Thomas Beard

Thomas Beard

From destructivist assemblage to the poetry of Super 8: an expansive series examines Latin American avant-garde film.

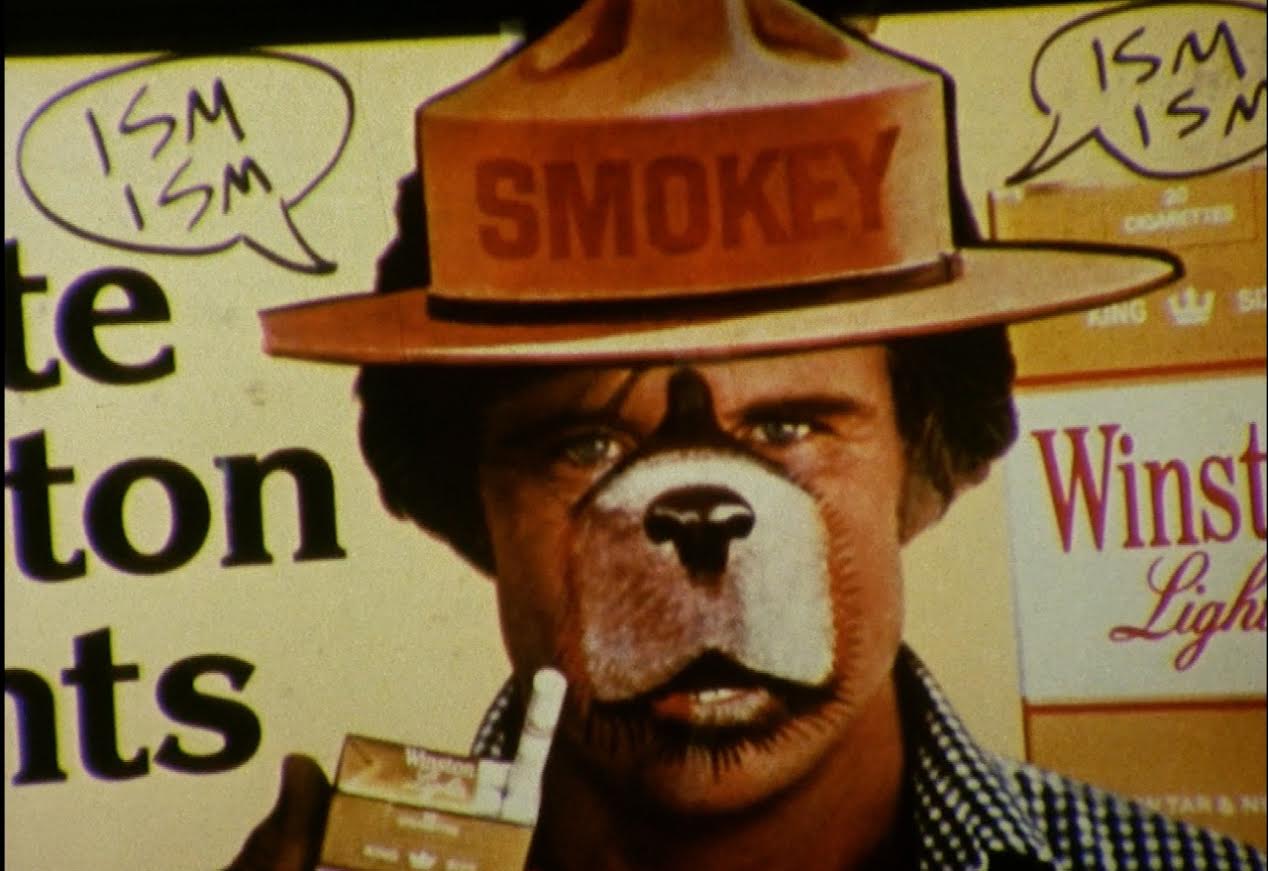

Manuel DeLanda, Ism Ism, 1979. Image courtesy Manuel DeLanda.

