Eric Banks

Eric Banks

Portrait of a young neo-Nazi organizer: Sjón imagines a new villain into Iceland’s past.

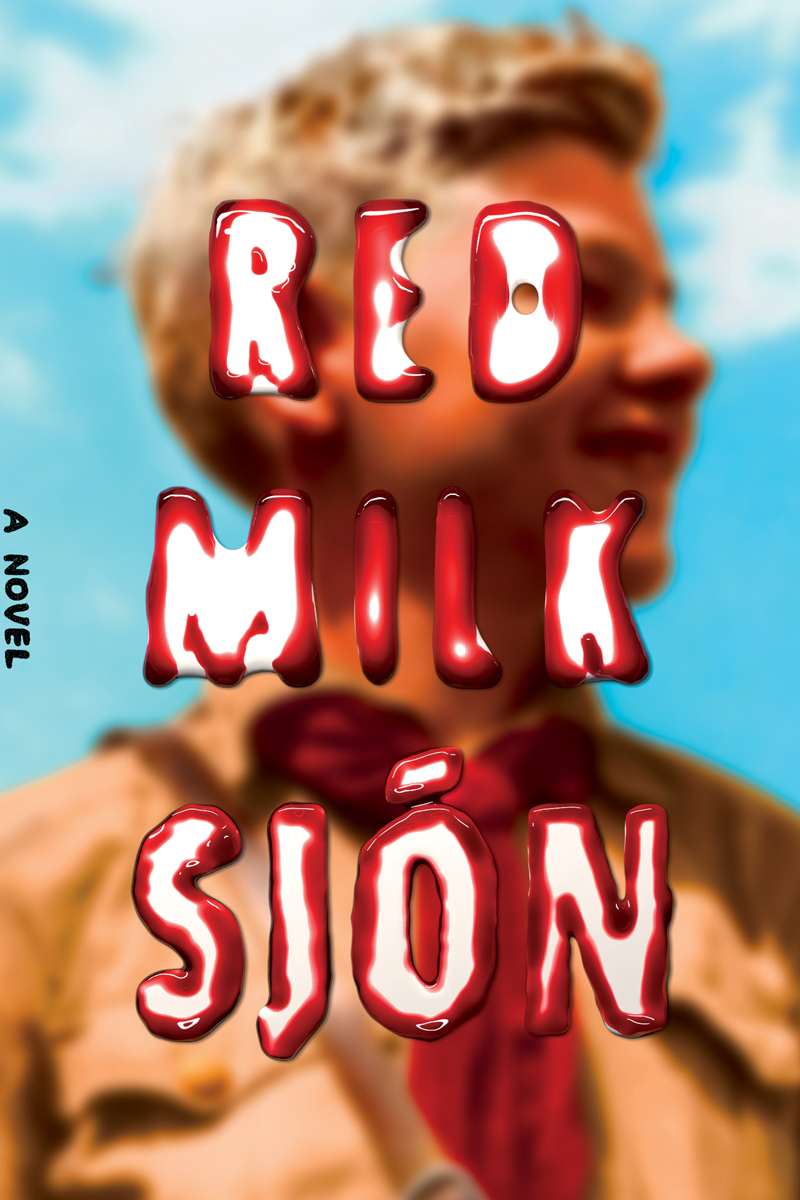

Red Milk, by Sjón, translated by Victoria Cribb, MCD, 148 pages, $25

• • •

In the unusual postscript to his newly translated Red Milk, the Icelandic novelist Sjón writes, “When I’m planning a new novel, I invariably begin by deciding what not to do as much as what needs to be done to create the book I’m aiming for.” In the case of this slip of a story, which narrates the short life of a certain Gunnar Pálsson Kempen, a shadowy figure who devotes much of his twenty-four years to organizing a minuscule neo-Nazi movement in his native Iceland as it emerges from World War II, the normally parsimonious Sjón has topped himself, chiseling his narrative down to its very armature. Red Milk takes its barebones form literally, stripping away everything it can to pursue an autopsy of its odious fictional character.

Restraint has always been a signature virtue of Sjón’s work, whether in the marvelous confection Moonstone (2013), a story of cinephilia and Spanish flu and a “boy who never was” in 1918 Reykjavík, or the comic entertainment The Whispering Muse (2005), which managed to combine a glimpse of Nordic life in 1949 and the mythical tale of the Argo, narrated through the strange voice of one Valdimar Haraldsson, erstwhile editor of the journal Fisk og Kultur. In the latter, Haraldsson expounds on his pet theory—in his words, the “link between fish consumption and the superiority of the Nordic race”—a concoction Sjón converts into ironic fodder for a funny little novel.

Although it shares a historical time frame with The Whispering Muse and is mixed from certain of the same dubious spirits, Red Milk is an entirely different cocktail. Written in three sections—the second comprising a one-sided epistolary novel as Gunnar attempts to foment his movement—and translated seamlessly by Victoria Cribb, Sjón’s story examines an otherwise unremarkable and largely featureless character, based loosely on a real-life figure who died young of cancer. (The original Icelandic title, Blond Hair, Gray Eyes, gives a stenographic taste of Gunnar’s banality.) Taking place in an Iceland roiled by violent demonstrations involving both the left and the right against NATO and the establishment of a US military presence (if you fly to Iceland, you’ll land at Keflavík, built as an American air-force base), the novel touches on the somewhat ghostly role the island played in the underground network of international neo-Nazism in the 1950s. Cameos include George Lincoln Rockwell, the head of the American Nazi Party who cut his fascist teeth while serving as a pilot in Iceland; and the murky figure of the French Nazi occultist Savitri Devi, who rhapsodized over the devastating eruption of Mount Hekla during her time on the island. If English and American writers from William Morris to Michael Lewis have taken Iceland as a palimpsest for any number of ultima Thule fantasies, it has held a no less spectral fascination for the extreme right as a kind of cradle of Aryan culture. Rereading Letters from Iceland, W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice’s giddy record of their 1936 visit, it’s startling once again to come across the passage in which Auden recalls running into the brother of Hermann Goering at a Reykjavík hotel.

Rockwell, Devi, et al. are fringe figures (whatever “fringe” still means in the age of QAnon, Replacement Theory, and Anders Breivik), and so is Gunnar: his life is only fleetingly colored in, a curious example of where Sjón attempts to balance the creation of a vile protagonist and his resistance to provide empathy or justification to a character who would happily will the death of a great number of those around him. We never learn anything terribly revealing about what made him into what he became. Sjón actually begins his story by killing off Gunnar, whose just-expired pajama-clad corpse is discovered on a metro train in London, with directions to an English neo-Nazi enclave, a thick wad of Icelandic krónur notes, and a scrawled swastika in his coat pocket. Written as if it were the opening lines of a crime novel, the scene-setting is a master case of indirection: there is a mystery here, in Gunnar’s embrace of the neo-Nazi cause, but it is one that the author will steadfastly refuse to unlock.

Instead, he provides an almost cinematic swirl of set pieces: the glimpse of Gunnar’s father, who anxiously monitors the radio and news of the war nightly in his small den off the bedroom, switching out the white lightbulb each evening with a red one so as not to keep the family awake; the cycling–cum–German-language club that embarks on group outings along Reykjavík’s northern shore to a chorus of bells and a crowd of admirers; a distant quisling aunt disembarking in Iceland after the German surrender in Norway, her shorn head covered by a scarf. When a dark figure (Sjón lets it hang that this might in fact be Devi) is discovered by a young Gunnar at a meeting of a local choral society, he catches the glimmer of her filigree brooch, decorated by tiny swastikas, on her blue-and-white shawl. The landscape of Red Milk is built of such lightning bursts of strangely sharp detail, where the use of colors stands out. It’s a subtle stroke in a novel whose quiet complexity can at first seem elusive: even though the book is in a sense a flashback from Gunnar’s moment of death in his early manhood, this is a landscape proper to a child’s imagination, dreamlike but solid, with all the pronounced lucidity and wild agency that objects and colors assume.

Red Milk is no less subtle—or complex—in its caution with language. Gunnar’s voice is set to mute throughout the novel. He is represented almost entirely through the missives (letters, broadsheets) he sends from behind a PO box in Iceland, a kind of time capsule of how now-fascist thought was disseminated like brown-bag porn in the quaint days before social media. The prose on offer in the correspondence, mostly an unctuous mix of bilious praise and anti-Semitic party-speak, contrasts with the very small number of times Gunnar actually opens his mouth in the novel—a mere nine or ten lines, mostly single sentences in response to another character. The effect is to amplify the extreme sense of isolation—the isolation of the fanatic, the isolation of Icelandic society—and unknowability that Red Milk conjures. Toward the end of his life, in a sick ward in Britain (where the white-coated doctors examine him “behind leaded glass to protect them from the gamma rays”), a visitor tells him, “That’s what you Icelanders are like. Once you go home, you disappear into thin air.” Throughout Red Milk, Gunnar is barely there, yet unbearably present. In this short and bleak novel, Sjón makes us think again about what empathy can—and frequently enough simply can’t—achieve.

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at the NYPL. He is the former president of the National Book Critics Circle. He was previously editor-in-chief of Bookforum and a senior editor at Artforum.