Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

On a road to nowhere? A new restoration of Jonathan Demme’s 1984 Talking Heads documentary.

Lynn Mabry and David Byrne in Stop Making Sense. Courtesy A24. Photo: Jordan Cronenweth.

Stop Making Sense, directed by Jonathan Demme, now playing in theaters

• • •

As Heraclitus himself surely knew, no woman experiences the same concert documentary twice. A fixture of my youth, Stop Making Sense, Jonathan Demme’s heralded 1984 film capturing Talking Heads live on stage, has been rereleased in a new 4K restoration. Having thrilled to a half-dozen viewings in my adolescence and early twenties, I returned to it for the first time in at least thirty years earlier this month. A movie that I once watched with unadulterated delight has now been vitiated somewhat by my evolving antipathy toward the group’s front man—an art-pop despot who has since remade himself as a mezzo-maestro of the most anodyne projects promoting “community.”

Stop Making Sense was shot over three nights in December 1983 at Hollywood’s Pantages Theatre. That venue was the terminus of the band’s tour of the same name, taking its title from a lyric in “Girlfriend Is Better,” from Speaking in Tongues, their fifth album and commercial-breakthrough LP. By the time of the tour, Talking Heads—composed of Rhode Island School of Design confederates David Byrne (guitar and lead vocals), Chris Frantz (drums), and Tina Weymouth (bass), plus Jerry Harrison (guitar and keyboards), the last to join—had been together for roughly six years. Their albums—New Wave infused with avant-disco and global funk—were critically lauded; their aims, solemn. As Weymouth, who married Frantz in 1977, told Dick Clark in ’79 when the group was on American Bandstand, “We wanna make our mark in music history.”

Still from Stop Making Sense. Courtesy A24. Photo: Jordan Cronenweth.

That seriousness of intent was enhanced by Byrne’s stage persona. Wild-eyed and twitchy, he seemed to be describing himself when he sang, from “Psycho Killer,” a track on their debut album, “I’m tense and nervous and I can’t relax.” The front man’s spidery tenor displayed reticence and release in equal measure. As Frantz writes of his bandmate in his 2020 memoir, Remain in Love, “He sang with real feeling and in his weird vocal style you could hear the pain of creation.”

Jerry Harrison and Chris Frantz in Stop Making Sense. Courtesy A24. Photo: Jordan Cronenweth.

With creation came rising tensions in the band, largely owing to Byrne’s increasingly autocratic rule—he himself has recently admitted that he was “more of a little tyrant” back then—and, as at least one other Talking Head has insisted, his claiming of sole authorship of songs, such as “Life During Wartime,” that were joint collaborations (Frantz: “This happened to us all the time with David. He couldn’t acknowledge where he stopped and other people began”). Accounts of discord in a rock band, particularly as it was growing in popularity, are to be expected, especially when they are written decades after a group’s demise (Frantz’s book was published almost thirty years after Talking Heads broke up in 1991). But with this knowledge, my experience of Stop Making Sense changed. In my inaugural viewings, I focused on the group’s cohesion. Now I could see only its atomization, its extremely talented members forced to orbit its proprietary lead singer.

