Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

In a near-lifetime confined to an asylum, uniforms, sheets, and blankets become material for creations driven by spiritual compulsion.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, installation view. Courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas. Photo: Arturo Sánchez.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, curated by Aimé Iglesias Lukin, Ricardo Resende, and Javier Téllez, with Tie Jojima, Americas Society / Council of the Americas, 680 Park Avenue, New York City, through May 20, 2023

• • •

The drive to create can be an exquisite and exhausting burden. In the short documentary video included in the Americas Society exhibition of Afro-Brazilian Arthur Bispo do Rosario (known as Bispo, 1909–89)—the first US solo show dedicated to his five decades of impassioned handiwork—he describes the throbbing spiritual compulsion that gave rise to his astonishing embroideries, inventories of accumulated objects, and crafted replicas. The voice that speaks through him “tangles me up,” Bispo says, as he confesses that his divine vision is more of a torment and demand than a gift. That relentless obligation, which propelled his activities and thoughts both day and night, led to the production of complex textile estandartes (banners wielded at religious festivals and carnival parades) and altar-like assemblages that he did not categorize as art but that, since his death, have had a vibrant, influential afterlife in museums, biennales, and exhibition spaces.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, installation view. Courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas. Photo: Arturo Sánchez.

As a young man, Bispo trained in the Brazilian navy as a semaphorist, received minor renown as a professional boxer, and worked as a domestic servant for a family in Rio de Janeiro. On December 22, 1938, he had a transformative revelation that he was a messiah, and just days later was committed to the National Hospital for the Insane. He was subsequently transferred to the brutally dehumanizing psychiatric institution Colônia Juliano Moreira, where he spent much of the rest of his life in a cell that became a makeshift studio and gallery, resourcefully unraveling the asylum’s uniforms (hence the prevalence of faded blue thread throughout his work) and stitching on hospital-issued sheets and blankets. His goal was to reconstruct everything on Earth, and he pursued this sweeping ambition by making more than a thousand pieces; some are small and modest, while the larger works have an incantatory intricacy that approaches the grandiosity of his mission.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, installation view. Courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas. Photo: Arturo Sánchez. Pictured, right: Untitled [Manto da apresentação (Annunciation garment)], no date.

In the exhibition’s opening room, a sampling of photos, garments, and documents emphasizes the exuberant scope of Bispo’s all-encompassing project as well as the physical confinement he was constantly negotiating. His fringed, ritualistic “annunciation cloak,” to be worn when he presented himself to God, is lined with the names of women who would accompany him on this journey. Nearby, his hospital ID card shows him squinting (from the sun? the bright flash of the camera?) next to typed words classifying him as both indigent and paranoid schizophrenic—a diagnosis fraught with starkly racialized implications, notes Jonathan Metzl in his book The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia became a Black Disease. Though Metzl was writing about histories of mental hospitals in the United States, his observations extend to the Brazilian context, where descendants of enslaved Africans, such as Bispo, comprise a majority of those held in carceral facilities that corral people experiencing homelessness and mental illness.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, installation view. Courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas. Photo: Arturo Sánchez.

Showcasing Bispo’s productions against walls half-painted a lightly nauseating hospital lilac, curators Aimé Iglesias Lukin, Ricardo Resende, Javier Téllez, and Tie Jojima underscore the inventive material basis for his work alongside the psychic entrapment and bodily captivity that gave rise to it. He was granted the privilege to generate his creations because he helped the guards restrain unruly patients and was thus afforded some liberties within the colony. A selection of his found-object collections, which feature neatly arranged accumulations of bus tokens, shoes, combs, cutlery, and metal cups, demonstrate the range of things he had access to and was allowed to keep. Such paradoxes—freedom within imprisonment, order out of chaos—guide the logic through which Bispo filtered his experiences and wrought his fiber-based marvels.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, installation view. Courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas. Photo: Arturo Sánchez.

During his years of detention, Bispo constructed dozens of reproductions of objects out of fabric, wood, metal, and cardboard, helpfully labeling them, since their slightly lumpy contours don’t always immediately register: hammer, lamp, paint roller, compass. He was riveted by tasks of archiving and understood that cataloging can be effective via text as well as image: banners list everyone he ever met and every name that starts with the letter A, while others are schematically drawn compendia of navy ships or aerial-view maps of the countryside and the nation. Many of them hint at the world outside the walls of Bispo’s cell, a world he accessed through the newspapers that he regularly consulted; for example, they were the source for a series of Miss Universe sashes that are the same scale as actual pageant finery but are crowded with idiosyncratic geographical elements. Bispo’s embroidery, though elaborately detailed and deftly executed, is composed of relatively simple stitches that evidence countless hours of minute, hand-cramping labor. Some of the blankets have stains or are stamped with the name of the hospital; when on display at the 1995 Venice Biennale, the garments he had worn as daily uniforms were so odiferous that they had to be laundered.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, installation view. Courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas. Photo: Arturo Sánchez. Pictured: Untitled [Navios de Guerra (War ships)], (detail) no date.

