Ratik Asokan

Ratik Asokan

In Mário de Andrade’s 1928 novel, a modernist spin to the shape-shifting trickster from Brazilian folklore.

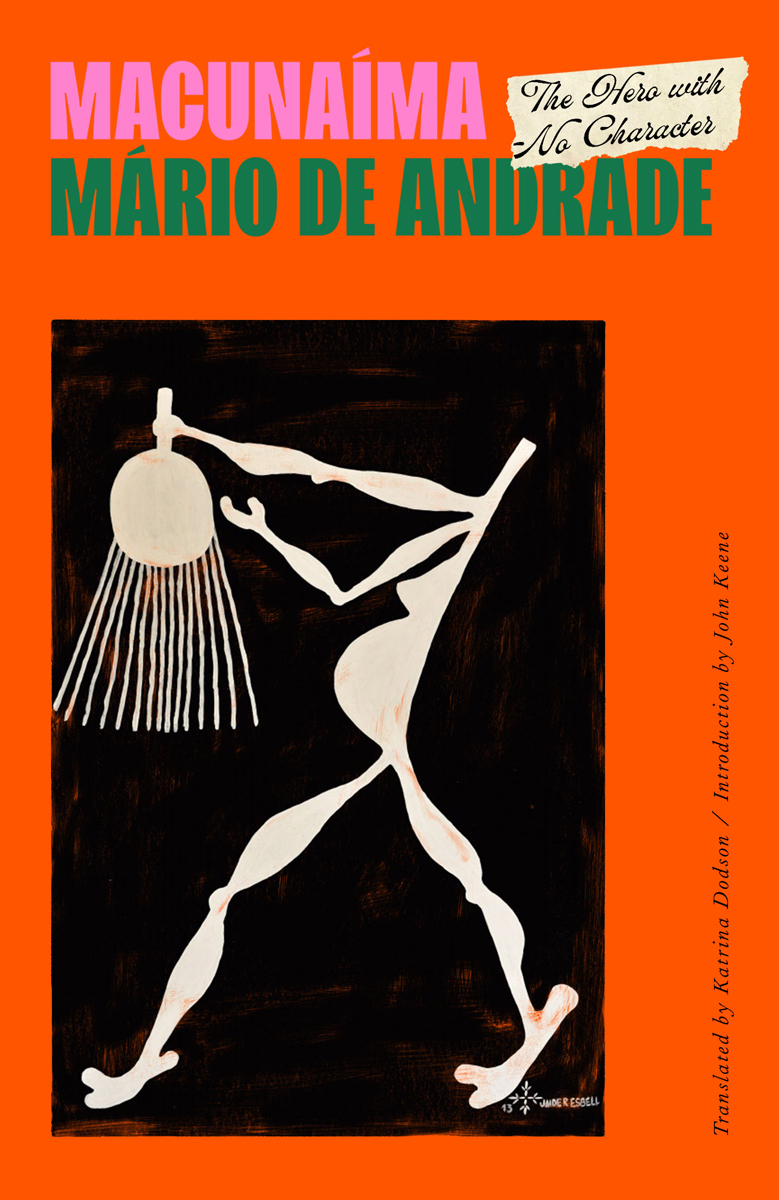

Macunaíma: The Hero with No Character, by Mário de Andrade, translated by Katrina Dodson, New Directions, 264 pages, $17.95

• • •

A charming late essay by Hans Magnus Enzensberger is titled “How to Invent Nations at Your Desk.” In it, he revisits the mania for philology that swept across Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, when scholars on the margins of empire—in Norway and Finland, Estonia and Serbia—hunkered down in libraries with the curious agenda of digging up local tradition. “All longed to become a real nation, sovereign and independent,” Enzensberger writes. But that required a “proper national culture,” which their people sadly lacked. And so they set about “collecting their old songs, folk tales and sagas, composing dictionaries and grammars,” which anti-imperial movements later drew on. Many were duly anointed “father of the fatherland” at independence.

One way to read Mário de Andrade’s Macunaíma is as a parody of such nationalist texts. This cult 1928 novel, newly translated by Katrina Dodson, grew out of what its author describes as “my constant preoccupation with delving into and learning as much as I can about the national entity of the Brazilian people.” It was a preoccupation shared by many elites of his generation, the first to come of age after slavery and the monarchy were abolished; they were plagued by the sense that Brazilian culture was merely imitative of Europe. As Andrade puts it in the preface: “The Brazilian has no character because he possesses neither his own civilization nor a traditional consciousness.” In response, one school of intellectuals, led by sociologist Gilberto Freyre, looked for an original identity in the mystical union of Brazil’s three major races: white, Black, and Indigenous. Mixed-race himself, Andrade offered a more provocative if less serious answer.