Ism, Ism, Ism: Experimental Cinema in Latin America, through January, 2018. For full program and venues: ismismism.org

• • •

Narratives of film’s evolution as an art form often make fleeting reference to the medium’s most experimental entries, if attention is paid at all. So when the task of chronicling the avant-garde is taken up, the omissions are especially notable; elided works are effectively consigned to the margins of an already marginal enterprise, and run the risk of vanishing altogether. Forgetting, in this scenario, is the rule, not the exception.

Still, for audiences interested in charting a course through the outer limits of the moving image, the past decade has been witness to an extraordinary sequence of recuperative efforts, of publications and related film programs highlighting artists who might have otherwise flirted with oblivion. Radical Light, for instance, examined the varied terrain of adventurous production in the Bay Area in the second half of the twentieth century, while Alternative Projections considered rare species of SoCal moviemaking that bloomed in the shadow of Hollywood between 1945 and 1980. Shoot Shoot Shoot looked back on the avant-garde activity that effloresced around the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative in its first decade (1966–76), and, in New York, Anthology Film Archives recently unveiled a kind of update to its own much-debated repertory cycle “Essential Cinema” with “Re-Visions,” showcasing filmmakers like Peggy Ahwesh and Ericka Beckman, who emerged in the fifteen years after the institution’s internal canon was cemented in 1975.