Indeed, since it first began circulating in the contemporary art world, Bispo’s work has raised questions about what it means to “clean up” his history, to extract his creations from the state apparatus in which they were made and redefine them as art. Are we imposing a decontextualized aesthetic framework onto these pieces or are we elevating them to their rightful place? Brazilian art institutions have long engaged in a complicated conversation about “arte popular” and makers who forged ahead on the periphery, or in the complete absence, of art markets; and scholars of Brazilian art, such as Kaira M. Cabañas, have nuanced overly simplistic terms, like self-taught, outsider, or folk, that are still prevalent in the US. Seeing Bispo’s work within this carefully framed exhibition sheds light on these unresolved issues of categorization. Grappling with Bispo’s oeuvre also gives texture to another stale formulation, that of embroidering and sewing as naturalized “women’s work” rather than as intentionally degraded gendered labor. The patriarchal devaluing, and hence feminizing, of needle-based textiles helps account for why so many men who are queer or otherwise marginalized have turned to fabric and thread as a creative outlet (José Leonilson and Feliciano Centurión both come to mind).

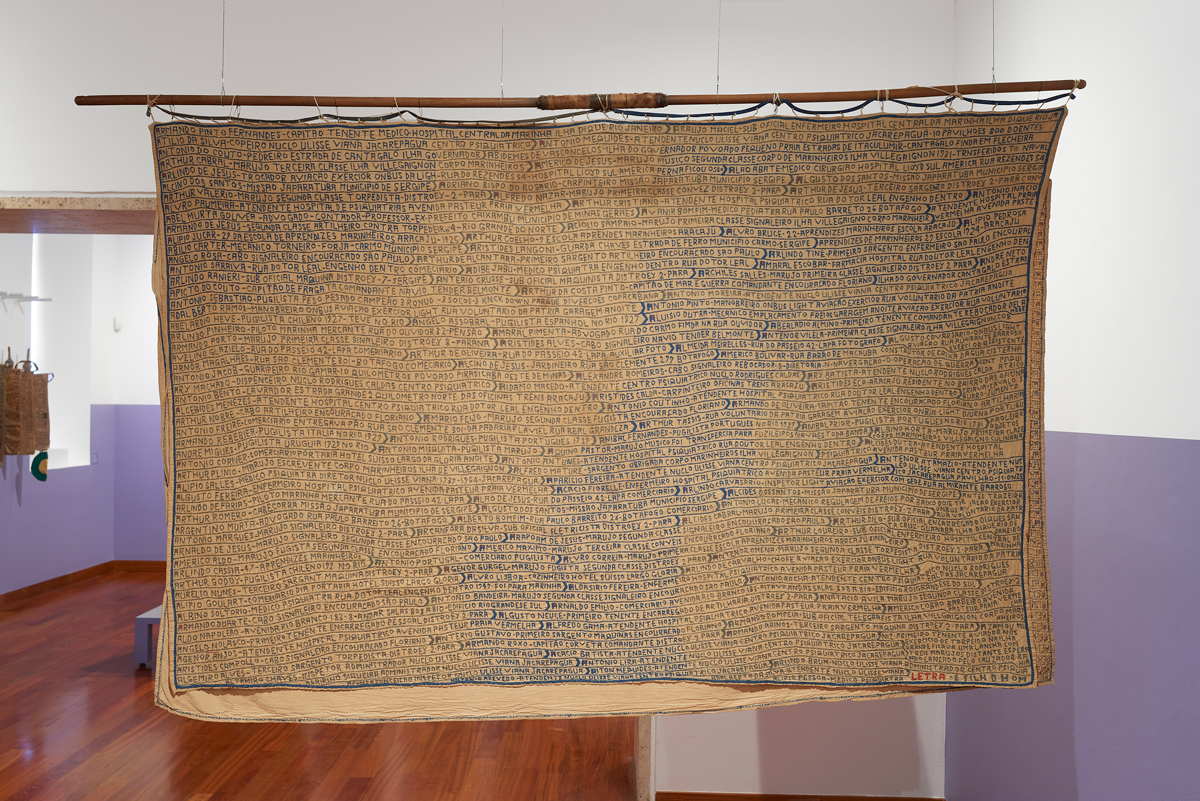

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth, installation view. Courtesy Americas Society / Council of the Americas. Photo: Arturo Sánchez. Pictured: Untitled [Dicionário de nomes letra A (Dictionary of names letter A)], no date.

Embroidery is fundamentally a maneuver of piercing through, and in Bispo’s hands this act suggests a repeated puncturing of the threshold between realms—the earthly and the heavenly, the quick and the dead, the logical and the irrational. His life’s project hints at a greater truth, which is that the whole world is crafted by laboring bodies: by hummingbirds who diligently weave together nests from spiderwebs, by employees toiling in apparel factories to churn out clothes, by incarcerated people in prisons forced to manufacture goods for no pay, all of whom make and make and make not because they want to but because they have to.

Julia Bryan-Wilson’s most recent book, Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture: Drag, Color, Join, Face, will be released in June 2023. Along with teaching at Columbia University, she is Curator-at-Large at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo.