Gregg Bordowitz

Gregg Bordowitz

A new retrospective at the Jewish Museum showcases the artist’s commitment to the fight against fascism and oppression.

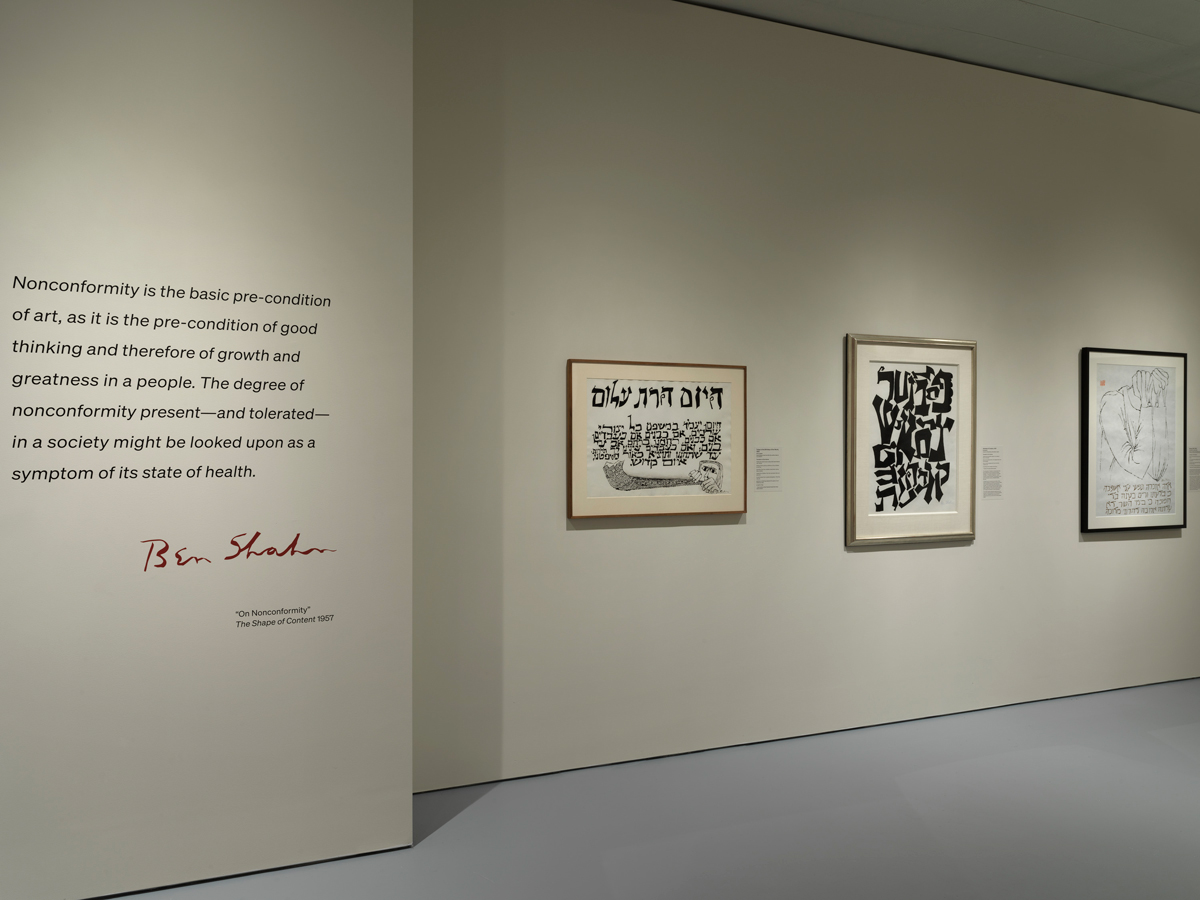

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, curated by Laura Katzman, Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue, New York City,

through October 26, 2025

• • •

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, currently at the Jewish Museum in New York, is the first US retrospective of the artist (1898–1969) in nearly half a century, and features 175 artworks and objects revealing Shahn’s multidisciplinary approach. Dating from the 1930s to the 1960s, these include paintings, mural studies, prints, photographs, commercial designs, and ephemera—all installed in seven galleries taking over the entire first-floor exhibition space of the museum. Pieces are organized thematically according to a loose chronology, mediums mixed. Vitrines in each room are filled with historical documentation and other contextual materials. Curator Laura Katzman is a lively storyteller, vividly unfolding the practice of a committed imagist who mined the developments of nonrepresentational painting to evolve a unique and recognizable style of picture-making.

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured, center, back wall: 1943 AD, ca. 1943. Tempera on pressboard.

Exciting and unique to this show, Katzman’s scholarship presents a thorough appreciation of Shahn’s own photography. Throughout his career, Shahn drew inspiration from an archive of sources collected from media including newspapers and an extensive body of images he took as an RA-FSA photographer traveling the US during the Great Depression documenting lives lived amid poverty and prejudice. Sam Nichols, Tenant Farmer, Boone County, Arkansas (1935), for example, became the source for a canvas of a plaintive man (a figure who reappears in other works) holding his rough large hand to his mouth and chin, regarding the viewer from behind a line of barbed wire, titled 1943 AD (ca. 1943).

Tensely located between hope and despair, each of Shahn’s pieces is a protest testifying to the artist’s abiding belief in a universal ideal of justice. His canon stands as a testament to a seemingly dated but currently attractive humanism—one consistent principle of justice that connects together all struggles against authoritarianism, and wherever a powerless group is subjugated to economic dominance and intolerance by a wealthy few.

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Shahn had immigrated to the US as a child in 1906 with his working-class parents from Russian-controlled Lithuania. Biographical information in wall text tells us that he was a secular Jew for whom biblical knowledge was an important source. In words and pictures, Shahn drew upon Jewish traditions stressing humility in the face of the unknown, as well as the Hebrew Prophets who inveighed against the corruption of kings and their courts, against war and warmongering, against materialist obsessions that mislead people to ignore the greedy causes of poverty. The ethical imperatives of biblical literature direct us to welcome the stranger, and to provide for the poor and orphaned.

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

It’s the religious dimensions of his humanism that proved fecund ground for Shahn’s political commitments. In the painting Second Allegory (1953), an oppressive fiery cloud frames the shape of a downward accusing finger pointing to, pressing on a terrified figure. The Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation loom. Crudely drawn, crystal-like geometric shapes float in the background, perhaps a comment on the technological nightmare of a society “rationally organized toward irrational ends,” as Marcuse so eloquently described the postwar period.

Ben Shahn, Second Allegory, 1953. Tempera on canvas mounted on Masonite, 53 3⁄8 × 31 3⁄8 inches. Courtesy Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. © Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS).

The figure in Second Allegory resembles Job, a character in the Hebrew Bible whose faith is tested through loss and illness. G-d humbles Job with a series of vexing questions, such as “Have you an arm like G-d’s? / Can you thunder with a voice like G-d’s?” The story possibly teaches us that mortals cannot comprehend the vast order of the cosmos: “Can you tie cords to Pleiades / Or undue the reins of Orion?” G-d’s questions to Job—quoted from the Bible in Hebrew—appear calligraphically in a framed gouache-on-paper titled Pleiades (1959).

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured, second from far right: Alphabet of Creation, 1957.

The screen print The Alphabet of Creation (1957) shows the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet jumbled together in Shahn’s highly stylized calligraphy, playfully arranged to maximize an oscillation between positive and negative spaces. Jewish mysticism teaches that G-d created the world enlisting the help of the alphabet. Here, every artwork takes a recrudescent form of protest on behalf of creation. In Shahn’s oeuvre, vitality, like justice, is a renewable constant.

Surrealism was admired but rejected by Shahn, because he thought that the unconscious cannot create art “as the very act of making a painting is an intending one.” For him, intention was the determining factor of composition. Still, as viewers in the museum galleries today, we are all left to contemplate our own unconscious associations. One memorable photograph shows a storefront—Untitled (Lower East Side, New York City) (1936). The plate-glass window of a kosher butcher displays a poster for a production appearing at the Palestine Theatre on Clinton Street, starring Bing Crosby and Ethel Merman. The word Palestine signaled my attention.

Ben Shahn, Untitled (Lower East Side, New York City), 1936. Gelatin silver print, 7 15/16 × 10 1⁄8 inches. Courtesy the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

In 1936, Palestine was a British-occupied region. The picture was taken well before the forcible displacement of a majority of the Arab population in Palestine, executed in 1948 to establish the state of Israel. No work of art in this exhibition refers to the Israeli state. However, Shahn’s story is entangled with that history, and our historical present.

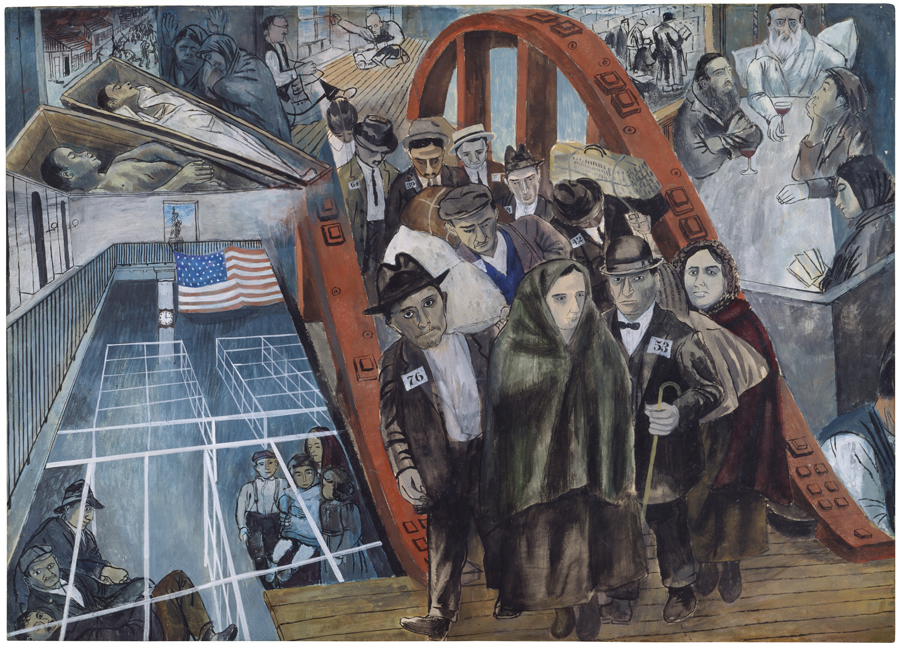

Ben Shahn, Study for Jersey Homesteads mural, ca. 1936. Tempera on paper on Masonite, 19 1⁄2 × 27 inches. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

Consider Study for Jersey Homesteads mural (ca. 1936), which presents European Jewish immigration to the United States as a secular, modern-day exodus. Jersey Homesteads was a cooperative town intended to house Jewish garment workers, relocating from New York sweatshops and tenements. Somber immigrants flee anti-Semitic conditions in Europe for an unknown American future. The Statue of Liberty appears in the distance. Jews pray in Jerusalem, another refuge for them outside Europe, but New York City is the primary destination. Shahn merged the first wave of Eastern European immigration to the US (1880s–early 1900s) with Nazi-era emigration from Germany.

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, installation view. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Nonconformity rests on the very fault line divisively policing what can and cannot be stated in New York art institutions today. Artists can remain committed to social justice movements, but no one is permitted to exhibit art expressing dissent against US policy subsidizing Israel’s war crimes. Support for Palestinians—and Palestine—receives swift condemnation and censorship.

The show is not so much an answer to current artistic problems as it is a set of directions, possible routes pointing in the direction of one’s conscience. Shahn engaged directly—and historically—in anti-fascist struggle, aligning his labors with the downtrodden and oppressed. He championed the struggles of workers, unionists, and immigrants against xenophobia, racism, and imperialism. His craft brought an urgency to pictures still standing now as place-markers for decisive historical turning points. Nonconformity is a crucial study of an artist who successfully combined passionate—often conflicting—commitments to both social justice and to the integrity of his vocation.

Gregg Bordowitz is an artist and writer living and working in New York City.