Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

Gringolandia gets more style than substance in

Appearances Can Be Deceiving.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, through May 12, 2019

• • •

André Breton famously referred to the art of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo as “a ribbon around a bomb.” The fear, upon reading the press release for Kahlo’s retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, Appearances Can Be Deceiving, which features her clothes alongside her artworks, is that the exhibition would sacrifice the latter for the former, undermining Kahlo’s artistic and political achievements with an emphasis on her personal adornment. And the show’s opening gambit—a large projection of a color film, the camera panning from the artist’s face down the length of her body—did little to dispel this worry, one that grew to full-blown dismay by the time I reached the concluding gallery, where an abundance of almost twenty outfits was set next to a paltry three paintings.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

Navigating Kahlo’s extraordinary fame and popular appeal requires no small measure of curatorial dexterity, and despite its shortcomings, the show does a nimble job of highlighting her communist commitments, her indebtedness to folkloric and native visual practices, and the complexities of her mezcla identifications. Especially welcome comparative materials include a wealth of photographs from her father’s studio in Mexico City, a video of Trotsky’s Moscow Trials speech from 1937, prints by Carlos Mérida of traditional regional garments that were often depicted in Kahlo’s self-portraits, a wall tightly hung with painted metal votive retablos, and indigenous artifacts such as Olmec and Colima ceramics.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

The exhibition includes over three hundred objects, and though the number of actual artworks by Kahlo is relatively small, what is here is riveting, including lesser-known drawings such as her biting anti-capitalist Lady Liberty (Workers of the World, Unite) (ca. 1949), a speculative revision in which the Statue of Liberty holds a bag of money and brandishes an exploding atom bomb. Meticulous still lifes, such as The Bride Who Becomes Frightened When She Sees Life Open (1943), and careful attention to vibrant fruit, animals, and dolls across her oeuvre display her density of imagination, and gesture to a worldview that did not make hard distinctions between animate and inanimate matter.

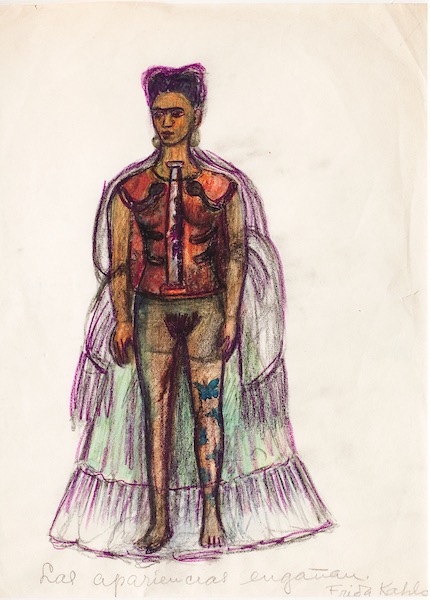

Frida Kahlo, Appearances Can Be Deceiving, n.d. Charcoal and colored pencil on paper, 11 ¼ × 8 inches. © 2019 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust / Artists Rights Society.

When the exhibition originated at the Victoria and Albert Museum, it was subtitled Making Her Self Up, signaling a certain canniness around the artist’s cultivated image, one that was eagerly consumed in what she called Gringolandia. The Brooklyn title, Appearances Can Be Deceiving, is taken directly from a remarkable drawing of Kahlo’s that depicts, like an X-ray, her signature long skirt covering a body marked by accident, illness, and medical intervention. It’s a punchy title, but in fact the Brooklyn exhibition promulgates exactly the opposite thesis, which is that Kahlo’s appearance functions in effect as a direct portal into her artistic practice. Not only does her appearance not deceive, but the rhetoric of this exhibition insists that it reveals the truth or authenticity of her artistic vision, or even, in a somewhat straightforward way, that it constitutes her art. Rather than emphasize that her dresses were part and parcel of a kind of keen self-invention (“making her self up”), the wall labels claim that her look was “an integral part of her life, her art, and her identity.”

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

The Kahlo show joins another current New York blockbuster dedicated to a twentieth-century artistic icon whose art was indelibly shaped by bodily vulnerability—the Andy Warhol exhibit at the Whitney. The contrast is instructive, and unmistakably gendered. In the Whitney retrospective of Warhol, there are none of his wigs or facial unguents (though they have been included in other shows). But the Kahlo exhibit teems with collections of her personal effects, among them jewelry, perfume, bandages, and medicines, creating an awkward mix of unlike objects. So intense is the fetishization of every facet of Kahlo’s admittedly magnetic visage that the Brooklyn exhibition includes a vitrine containing her lipstick, blush, and bottles of nail polish. “Revlon was her favorite brand” trumpets the label rather shamelessly—Revlon is one of the exhibition’s sponsors.

A conceptual case can be made for the display of the cast-off plaster medical corsets that she painted and kept, for these illustrate Kahlo’s artistic ingenuity and demonstrate her adept manipulation of materials. Indeed, these corsets—with a red hammer and sickle painted over her heart, or a fetus tucked into the space of her womb—feel like the core of a different show, one in which questions about gendered, raced, and disabled bodies as they inform Kahlo’s painterly concerns are held in better balance.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

The counterargument asserts that these artifacts and clothes made her who she was, and that by putting her possessions on view, we are granted special insight into her art. If these are insights, they are banal; yes, our belongings shape our aesthetic sensibilities, and we decide to fashion ourselves in accordance with how we desire to present ourselves to the world. But just because she was deliberate about her appearance (many people are) and painted self-portraits of herself wearing clothes (again, this is hardly exceptional) does not guarantee that the garments themselves are interesting.

Judging by the rapturous publicity apparatus surrounding the V&A version of this show, and of the recent exhibition, also at the Brooklyn Museum, of Georgia O’Keeffe’s clothes (which, unlike Kahlo, O’Keeffe mostly designed and made), museums have no problem with focusing far more on the fashion of well-known female artists than on their paintings. These shows have scholarly merit, are buttressed by ample research, and granted thoughtful installation by curators whose work I deeply respect. But until I see equivalent art-institutional attention dedicated to the personal style of male artists—Accessorizing Joseph Beuys: Hat, Cargo Vest, Messenger Bag; Salvador Dalí’s Mustache (sponsored by Dalí’s Preferred Brand of Corporate Mustache Wax)—I will continue to rail against this trend. Kahlo’s art has something urgent to tell us at this moment, when museums are being called to decolonize their hiring practices and their holdings, and artist-activist Nan Goldin is bringing attention to how the art world profits from the opioid crisis. This visibly mestizo, bisexual, far-left Mexican woman lived a life in pain, and Kahlo’s paintings and drawings at their best open up space for a complex politics of representation, because her art was conditioned by her circumstances but also refuses to be fully confined to them. Ultimately, the show’s theme dilutes but cannot defuse the power of her art. Kahlo’s bomb explodes and explodes, and it tears those ribbons to shreds.

Julia Bryan-Wilson, winner of the 2019 Frank Jewett Mather Award for Criticism, teaches at UC Berkeley and was recently appointed adjunct curator at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo.