Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

A strikingly incompatible Marianne Faithfull and Alain Delon star in Jack Cardiff’s fascinating and bizarre biker film from 1968.

Marianne Faithfull as Rebecca in The Girl on a Motorcycle. Courtesy Film Forum.

The Girl on a Motorcycle, directed by Jack Cardiff, screening April 16, 2024, Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City

• • •

Ten years after the release of The Wild One (1953), starring Marlon Brando as Johnny, leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club, the biker film entered its glory years. For the next decade or so, the genre—primarily Anglophone, with most titles made in the US—would be a staple of the exploitation circuit. But the motorized two-wheeler wasn’t limited to just the B-picture. It is the central fetish object in Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963), a paragon of queer avant-garde cinema. And in 1969, the biker movie achieved worldwide respectability with Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, which was anointed the best first film at Cannes that year and became a foundational work in the New Hollywood canon.

Released in 1968, Jack Cardiff’s The Girl on a Motorcycle stands as one of the strangest outliers in the chopper corpus. Shot mainly in France, Germany, and Switzerland, it boasts serious Europhilic bona fides: the British Cardiff—who came to prominence as the cinematographer for Powell and Pressburger’s most exalted postwar Technicolor marvels, such as The Red Shoes (1948)—based the movie on La Motocyclette (1963), by the French novelist André Pieyre de Mandiargues, an eventual Prix Goncourt winner. The film’s male lead is played by Alain Delon, then the reigning Gallic male sex symbol. As the title announces, another distinguishing trait of Cardiff’s movie is the gender of the rider. The “girl” is Rebecca, portrayed by Marianne Faithfull, the UK’s premier folk-rock chanteuse at the time and a key figure in the Swinging London scene thanks to her highly public romance with Mick Jagger, her lover from 1966 until 1970.

Marianne Faithfull as Rebecca in The Girl on a Motorcycle. Courtesy Film Forum.

The title given to The Girl on a Motorcycle when it was later reissued—Naked Under Leather—hints at yet another of its distinctions: it was the first film in the US to receive an X under the ludicrous, just-introduced rating system (Warner Bros. made edits to secure an R). In her 1994 autobiography, Faithfull calls the movie “soft porn,” which, considering how frenziedly unerotic it is, doesn’t quite ring true. Her other descriptor of Cardiff’s project—“terrible”—hits closer to the mark.

But even bad movies are not without their fascinations and oddities; watching The Girl on a Motorcycle proves to be an equally bracing and wearying experience. It starts spectacularly: the credits zoom at us as the camera, assuming the POV of a motorcycle’s engine, speeds down a two-lane highway. (Cardiff also served as the director of photography.) Next, we are plunged into one of Rebecca’s dreams, a psychedelic vision of humiliation rituals set at a circus segueing to a solarized sequence, in lysergic hues of green, lilac, and orange, of Rebecca atop a wild horse on a beach.

Marianne Faithfull as Rebecca in The Girl on a Motorcycle. Courtesy Film Forum.

While the eye is often ravished in The Girl on a Motorcycle, the ear is frequently assaulted, the result of the relentless use of voice-over to articulate Rebecca’s interior monologue, which begins as soon as she wakes up from her REM sleep. “Skin. It’s like skin. I’m like an animal,” she coos, caressing the fleece-lined catsuit that she will soon step into (truth in advertising: she wears the garment with no underclothes). Walking out into the dawn fog, Rebecca opens the garage to engage in even more paraphilic attachment, sighing “Ah, there he is” to her Harley-Davidson Electra Glide, fondling it lasciviously. Then she’s off, zipping down the roads of Haguenau—the town in Alsace where she lives with her fatally kind, too-acquiescent cello-playing schoolteacher husband, Raymond (Roger Mutton), still asleep in their bed. Her destination: Heidelberg, where she will be reunited with her caddish paramour, Daniel (Delon), a philosophy professor who lectures his students on free love.

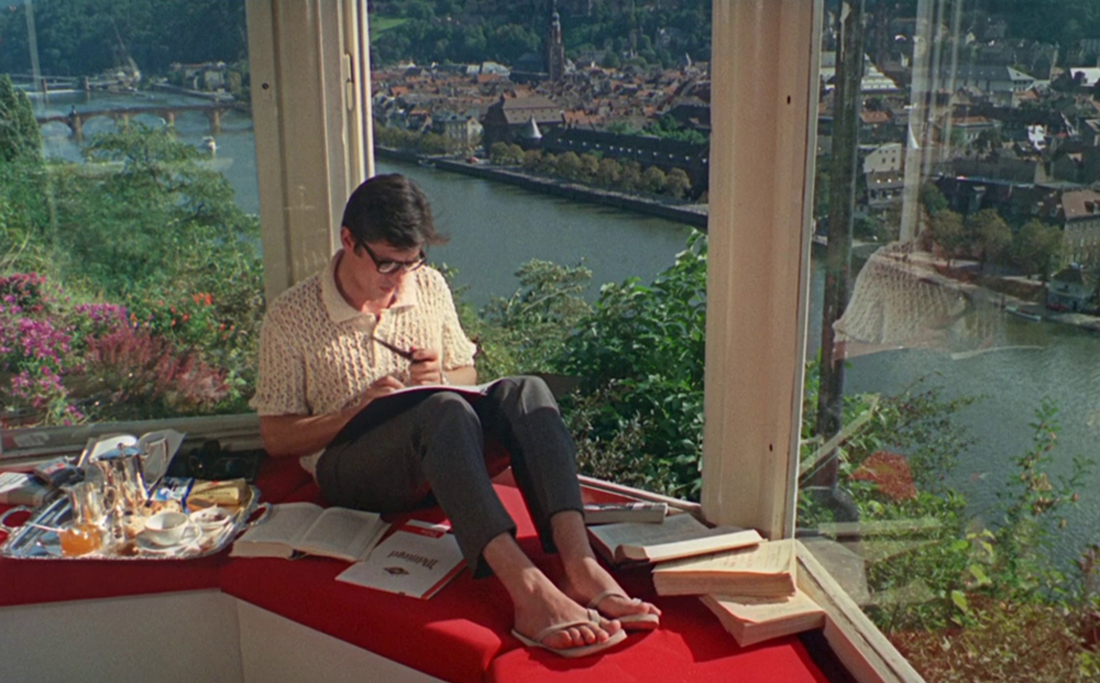

Alain Delon as Daniel in The Girl on a Motorcycle. Courtesy Film Forum.

During this roughly seventy-five-mile trip, one Rebecca has made many times before, she will have innumerable reveries that cue flashbacks recounting how she met Daniel, how she got that motorbike, how she likes to be treated by men. At the time of that fateful first encounter with the roué, at her father’s bookshop in Geneva, Rebecca is a proper jeune fille, partial to hair bows, modest skirts, and couples’ ski holidays with Raymond. Nothing turns her on quite like the philosophy prof’s negging.

Alain Delon as Daniel in The Girl on a Motorcycle. Courtesy Film Forum.

Or so we are forced to believe. Like two protons, Delon and Faithfull repel each other, their utter lack of onscreen chemistry constituting a colossally failed science experiment. “He was such a pompous ass,” Faithfull recalls of her costar in her memoir. “Every time he said that ludicrous line ‘Your body is like a beautiful violin in a velvet case,’ while unzipping my leather suit, I would crack up. It was dozens of takes before I could do it with a straight face.” There is no mention in her book of how many times she had to deliver this come-on to her Electra Glide before Cardiff deemed the results satisfactory: “My black devil! You make love beautifully, like my red devil, Daniel. . . . Take me to him, my black pimp!” (This apostrophe typifies the moments in the film when the director “becomes a sort of D. H. Lawrence of the Harley-Davidson,” in the words of the redoubtable Renata Adler, in her review for the New York Times.)

Marianne Faithfull as Rebecca and Alain Delon as Daniel in The Girl on a Motorcycle. Courtesy Film Forum.

By the following year, though, both leads would find projects with far more compatible partners. In Jacques Deray’s La Piscine, a steamy tale of high-stakes hedonism set in the Côte d’Azur, Delon and Romy Schneider play the central couple of a debauched foursome. Lovers in real life from 1958 to 1963, these two obscenely beautiful performers remained close after they broke up; Delon, in fact, demanded that his ex be cast opposite him. Tony Richardson, impressed by Faithfull’s work onstage as Irina in Three Sisters, cast her as Ophelia in his production of Hamlet, which opened at London’s Roundhouse theater in March ’69 and would be adapted for film a few months later. She and Nicol Williamson, who played the prince of Denmark, were having an affair; Faithfull says of the actor, “Nicol was very mad and possessed and helped me a lot, especially with the technical stuff, the Shakespearean meter.” After the joyless experience of uttering Rebecca’s fatuous inner ramblings, Faithfull must have been ecstatic to speak in the Bard’s iambic pentameter.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.