Thomas Beard

Thomas Beard

Rhythms of sound, image, and silence: in the filmmaker’s experimental montages, an exploration of ambiguity and narrative tension.

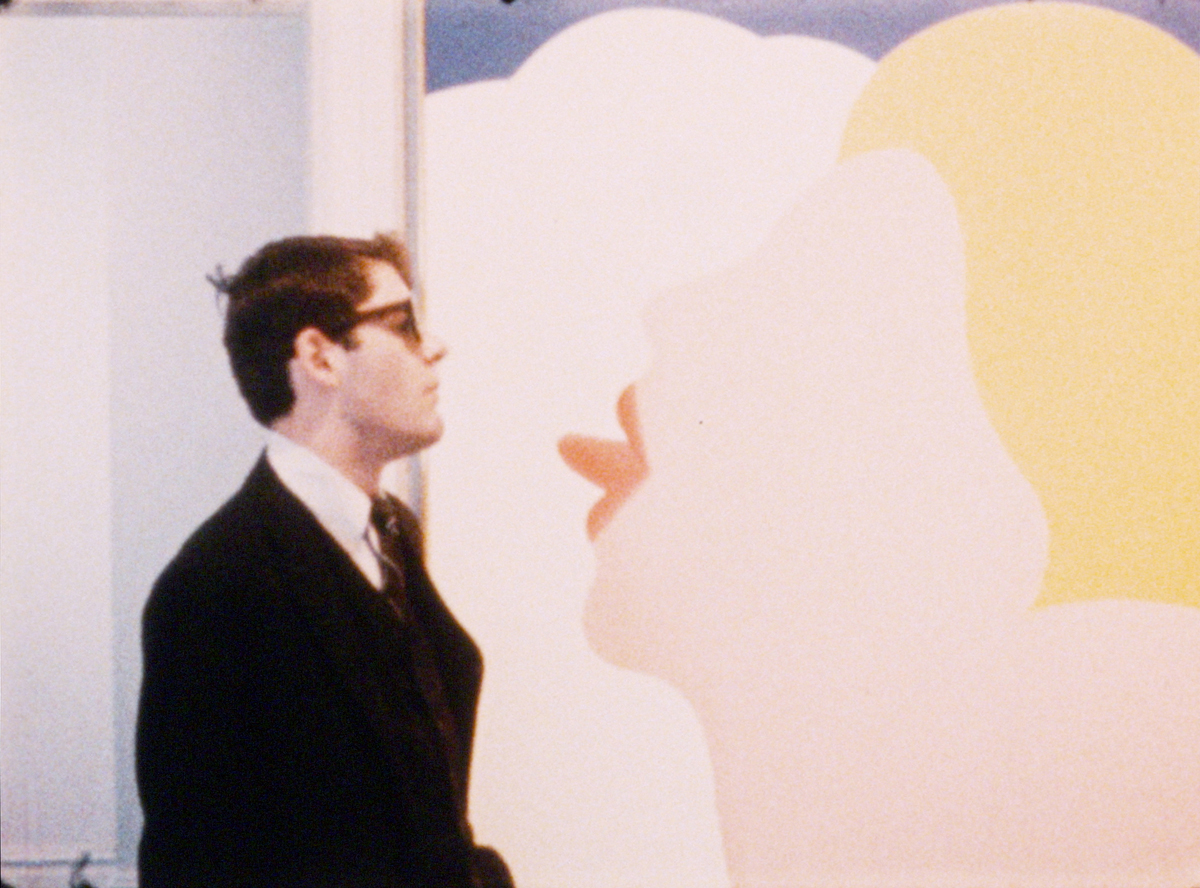

Still from Where Did Our Love Go? Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

“The Experimental Narratives of Warren Sonbert,” organized by Ron Magliozzi and Jon Gartenberg, with Carson Parish, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through May 19, 2023

• • •

Warren Sonbert was not a diary filmmaker. Or, not precisely. He found the label rebarbative when applied to his own work, which it often was, though this designation should come as no surprise. After all, he and his Bolex were the one common denominator throughout his cinema. His movies drew from the world as it unfolded around him, frequently populated by people he knew, places he visited, and his earliest efforts have the feel of avant-garde home movies. He may have debuted as a diarist, but he soon became something else entirely: a practitioner of one of the most distinctive forms of montage the medium has yet produced.

