Eric Banks

Eric Banks

A smoker looks back at the pleasures of addiction.

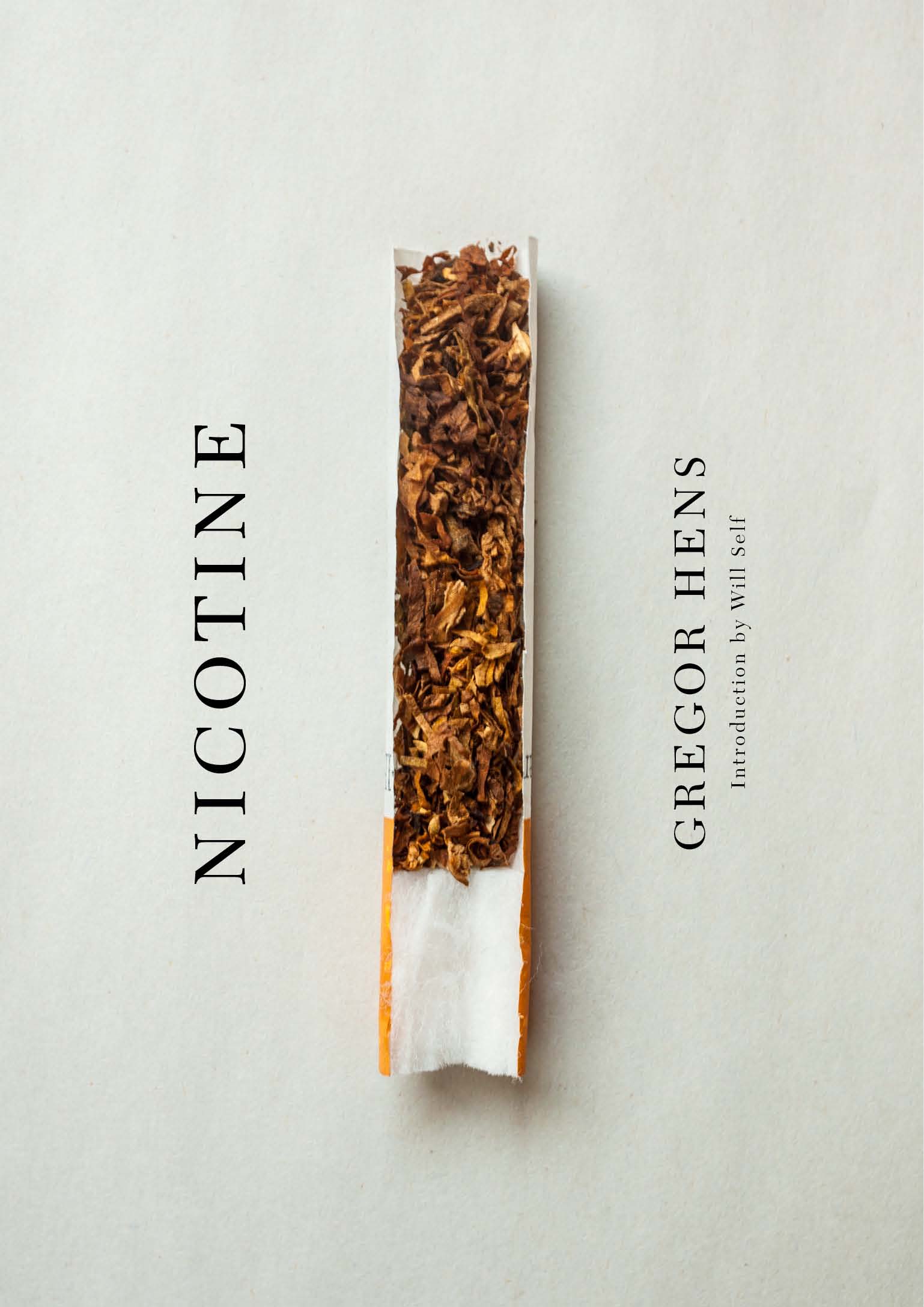

Nicotine, by Gregor Hens, translated by Jen Calleja, Other Press, 176 pages, $16.95

• • •

What makes a smoker an expert on addiction? The number of cigarettes smoked per day? The length of the habit? Would Albanian king Zog, who daily consumed ten packs of perfumed Turkish cigarettes, have more insight than Pope John Paul II, who purportedly limited his intake to three a day, one at the end of each meal? They were both cigarette addicts, if with vastly unalike levels of physical and psychological investment. Still, the difference is worth pondering, especially when it comes to writing about smoking. Most addictive behaviors today—drink, drugs, gambling, sex—that give rise to memoirs do so because those caught in their lair hit the proverbial bottom. They blew their house, or blew a stranger, or somehow or another did something to add to or effect the ruin of their lives. Smoking is the odd bird of the list: the catalysts to quit are varied and often lacking the conversion narrative of other addictive behaviors. Few give up a heroin habit as a New Year’s resolution.

Whatever the reasons for abandoning tobacco, the nicotine-addiction genre is palpably less dramatic on the page than its birds-of-a-feather degradations, no matter how much what Italian novelist Italo Svevo called the propensione al fumo feels downright literary in nature. Smoking, smokers like to think, is a habit well suited for contemplative moments, particularly those spent in company with a book, an aspect not lost on the German author and translator Gregor Hens in his memoir Nicotine. “I spent many years doing nothing but reading and smoking,” he observes of his cigarette adolescence. “Between the ages of thirteen and nineteen I read and smoked absolutely everything that I could get hold of.” Hens underscores the intimacy of the two activities, writing of his mother’s reading habits as they oddly fluctuated in tandem with her smoking. When her cigarette intake was small, her tastes in books turned to the heavyweights—Mann, Musil, Zweig. When she was depressed and chain-smoking, she eased up on the literary load and gorged instead on page-turners.

In this extended, diaristic essay peppered with Sebaldian photos and the names of forgotten Euro-brands, Hens writes philosophically about his own struggles to break the habit and his memories of a life spent in the long shadow of an extended family of big-league tobacco users. His aunt, a pensioner of a Bremen cigarette factory “that produced, among others, the market-leading light cigarette Lord Extra,” received as a stipend on her retirement two cartons of cigarettes each month, scheduled to last until either 2071 or her demise. (Despite the nico-goodies, she was a light smoker.) His brother’s first cigarette came via his grandfather, who offered him a Lux during a camping trip. But it is Hens’s mother and father who cast the longest shadows over his recollections. His mother introduced him to smoking when he was five; she gave him a slender little Kim cigarette to use as a punk with which to light some holiday fireworks. He of course inhaled. His father plowed through two packs of Ernte 23 every day, “each of those hinged jumbo packs” holding “forty cigarettes lying beneath silver paper evocative of a freshly ironed bedspread.”

It is Herr Hens’s addiction and its resolution in particular that haunt Nicotine and provide the most unsettling exception to an at times anodyne narrative. A technical expert in fire hazards and explosives, he decides to give up the habit spontaneously one day when he notices he has lit a new cigarette while another is still burning in the ashtray. The fact that his addiction had outstripped his conscious awareness of it offends his sensibility and the pride he takes in exercising his willpower. Hens is in oedipal awe over the ease with which his father masters his desires, and feels shoddy by comparison. The place of Hens senior in his son’s nicotine story gives an edgy energy to a memoir that elsewhere feels more casual than compelling. The jaunty introduction by veteran tobacco aficionado Will Self doesn’t help; it makes Hens’s ruminative reflections seem all the flatter.

Nearly a century ago, in the novel still best known in English as Confessions of Zeno, Svevo wrote the book on the addict’s paradox: How can one ever get over a habit if resolving to kick it ironically ensures that it will never go away? As formulated by his bumbling creation Zeno Cosini, whose farcical inability to quit smoking (or to quit quitting smoking?) underpins his neurotic personality, the terms of this addiction are: “Since cigarettes do me harm, I won’t smoke any more, but first I want to do it for the last time.” There is of course an insidious logic to Zeno’s idea of the Last Cigarette and one that I would wager the majority of smokers have to navigate when they give it up, but Hens demurs. It’s not that there’s such a thing, he argues, as that Last Cigarette and the smoke-free future that lies on its other side; rather, the Last Cigarette is always already a first cigarette, a relapse that often defeats the efforts of someone battling addiction. The “mellow hero” of Svevo’s novel, Hens writes, is certainly “already highly experienced in relapsing.” He adds, “Only those who have relapsed a few times truly know how powerful their addiction is.”

There’s a gentle comedy in Hens’s argument with Svevo, on par with the wit he uses to take on two other tobacco masters, Allen Carr and Mark Twain. (He finds it highly unlikely that the creator of Huck Finn ever actually said, “Giving up smoking is the easiest thing in the world. I know because I’ve done it thousands of times.”) Hens also offers the fetching image of a kind of Google map that identifies all those places—from Fun City-era New York to a quarry near Leverkusen-Schlebusch, Germany—that he’s ever lit up, matching them with all the brands he’s ever smoked. Tobacco, labeling, and landscape all combine with a snapshot immediacy, powerful and pleasant, that gives flavor and color to Hens’s discovery of the wider world, in all its variety, and to moments of great personal significance. If it’s hard to communicate to nonsmokers how physically and mentally difficult it is to quit, Hens’s memories of nicotine make it palpable to anyone why, even once you’ve stopped smoking, you’re never quite over it.

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU. He is the former president of the National Book Critics Circle. He was previously editor-in-chief of Bookforum and a senior editor at Artforum.