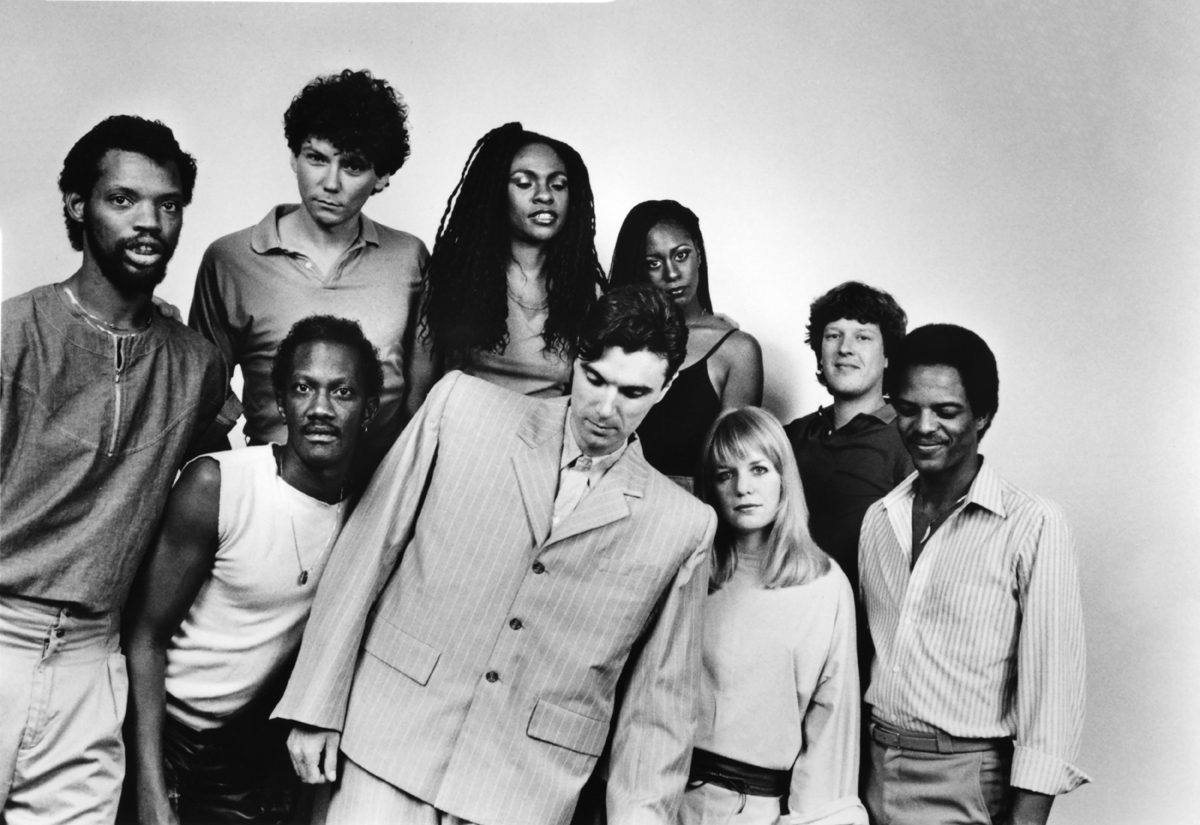

Jerry Harrison, Ednah Holt, Lynn Mabry, and Chris Frantz (left to right, back row); and Steve Scales, Bernie Worrell, David Byrne, Tina Weymouth, and Alex Weir (left to right, front row) in Stop Making Sense. Courtesy Sire / Warner Music Group.

Greatly inspired by Robert Wilson’s stark theatrical tableaux, Byrne oversaw the plotting of the “Stop Making Sense” tour, the first of Talking Heads’ live shows to involve stage production. Byrne, unsurprisingly, is the first to appear: the documentary begins with a close-up of his white canvas sneakers striding to the microphone, the camera then panning up to reveal the singer in a loose-fitting pewter-gray suit. “Hi. I got a tape I wanna play,” he impassively greets the audience, activating a boom box that emits a drum-machine track to accompany his acoustic guitar for a solo performance of “Psycho Killer.” With crew members moving more equipment on stage, Weymouth comes out next, her bass prominently featured on “Heaven.” That song complete, Frantz joins for the infectiously propulsive “Thank You for Sending Me an Angel”; Harrison arrives for “Found a Job.” After the core quartet is gathered, three additional musicians—Bernie Worrell, Steve Scales, and Alex Weir, all of whom were part of the Speaking in Tongues personnel—plus the backing vocalists Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt complete the ensemble.

Ednah Holt, Jerry Harrison, and Lynn Mabry in Stop Making Sense. Courtesy A24. Photo: Jordan Cronenweth.

Writing recently about the restored documentary, Jon Pareles noted in the New York Times, “If there’s a narrative to Stop Making Sense, it’s of a freaked-out loner who eventually finds joy in community,” reiterating what has long been an article of faith about the movie. The exuberance and energy of the band in Demme’s film are undeniable. But during Byrne’s highly calisthenic performance—his serpentine shimmy and sprint around the set accentuating “Life During Wartime,” for example—he seems willfully isolated, set apart from his collaborators. He evinces more affection and camaraderie for the floor lamp that doubles as his dance partner during the love song “This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)” than he does for any of his bandmates.

Tina Weymouth, Ednah Holt, Lynn Mabry, David Byrne, and Alex Weir in Stop Making Sense. Courtesy A24. Photo: Jordan Cronenweth.

While Byrne remains outwardly focused throughout that number, Weymouth, in contrast, smiles beatifically as she looks admiringly at Mabry and Holt, then Weir, then the lead singer. Shortly after “This Must Be the Place,” Byrne exits the stage, ceding the show for one song to the Tom Tom Club, the side project Weymouth and Frantz started in 1981. As a jubilant Frantz exhorts “Check it out!” the band tears into “Genius of Love,” the TTC’s monster club hit. Weymouth, on lead vocals, falls into an easy rhythm with Mabry and Holt and with Weir; they seem to be her equals, not her adjutants.

Byrne’s fleeting pause from the show was less an act of generosity than a necessary interval for a costume change: he returns to the set in the legendary, ostensibly Noh-inspired “big suit,” a dove-gray Brobdingnagian jacket and trousers. Byrne still likes suits and that muted hue, but shoes he can apparently dispense with: his 2019 Broadway show, American Utopia, featured him and a score of other performers in matching gray suits, all unshod. That’s just one of several Byrne projects from the past decade that have endeavored to exalt the power and beauty of the collective, peddling the toothless politics of optimism and good vibes in wretched times. Another is Reasons to Be Cheerful, a nonprofit online magazine he founded that “aims to inspire us all to be curious about how the world can be better, and to ask ourselves how we can be part of that change.” Stop making nonsense.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.