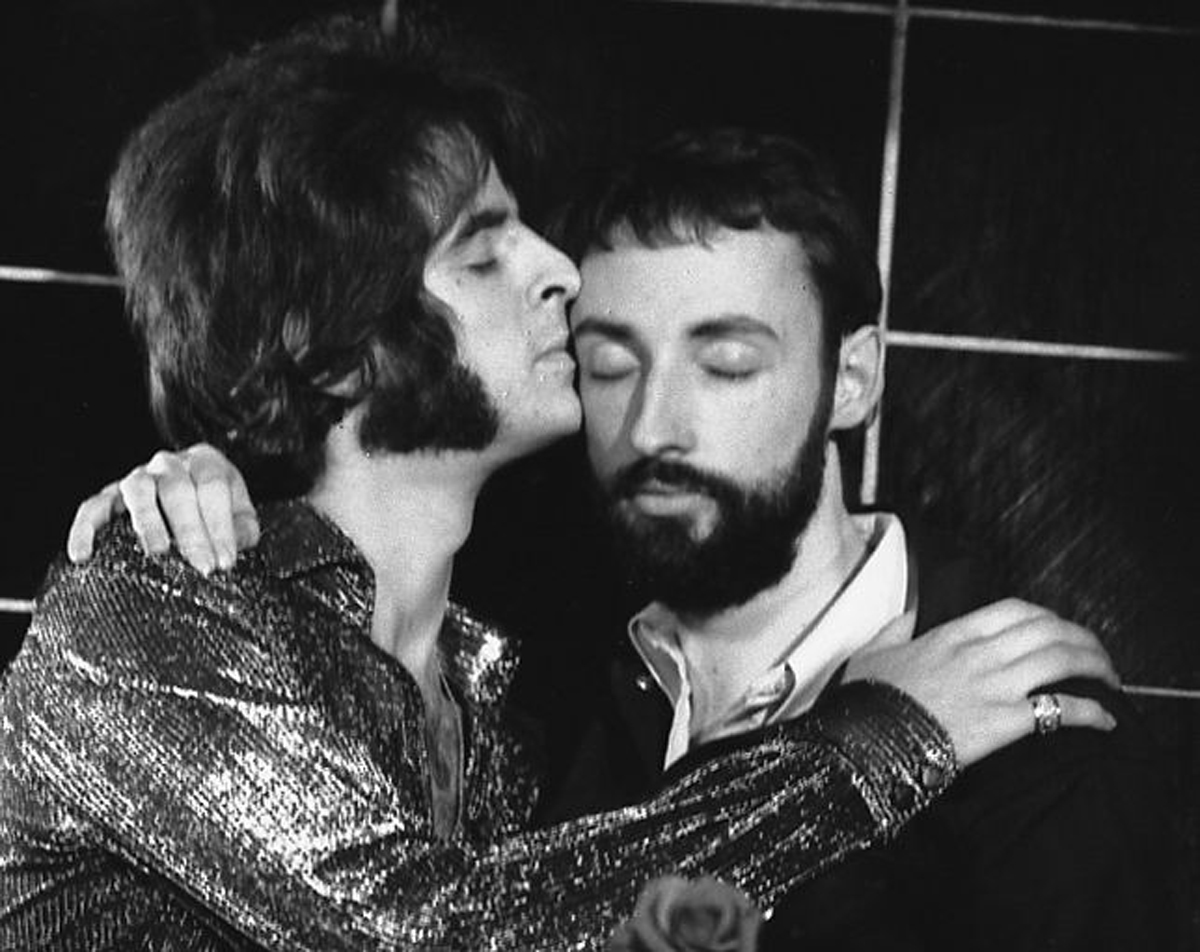

Yet It Is Not also takes pitiless aim at those practices that distinguish gay-male life from conventional straight coupledom. The film proceeds as a series of segments, rendered almost like tableaux vivants, of Daniel, now extravagantly coiffured, descending deeper into various homo identities (and attendant sartorial styles)—kept boy of a rich, middle-aged queen; bar habitué; cottager; aspiring leather daddy—while the off-screen commentary censures each of the young man’s searches for “new sexual adventures” as a dead end. For Daniel, “being a fag has become an addiction,” his pursuit of ever more exotic pleasures leaving him isolated, exhausted, and depressed.

Cast in It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives. Courtesy Rosa von Praunheim Filmproduktion.

But there is hope for the worn-out debauchee. The film’s final ten minutes showcase Daniel in a kind of consciousness-raising session with five members of a radical gay commune. At this naked be-in, the quintet exhorts the weary homosexual to leave the gay ghetto behind. Self-hatred, infighting, and the meaningless fuck must go to make way for a gay pride that is essential to coalition-building and overthrowing stifling heteropatriarchal mores. “We’ve got to become erotically free and socially involved. Let’s work together with the Blacks and with women’s liberation against the oppression of minorities. Get involved politically. Being gay isn’t a career,” urge the communards.

Bernd Feuerhelm as Daniel (foreground) and cast in It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives. Courtesy Rosa von Praunheim Filmproduktion.

Von Praunheim’s film inspired some of his compatriots to take up his call to arms: the gay-rights organization Homosexual Action West Berlin was formed largely in response to It Is Not. But when the German firebrand first screened his movie for New York audiences in 1972, several attendees wanted to call for his head. MoMA’s presentation of It Is Not (screening as part of the series “Queer and Uncensored,” running through June 27) also includes roughly thirty minutes of Q&A footage between von Praunheim (accompanied by Eschke) and Gothamites heatedly responding to the film, first at MoMA and then at the Gay Activists Alliance headquarters in SoHo. “You depicted the absolute worst aspects of gay life,” one spectator snarls. “You dislike yourself, apparently,” sneers another. Von Praunheim and Eschke patiently absorb the invective, while standing firm in their belief that “the gay life is not healthy at all” and that the purpose of It Is Not is “to make gay people more political.”

Bernd Feuerhelm as Daniel (left) in It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives. Courtesy Rosa von Praunheim Filmproduktion.

Despite this hostile reception, von Praunheim did not sour on the US—quite the contrary. A few years later he would tour the country, trying to take the pulse of the still relatively young gay-lib movement, a coast-to-coast chronicle that he assembled as Army of Lovers or Revolt of the Perverts (1979). He’s made several films in and about NYC, including one of my favorite documentaries, Tally Brown, New York (1979), a mesmerizing portrait of not only the cult performer of the title but also of the Manhattan homo redoubts, long since shuttered, where she sang, like the cabaret-revival club Reno Sweeney.

Wildly prolific, von Praunheim, now eighty-two, is still making films. None has quite the deranging intensity of It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, but the Society in Which He Lives; simply saying the title in full feels like uttering an incantation. More than a half century later, this insurrectionist work, while a relic in many regards, continues to spotlight issues far from resolved. Those tetchy rejoinders from New York audiences in ’72 are an early example of the ongoing, increasingly reductive discussion regarding “positive” queer images. And the film’s declaration that “being gay isn’t a career” remains timely, with one amendment: swap out “career” for “brand.”

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press. A collection of her film criticism, The Hunger, will be published this year by Film Desk Books.