Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Ira Sachs’s hypnotic portrayal of a daylong conversation between the photographer and his longtime friend Linda Rosenkrantz.

Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz and Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar in Peter Hujar’s Day. Courtesy Janus Films.

Peter Hujar’s Day, written and directed by Ira Sachs,

now playing in theaters

• • •

The setup for Peter Hujar’s Day could not be sparser: two people in an apartment talk for several hours. Yet within this skeletal framework blooms an abundance of memories, emotions, affection, and aspirations. Nothing less than a friendship, a life, an era are beautifully evoked and distilled.

Ira Sachs’s film adapts a slender 2021 book of the same name, itself a transcript of a conversation that took place on December 19, 1974, between the writer Linda Rosenkrantz and her friend of nearly twenty years, the photographer Peter Hujar, at her East Ninety-Fourth Street digs. While he was little-known at the time, Hujar’s portrait of Candy Darling, in full maquillage and cocooned in her hospital-bed duvet, had appeared in the New York Post earlier that year in a feature announcing the Warhol Superstar’s demise. (Candy Darling on Her Deathbed now ranks among the most canonical of Hujar’s photographs of downtown savants, many queer and/or trans, who also include experimental-theater mage Ethyl Eichelberger and artist Greer Lankton, creator of sinisterly glam life-size dolls.)

Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz in Peter Hujar’s Day. Courtesy Janus Films.

Their chat was occasioned by Rosenkrantz’s earlier proposal to her pal that he write down everything he did on a randomly chosen day—December 18—and recapitulate those activities at her place the next morning while a tape recorder rolled. Rosenkrantz had already proven herself a maestra of that device, indispensable for her 1968 book Talk, an edited transcript of dishy discussions from the summer of 1965 among the author and two likewise artistically ambitious friends: another straight woman and a gay man (given a pseudonym in the book—as were his two interlocutors—he is the painter Joseph Raffael, a previous boyfriend of Hujar’s who had introduced Rosenkrantz to the photographer in 1956).

While Talk is a colloquy rich in vitamin G, aka gossip, Peter Hujar’s Day is, by design, mostly a monologue (though one also enhanced by that essential nutrient), with Rosenkrantz occasionally asking clarifying questions or adding her own commentary. Among the many delights of Sachs’s movie is witnessing the dramatization of this exchange, in which the intimacy of a two-decade friendship is conveyed not only through his detail-dense yet relaxed recounting and her attentive listening but also by looks, gestures, and touch.

Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz and Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar in Peter Hujar’s Day. Courtesy Janus Films.

Rosenkrantz and Hujar were both born in 1934, she in the Bronx and he in New Jersey, though he moved to Manhattan as an eleven-year-old and would die there, in 1987 at age fifty-three, of AIDS-related causes. (Rosenkrantz, now ninety-one, is still very much with us.) These two inveterate New Yorkers are played by two Brits, Rebecca Hall and Ben Whishaw. The casting of the latter initially filled me with incredulity: How could the wispy 5′9″ performer, who first worked with Sachs in 2023’s Passages, a febrile drama about the implosion of a love triangle, convincingly portray the darkly brooding, strapping 6′3″ photographer?

Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz and Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar in Peter Hujar’s Day. Courtesy Janus Films.

Yet my doubts were extinguished as soon as the actor began speaking. I have no idea what Hujar sounded like, but Whishaw’s astute delivery of reams of dialogue makes questions of resemblance—physical or verbal—ultimately irrelevant. (Hall, for her part, does a credible outer-borough accent.) As Peter chronicles his doings from the day before, his recollection takes on an incantatory power, a hypnotic effect heightened by Whishaw’s expertly timed pauses, his changes in posture or bodily position. This choreography of speech is mirrored by Peter and Linda’s movements around the apartment, a pas de deux of sorts that finds them sitting across from each other in her living room, standing side by side on the roof of her building, or lying together on her bed, his head sometimes in her lap.

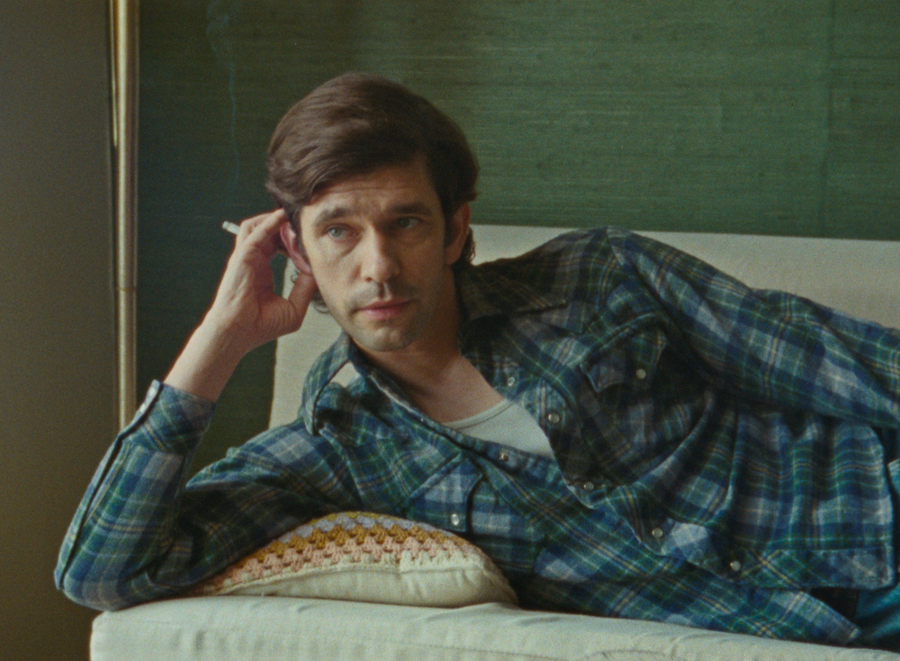

Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar in Peter Hujar’s Day. Courtesy Janus Films.

Supine, Peter evokes the pose of several of his subjects (including himself) in Portraits of Life and Death (1976), the only book he published in his lifetime. Among those on their back in that collection is Susan Sontag, who here is one of a constellation of luminaries that, on the day being recounted, Hujar spoke to on the phone (Fran Lebowitz also rang him up), photographed (Allen Ginsberg proves very tetchy when Hujar arrives at the Beat bodhisattva’s tenement to take his picture for a New York Times assignment), or otherwise interacted with (the music and photography critic Vince Aletti, a confidant and neighbor, comes over to Hujar’s East Village loft to take a shower). Just as riveting as the tales involving those personages are the mundane aspects of Peter’s December 18, 1974: the liverwurst sandwiches he had for lunch, the erratic heat in his apartment, his observations while waiting for Chinese takeout, the price of a pack of cigarettes, his late-night hours at his at-home darkroom, the tallying of money still outstanding for commercial work, concerns about worsening eyesight and aging in general (Peter and Linda were both forty on this date). His quotidian inventory is a catalogue raisonné.

Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar and Rebecca Hall as Linda Rosenkrantz in Peter Hujar’s Day. Courtesy Janus Films.

While Sachs’s film is exceedingly faithful to the source text, there are a few deviations. A geographical switch felicitously reflects a milieu favored by the photographer. Peter Hujar’s Day was shot not in an Upper East Side flat, where the actual conversation took place, but in an apartment at the Westbeth, the artists’ housing complex founded in 1970 in the far West Village, a neighborhood often shot by Hujar: he captured its abandoned lots in the dead of night and guys cruising at the piers in broad daylight. When Peter and Linda go on the roof to continue their talk, the Hudson River, another of Hujar’s frequent subjects, flows behind them. But other interventions, namely Sachs’s insistence on breaking the fourth wall several times throughout the film—we see and hear scenes being slated; Hall looks directly at the camera while Mozart’s “Requiem in D Minor” blasts—do nothing but unnecessarily distract and disrupt, removing us from our full immersion into this specific time, location, and person.

Ben Whishaw as Peter Hujar in Peter Hujar’s Day. Courtesy Janus Films.

Fortunately, we slip back easily into this bygone world, for it’s not only Peter’s words that entrance. Shot on 16mm, Sachs’s film focuses on the humble yet potent drama of a darkening room, a crepuscular sky, the way shadows fall across the faces of Peter and Linda. Near the end of their conversation, Peter tells his friend, “I realized to do good work, I really need time to look at it, really see what I’m doing. Sometimes I just stand there and stare at it and it’s even rather pleasurable.” Peter Hujar’s Day reminds us of the pleasures of looking and listening intently.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press. A collection of her film criticism, The Hunger, will be published this month by Film Desk Books.