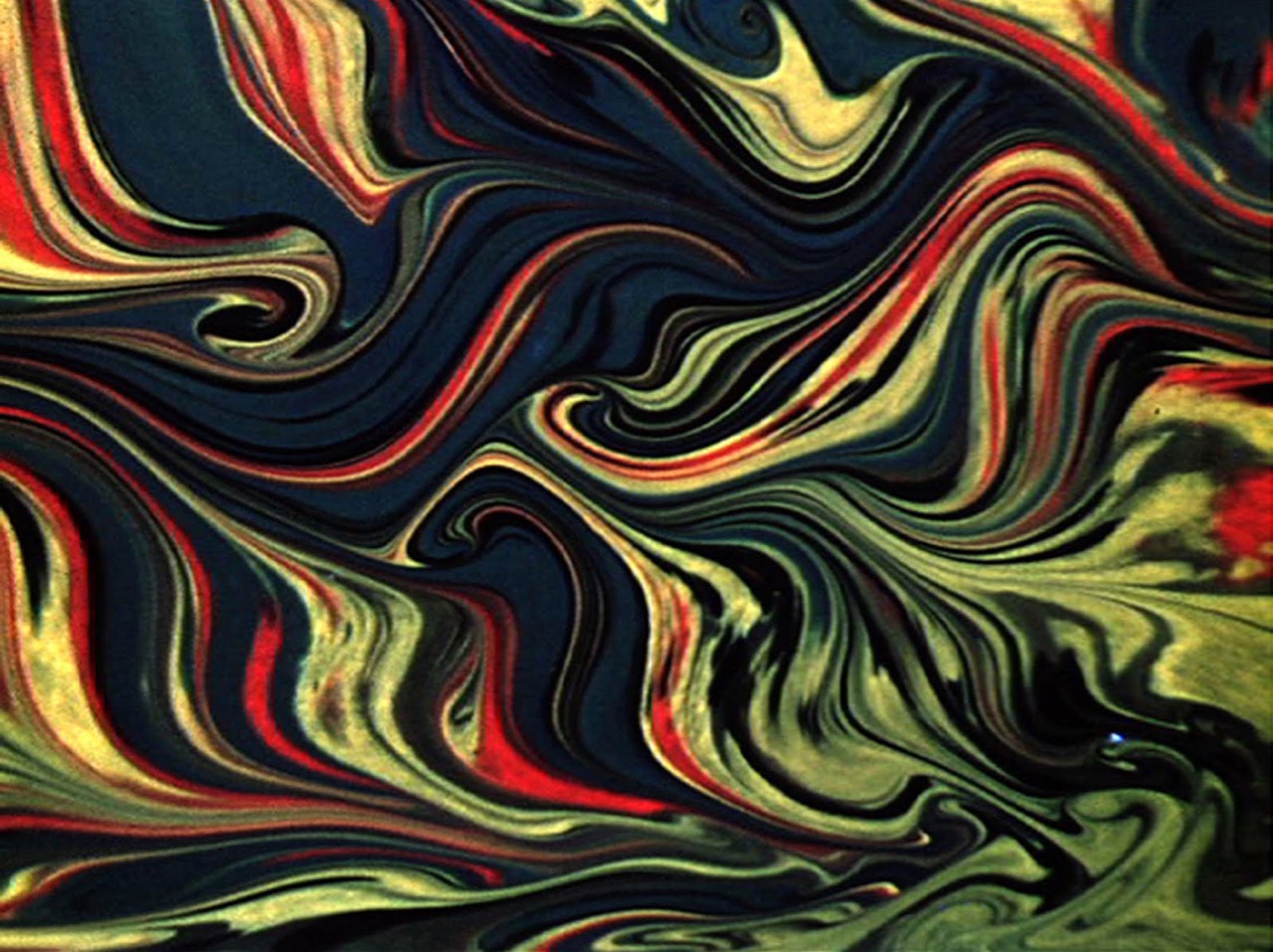

Lydia García Millán, Color, 1955. Image courtesy Lydia García Millán.

And yet, despite these impressive and heartening developments, significant lacunae remain. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the story, little-known to Anglophone moviegoers, of avant-garde film traditions in the Global South. Closing the gap considerably is Ism, Ism, Ism: Experimental Cinema in Latin America. Conceived in conjunction with the most recent iteration of the multi-venue, Getty Foundation-led mega-show Pacific Standard Time, this ambitious and revelatory project, overseen by Jesse Lerner and Luciano Piazza, has taken shape as both a film program and a collection of writings. The series, hosted by Los Angeles Filmforum and partnering venues, is expansive, unfurling over the course of five months, and boasts a terrifically varied lineup, one that operates with a thoughtfully elastic definition of “experimental” and ranges from the resplendent, marbleized abstraction of Lydia García Millán’s Color (1955) to the indigenous struggles documented in the Chiapas Media Project’s The Land Belongs to Those Who Work It (2005). Equally multi-faceted is the bilingual companion publication, which ensures that the ideas animating Ism, Ism, Ism will reverberate far beyond the West Coast. Its editorial conception is significant, containing not only a substantial array of new scholarship—María Belén Moncayo’s profile of globe-trotting queer dandy Eduardo Solá Franco and his surrealist-inflected, small-gauge studies of tragic classical themes is particularly memorable—but also a panoply of primary documents, like Gabriel García Márquez’s proposal, from 1960, for a film institute in Barranquilla, Colombia, and a 1980 catalog excerpt by the organizers of the Fifth Caracas Super 8 Festival (the “Cannes of Super 8”).

Chiapas Media Project, The Land Belongs to Those Who Work It, 2005. Image courtesy Chiapas Media Project.

Part of what makes Ism, Ism, Ism so vital an initiative is the way it rescues certain works that came dangerously close to being lost—Federico Windhausen mentions in his essay on Umbrales (Thresholds, 1980), Marie Louise Alemann’s impressionistic portrait of cruisey male interactions, that he retrieved the film from the director’s closet, tucked away next to her home movies. Elsewhere the volume foregrounds provocative and novel approaches to some of experimental cinema’s key idioms. In his contribution, Lerner notes that the major surveys of found footage filmmaking make no mention of such practices in Latin America, and offers, as an alternative, a question: “How different would a history and theory of found footage filmmaking look if written from a Latin American perspective?”

Marie Louise Alemann, Umbrales (Thresholds), 1980. Image courtesy Katja Alemann.

