Thomas Beller

Thomas Beller

“Fuck filial piety”: in his essay collection, Wesley Yang confronts the Asian American experience.

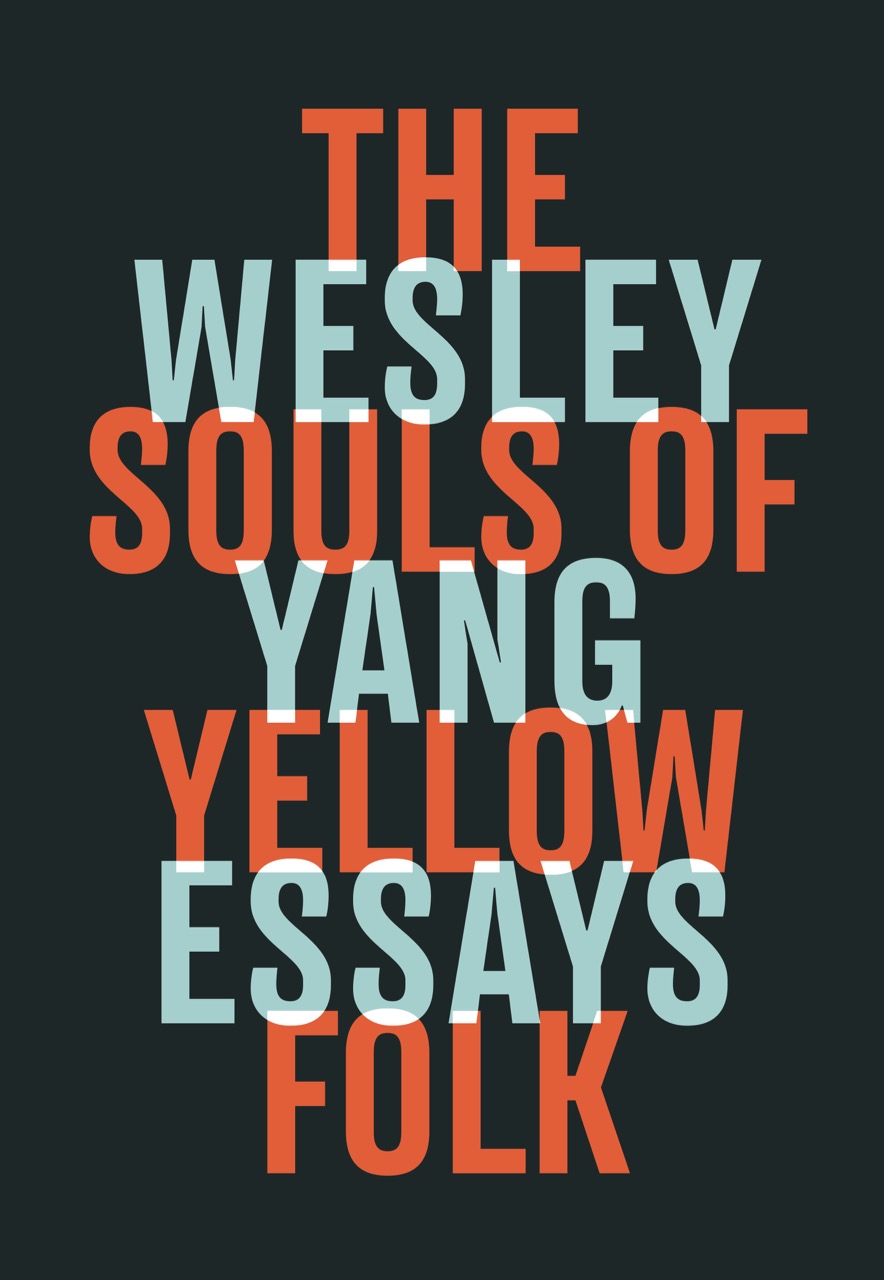

The Souls of Yellow Folk, by Wesley Yang, W.W. Norton, 215 pages, $24.95

• • •

I first encountered Wesley Yang in 2005 when he wrote a New York Observer piece about the circuitous publishing fate of Sam Lipsyte’s third book, the novel Home Land. (This was back when I was editing Open City Magazine, which had published Lipsyte’s first story collection.) I’ve followed Yang since; his byline elicits immediate interest from me and, often, joy. The Souls of Yellow Folk—its title a provocative riff on W.E.B. Du Bois’s classic treatise on America’s “color line,” its contents more than a decade’s worth of previously published essays—gave me an occasion to scrutinize why this is so.

On the face of it—a loaded phrase in this context—what I most enjoy is Yang’s lovely python style of writing and thinking. He seems to have imbibed everything related to his topics at the cost of great effort. But his prose unfurls in a mode of languorous deliberation. Present throughout The Souls of Yellow Folk is the question of who works hard, who takes it easy, and how the rewards for this work are portioned out in America. Money is part of it, but it’s a symptom. As Yang states repeatedly, there is no higher achieving cohort in America, if earnings and education are the measure of happiness, than Asian. And yet.