Still from Amphetamine. Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

Sonbert was precocious from the outset. He started making films while a student at NYU, but his true education took place inside Lionel Rogosin’s Bleecker Street Cinema, which he was already haunting as a teenager, ultimately serving as an editor of its in-house movie magazine, NY Film Bulletin, before he reached his twenties. From his very first film, Amphetamine (1966, with Wendy Appel), a tender and graphic study of gay speed freaks, a sensibility began to coalesce as he chronicled his youthful, bohemian milieu. Here, and in films like Where Did Our Love Go? (1966), Hall of Mirrors (1966), and The Bad and the Beautiful (1967), he explored the aesthetic possibilities of the handheld camera, a frame that moves like the body, following a path blazed by Marie Menken. He also embraced a formal vocabulary, expanded by Stan Brakhage, that included those qualities the dominant cinema would reject as “mistakes” (flare-outs, over- and underexposure, film jittering in the gate), and layered his scenes, as Kenneth Anger had a few years prior in Scorpio Rising (1963), with the pop music of the day (girl-group sounds predominate).

Still from The Bad and the Beautiful. Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

When crowds flocking to Sonbert’s screenings at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in 1968 seemed to rival those of Warhol’s crossover hit Chelsea Girls, even the trades took notice. Box office, reported Variety, was boffo. As the decade came to a close, changes were afoot in Sonbert’s life and art alike. He decamped for San Francisco and, with Tuxedo Theatre (1969), his films fell into a complete and total silence. And yet they became more musical still, only now their rhythms were purely visual, progressing inside shots as well as across them. It was an approach shared by Brakhage, who famously quipped, “I’m not against sound film, though I rather think of it as grand opera.”

Still from Carriage Trade. Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

In the case of Sonbert, silent film was a grand opera. He was, in fact, a noted opera critic, frequently organizing his peregrinations around the performances he was tasked with writing about, and arranged his works into Mozartian key structures. Carriage Trade (1972), his longest and best-known film, was in E-flat major (or, as Sonbert put it: “broad, epic, leisurely, maestoso”). It’s also emblematic of his mature style, of what philosopher Noël Carroll would later describe as “polyvalent montage.” A globe-trotting affair, Carriage Trade was shot on four continents over the course of six years. Save for a handful of moments, as when we clock the Taj Mahal or Venetian gondoliers, it’s difficult to locate where, exactly, we are passing through as the movie’s currents carry us along, but no matter. What we’re watching is not a travelogue so much as a complex, nonlinear image network.

Still from Carriage Trade. Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

Though individual shots in Carriage Trade are quite striking—I think often of a particular pan, arcing across a cluster of rooftops covered with cowhides drying in the sun—their character is always associative, shaped not only by those images that immediately follow and precede them, but also by the entire sequence in which they are embedded. So a shot might be bracketed by other, “neutral” shots, typically absent a human figure, allowing it a bit of breathing room, while serving variously, and sometimes simultaneously, as a complement or point of contrast to those further up and down the reel, both on the level of their content as well as their design. An elaborate web of correspondences thus emerges between different shot lengths, between different film stocks, between the movement of the camera and the movement within the frame, between the action in the foreground / middle ground / background, between shifting color schemes.

Still from Carriage Trade. Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

“The job of editing,” Sonbert explained, “which distinguishes film from theater or simple (minded) photography, is to balance a series of ambiguities in a tension-filled framework.” In the drama of his theory of film syntax, Sonbert casts Sergei Eisenstein as the villain, he who dismissed Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Eye in favor of a Kino-Fist. One could take the iconic sequence from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925), for instance, with its rapid alternation between slaughtered workers and an abattoir, as the antipode of Sonbert’s imperative; whatever the strengths of this episode (and there are many), it does not, shall we say, nurture ambiguity.

Still from Friendly Witness. Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

But we encounter heroes in this production, too, like Douglas Sirk and Alfred Hitchcock, two of Sonbert’s signal influences. From the former he learned the potential of mise-en-scène, of the way architecture defines those who inhabit it, and like Sirk he could take an unsparing view of the rituals and mores of the society in which he lived. Through the latter he understood how a movie’s structure might implicate the viewer in the order of its moral universe, as well as suspense, since one of the most thrilling qualities of a Sonbert film is never knowing where, from moment to moment, we’ll next land. It’s tempting to say that watching a work by Sonbert is like watching a Hitchcock film, only now the veil of plot and its exigencies has been lifted, leaving behind a cast of thousands and the ornate formal interplay that binds them together.

Still from Whiplash. Courtesy Gartenberg Media Enterprises.

Sonbert’s third act, when music came rushing back to his cinema in Friendly Witness (1989), would be his last. This reemergence of audio, however, following two decades on mute, is not the volte-face one might imagine. The soundtracks become more varied (who else could pull off a pivot from Lohengrin to Laura Branigan?), and, crucially, function less as embellishments than as yet another contrapuntal element within increasingly intricate compositions. The scene from this phase that I find myself recalling again and again is the bullfight from Whiplash (1995/97), his final statement before succumbing to AIDS-related illness at age forty-seven. Sonbert was a matador, stylishly guiding his films’ relentless charge, his art a spectacle of uncertainty, and of grace.

Thomas Beard is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for cinema in all its forms.