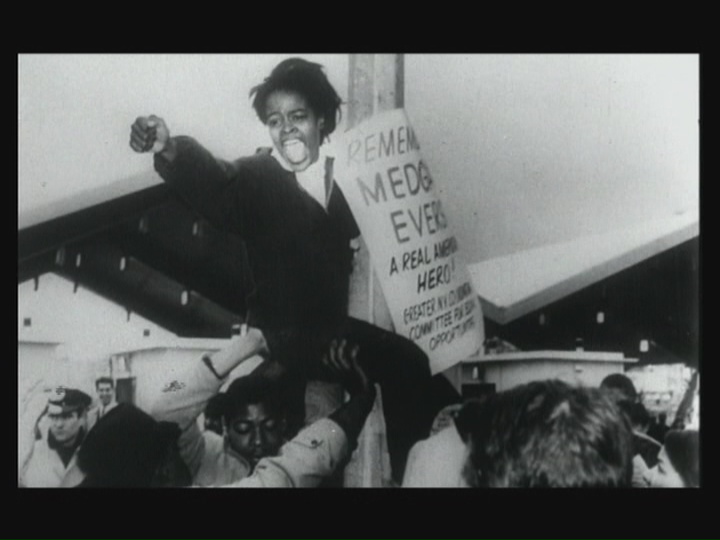

Whereas most accounts proceed from the oneiric reorderings of Joseph Cornell, such as his star-gazing Rose Hobart (1936), Lerner finds an originating moment of cine reciclado in Rafael Montañez Ortiz and his destructivist assemblages, as well as in Santiago Alvarez, whose film Now! (1965) blasts forth as a machine-gun montage of violent imagery from America’s civil rights era while Lena Horne provides a soaring soundtrack with her eponymous protest anthem, sung to the tune of “Hava Nagila.” A brief but incendiary dispatch from post-revolutionary Cuba, Now! simultaneously evinces multiple registers of “appropriation” and serves as a timely reminder that this now-embattled term can sometimes signal neither theft nor domination, but rather solidarity and more. Indeed, undergirding Lerner’s argument is the metaphor of anthropophagy, which has been central to numerous political and aesthetic discourses in Latin America since it was advanced in Oswald de Andrade’s 1928 “Cannibalist Manifesto.” Against the backdrop of colonialism’s violent legacies, we witness what Lerner describes as “filmmakers who chew up the movies of others and use these fragments to nourish their own films.”

Santiago Alvarez, Now!, 1965. Image courtesy Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos.

Pablo Marín, in his perceptive catalog essay on Argentine directors like Claudio Caldini, Narcisa Hirsch, and Jorge Honik, likewise challenges the received understanding of one of experimental cinema’s crucial modes, Super 8 filmmaking. Unmooring the format from its typical associations—as a cinematic sketchbook, or the stuff of amateurism and home movies—he presents instead a diminutive tool that, paradoxically, contains within it the source of boundless poetic potential, “a small philosophical machine that can be considered the ultimate—and in its ubiquity the most unbridled—crystallization of analog audiovisual thought.” Deployed in the service of this line of reasoning is a potent analogy for Super 8: the Aleph, drawn from a Jorge Luis Borges story in which, from a single, tiny point in a Buenos Aires cellar, the entirety of the universe may all at once be perceived.

Taken as a whole, Ism, Ism, Ism, even with its prodigious scope and the manifold sensibilities suggested by its title, is finally less like the Aleph of fiction than aleph the letter, the first of the Hebrew alphabet. Said another way, what we here encounter is not a fantasy of total vision, but something infinitely more exciting: a beginning.

Thomas Beard is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, and a programmer at large for the Film Society of Lincoln Center. He was the co-curator for the cinema programs at the 2012 Whitney Biennial and Greater New York 2010 at MoMA PS1, and has organized screenings for Artists Space, BAMcinématek, the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, the Centre Pompidou, Harvard Film Archive, the Museum of Modern Art, and Tate Modern.