“Paper Tigers”—one of the tour-de-force pieces in the book, and the one that takes on most directly the contradictions of Asian accomplishment and the mythology of meritocracy—contains a phrase that has stayed with me since I first read the piece in New York magazine in 2011: “brutal labor.” Yang quotes law professor Tim Wu on his first years of work after law school: “ ‘There was this weird self-selection where the Asians would migrate toward the most brutal part of the labor.’ ” Elsewhere in that same piece Yang relays a quote from an instructor at one of the “cram schools” that so many Asians in New York City attend in the hopes of scoring high enough on the entrance exam to be admitted at the city’s top public schools, such as Bronx Science and Stuyvesant. “ ‘Learning math is not about learning math,’ ” says the instructor. “ ‘It’s about weightlifting. You are pumping the iron of math.’ ”

“Paper Tigers” is a great example of the positive results derived from pumping the iron of reporting. And yet Yang hates the expectation that he should embody this practice, and one of the pleasures of the book is the way that amid his sophisticated tone and scrupulous reporting, he often gobs at his readers as though he were in the Sex Pistols.

“Let me summarize my feelings toward Asian values,” he writes in “Paper Tigers.” “Fuck filial piety. Fuck grade-grubbing. Fuck Ivy League mania.” The list goes on. Then he asks, “If it is true that they are collectively dominating in elite high schools and universities, is it also true that Asian-Americans are dominating in the real world?”

“Paper Tigers,” and The Souls of Yellow Folk as a whole, is an examination of the reasons, external and internal, that make the answer to this question “no.”

The book’s introduction is mostly an introduction to the first piece in the collection, called “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho.” (The man who perpetrated a mass shooting at Virginia Tech in 2007.) “More than a decade ago, an editor at the literary journal n+1 asked if I wanted to write about the largest mass murder in American history, which had occurred a few days previously at a college in Virginia. I resented the implication of his request. The implication was that there was something about that episode that would be particularly salient to me. I resented the implication because it was true.”

For a moment it seemed like Yang’s book might have a structure like Norman Mailer’s 1959 essay collection, Advertisements for Myself, in which each piece has its own preface, a story of the story. This is not the case. But it turns out there are other reasons to associate Yang with Mailer. The two authors are preoccupied by the subject of male satisfaction—both sexual and spiritual, though really, the distinction becomes vague at some point. There is no orgone box in Yang’s book, but his subjects, including himself, are often yearning for something that will radically transform the experience of being a man.

Not all of the pieces here deal directly with the Asian American experience. There are long, intricate profiles of internet activist Aaron Swartz and historian-essayist Tony Judt, a gloriously droll riff on the era of MTV’s Total Request Live, and a deep dive into the world of pickup artists learning the Game—an absurdly misogynistic and artificial technique that I have always thought of as pathetic, even though it apparently achieves the immediate and narrow goal of getting many men laid who would not otherwise have this experience, and has therefore become a global phenomenon. In “Paper Tigers,” most of the men who are paying up to $1,450 for their pickup tutorial are Asian, and they all tend to feel “stifled, repressed, abused” and that they “do not matter.” Misunderstood men. Invisible men. Yang, present on the scene to report, sees his reflection in some of these guys, too, and falls a bit headlong into the whole thing.

Another overlap between Yang and Mailer is that they are both excellent reporters who nevertheless find the most compelling evidence for their ideas in the mirror:

“Sometimes I’ll glimpse my reflection in a window and feel astonished by what I see. Jet-black hair. Slanted eyes. A pancake-flat surface of yellow-and-green-toned skin. An expression that is nearly reptilian in its passivity.” This is the opening of “Paper Tigers.” Of Seung-Hui Cho, he writes: “A perfectly unremarkable Korean face—beady-eyed, brown-toned, a small plump-lipped mouth . . . It’s not an ugly face, exactly; it’s not a badly made face. It’s just a face that has nothing to do with the desires of women in this country . . . Seung-Hui Cho’s is the kind of face for which the appropriate response to an expression of longing or need involves armed guards.”

Though Yang pumps the iron of reporting, his pieces have a bit of dream state about them. I find the self-conflicted elegance of his prose to be a delight. We have heard so much about the incursions of the essay into fiction, but here we have the opposite, reported essays that often levitate into that fiction feeling on the strength of the author’s voice and their sharply observed character studies. The most significant character being studied is the intellectually curious, defiant, judgmental, often tormented, conflicted yet wonderfully coherent guy named Wesley Yang.

Thomas Beller is the author of four books, most recently J.D. Salinger: The Escape Artist, which won the 2015 New York City Book Award for biography/memoir. His fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, the St. Ann’s Review, Ploughshares, and the New Yorker. A founder and editor of Open City Magazine and Books from 1990 to 2010 and the website Mrbellersneighborhood.com, he is currently an associate professor at Tulane University.