Like his European forebearers, Andrade sought Brazil’s “proper national culture” not among the masses but in the library. In 1926, he came across the second volume of From Roraima to the Orinoco (1924), German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg’s five-part study of Carib and Arawak peoples. An avid folklorist, who set up Brazil’s first Society for Ethnography, Andrade was enchanted by the tribal myths the scholar recorded. He was especially drawn to those of Tuarepang and Arekuna peoples—part of the Carib group known as Pemon, who live in the Amazon rainforest—and in specific to a story cycle about a shape-shifting trickster named Makunaíma. Ironically deciding that this figure embodied “the best elements of a national culture,” Andrade sat down to write a modern update of the story cycle. The task was largely completed in six feverish days.

To describe Macunaíma as sui generis would hardly scratch the surface. In Andrade’s view, it is less a novel than “an anthology of Brazilian folklore,” which is true in that he borrowed heavily from Koch-Grünberg. “It is the Pemon Makunaíma who gives Mário de Andrade’s protagonist his most important qualities,” Lúcia Sá notes in Rain Forest Literatures: Amazonian Texts and Latin American Culture. “His name, his ability to transform into other beings, a good portion of his malice and mischief, his capacity for boredom, and his status as a hero.” Secondary figures—Macunaíma’s older brothers, “Maanape the geezer and Jiguê in the prime of manhood”; his nemesis, “Piaimã the Giant, eater of men”—are also drawn from the ethnographic text. As are key plot elements, like the opening scene in which Macunaíma transforms into an adult to sleep with Jiguê’s wife. This is from Koch-Grünberg: “Makunaíma was still a boy. But when they arrived there, he turned into a man and forced her.” And this is from Andrade: “No sooner did the boy touch the leafy forest floor than he turned into an ardent prince. They played around.”

Yet Macunaíma is anything but a simple retelling. Andrade is fast and loose with the source material, mixing anecdotes from other traditions, adding historical figures, and leading his hero across landscapes both ancient and modern. The style that emerges is a kind of folk surrealism: marked by cartoonish violence, bawdy humor, and, above all, constant motion.

Macunaíma unfolds in a series of picaresque episodes. “In the depths of the virgin-forest was born Macunaíma, hero of our people,” runs the first line. “He was jet black and son to fear of the night.” From there, the adventures rush forth, as the brothers journey through the Amazon, fighting monsters (“Right then a colossal roar was heard and Capei came surging out the water. And Capei was the boiuna snake”) and courting goddesses (“It was Ci, Mother of the Forest. . . . The woman was beautiful, her body ravaged by vice and painted with jenipapo”). When Macunaíma loses his magical amulet, the muiraquitã, they go to São Paulo to retrieve it from the capitalist Venceslau Pietro Pietra, a reincarnation of Piaimã. Andrade depicts the city through primitivist eyes: “The pumas weren’t pumas, they were called Fords Hupmobiles Chevrolets Dodges Marmons and they were machines.” The quest completed, they return home, where Macunaíma later dies of boredom. “I’ve sung these cares to the world, telling all the sayings and doings of Macunaíma, hero of our people,” Andrade concludes. “And that’s all.”

In this aimless, amoral tale, a few scenes stand out for their winking political symbolism. Early on, Macunaíma bathes in an enchanted whirlpool, which turns him entirely white. Amazed and jealous, his brothers jump in, only to find the water has been dirtied, leaving their transformations incomplete: “And it was the loveliest sight under the Sun on that rock the three brothers one blond one red another black, standing up tall and naked.” Later, our hero agrees to marry a daughter of the sun Goddess, Vei, but then cheats on her with a white woman. As punishment, Vei places an illusion of a “rosy-cheeked” nymph on an island in a cursed river, tricking him into jumping in. That is how he loses his muiraquitã for good, as well as his will to live. These scenes gently send up the aspirational whiteness or European-ness that Andrade felt had deformed Brazilian society. He addresses the matter in his preface: “[I] have been preoccupied with the issue of our having formed, or wanting to form, a culture and civilization based on a Christian-European foundation.”

Macunaíma is chock-full of such elaborate allegories, which have kept interpreters busy. (This edition has forty-one pages of endnotes.) Nonspecialist readers, however, are likely to find many of the book’s hijinks simply confusing. A more serious issue is that the narrative lacks imaginative depth, in contrast, say, to Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home (1985) or Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Storyteller (1987)—which also engage Indigenous folklore from a non-Native perspective. Perhaps, then, the novel’s value is best defined negatively. By presenting, as the symbolic Brazilian, a race-swapping Indigenous trickster, Andrade upends the older myths of Brazil as a European outpost or color-blind democracy. His was a creative exercise in laying bare the false ideologies on which his country’s self-image was based. In that sense, every nation needs its own Macunaíma.

Ratik Asokan is a writer. He lives in New York.