Hannah Black

Hannah Black

In his new novel, Caryl Phillips channels Jean Rhys and

mid-twentieth-century England.

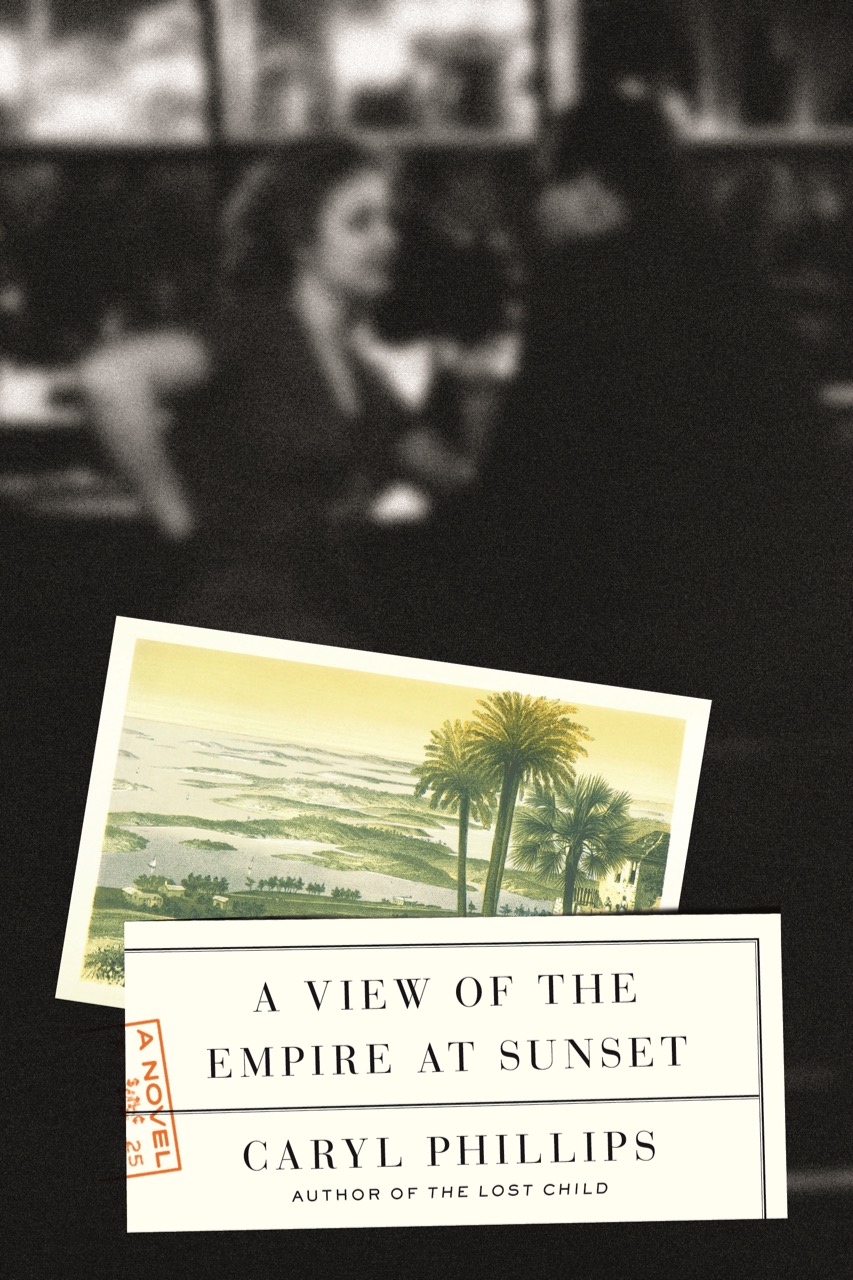

A View of the Empire at Sunset, by Caryl Phillips, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 324 pages, $27

• • •

To see the electric disturbances under the quiet surface of Caryl Phillips’s new novel, we have to go back to Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966). The latter made a breathtaking intervention into the canon of English literature, imagining a Jamaican prehistory for Bertha Mason, the famous woman in the attic in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. In A View of the Empire at Sunset, Phillips performs a somewhat similar procedure on Rhys herself, assembling the facts of her biography into a fictionalized portrait.

Brontë wrote Bertha Mason as an almost supernatural barrier between Jane Eyre and the promise of social mobility through marriage. Before her attic existence reduced her to a cipher, Mason was the Caribbean-born daughter of a white family enriched by the plantation economy, a background that left her too mentally unstable—according to her husband’s judgment—to have any kind of social existence at all. The death of Bertha, with her messy past and unassimilable pain, is a convenience that puts delicate, pale Jane finally in a position to marry Bertha’s husband, the man of her dreams.

The reason that Rhys was able to see through the tiny window of Brontë’s passing mention of Jamaica into the relation between colonial center and brutalized periphery is easy to grasp. She herself was born in Dominica to white parents, and her early life was marked by the characteristic repression, envy, and race-hatred that fuels white colonial life. She picked up the thread left dangling by Brontë and rewrote Mason as a woman who, faced with the contradictions and violences of a colonial childhood, was sensitive enough to do the right thing and go mad. Wide Sargasso Sea subjects the intricate etiquettes of the Victorian novel, its delicate intrigues and portrayals of refined sensibilities, to the shock of exposure to its practical, economic, and social foundation: slavery, the plantation economy, and colonial extraction. Set in the immediate aftermath of the formal abolition of slavery in Jamaica, the book explodes the narrow complacency, itself full of suffering, of Brontë’s world.

Phillips too has dedicated himself to bringing expression to the heavy silence surrounding the slaving and colonial foundations of British wealth: among his previous novels are Cambridge (1991), which describes an English heiress’s visit to her father’s island plantation, and The Final Passage (1985), the story of a black Caribbean family’s relocation to England in the 1950s. His oeuvre describes the contours of the Atlantic triangle that, with different intensities at different historical moments, displaced millions of people from Africa to the Americas and Europe and threw us all differently into the corrosive soup in which we now swim. Phillips, like Rhys, has lived a life explicitly connected to this extraordinary rendition. He was born in St. Kitts and his family moved to England when he was a baby, taking their place in the mass migration of people from the islands to their legislative center that is one of the most important geneses of the black community in the UK. Phillips narrates Rhys’s journey as she enacts a white variation on this story, born English in the Caribbean and sent as a teenager to an England that never becomes home.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm has described the Caribbean as a “curious terrestrial space station” inhabited by “fragments of various races, torn from the worlds of their ancestors and aware both of their origins and of the impossibility of returning to them.” Perhaps the metaphor strains reality by imagining white people living in the Caribbean as fundamentally sharing a condition of life with the people they are there to exploit. Nevertheless, whatever partial truth there is in Hobsbawm’s construction is illustrated by Phillips’s complex sympathy with Rhys. Like Rhys’s Caribbean intervention into Brontë’s English drama, A View of the Empire at Sunset is an act of homage as well as critique. Phillips, always a measured and careful writer, here mimics Rhys’s precise itemizations of the deprivations and humiliations of everyday life. His Rhys seems to have lost some of the wit and fury of the Rhys we know from her own novels, perhaps because it is hard for even a highly skilled pastiche to replicate the subtleties of a brilliant original, perhaps because Phillips wanted to give us a Rhys with the veil of her talent stripped away, a Rhys who exists at exactly the minute and trivial scale of middle-class English life—and most likely both.

To her white English contemporaries, Rhys was exotic and problematic because of her proximity to the black Caribbean; to Phillips, Rhys is the scion of a class of overseers, distinguished only by the aberration of her talent and insight. He borrows her own technique of cold precision and uses it against her, a complicated act of love. This Rhys, although repelled by and alienated from her peers, is unable to transcend the limits of her race and class—or perhaps her acceptance of these limits, like the mental illness of the woman in the attic, can be read as an ethical capitulation, an acceptance of her absolute difference from the black island she longs for.

Rhys lent her real biography to a fictional avatar to reinscribe an experience of the Caribbean back into the English canon; Phillips uses a fictionalized version of the real-life Rhys to present a Caribbean view of mid-century England. This England is intensely, overwhelmingly drab and devoid of pleasure; bourgeois life unfolds as a series of bleak affairs with sad lovers and loveless interactions with family and friends, all unvarnished by any deep sense of self or history. Phillips’s gray England has been drained empty of meaning by its disavowal of its colonial existence; its energies are wasted on the struggle of its middle classes to preserve their vapid identity against the onslaughts of class, race, and gender antagonisms, all of which are whenever possible politely ignored. While the black servants and neighbors of Wide Sargasso Sea present the white protagonist with opportunities for self-hatred, envy, or identity crisis, the white lower classes who Phillips makes the background of A View of the Empire at Sunset are almost invisible from the fictional Rhys’s point of view, or deployed only as objects of fantasy. One of the few glimpses of loving feelings in Phillips’s novel belongs to a scene in a pub in an impoverished area, where Rhys, dragged there by yet another inadequate but wealthy boyfriend, watches a couple dancing and imagines that they find in each other a respite from the hardships of their days.

The novel’s title riffs on a figure of speech expressing the geographical scale and implying the immortality of an empire. The triumph of liberation struggles in the Caribbean and elsewhere has given the lie to this and shown once more that it is oppressed people’s striving to discover something new about freedom on which the sun never in any sense sets. Rhys began writing Wide Sargasso Sea somewhere around 1945, as the British began a chaotic process of decolonization. In the years of the production of Phillips’s novel, the political cataclysm known as Brexit—partly fueled by a perverse nostalgia for empire—has rebirthed imperial ghosts, back this time as farce. The feeling of homelessness experienced by Phillips’s meticulously imagined Rhys obliquely echoes the epidemic of loss that imperial ambition let loose upon the world.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer from the UK. She lives in New York. She has previously written for Artforum, the New Inquiry, Afterall, Texte zur Kunst, and a number of other publications. Recent exhibitions include Some Context at the Chisenhale Gallery in London, I Need Help at Real Fine Arts in New York, and Anxietina at the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva.