Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

Seven works by the late artist invite deceleration and

contemplative witnessing.

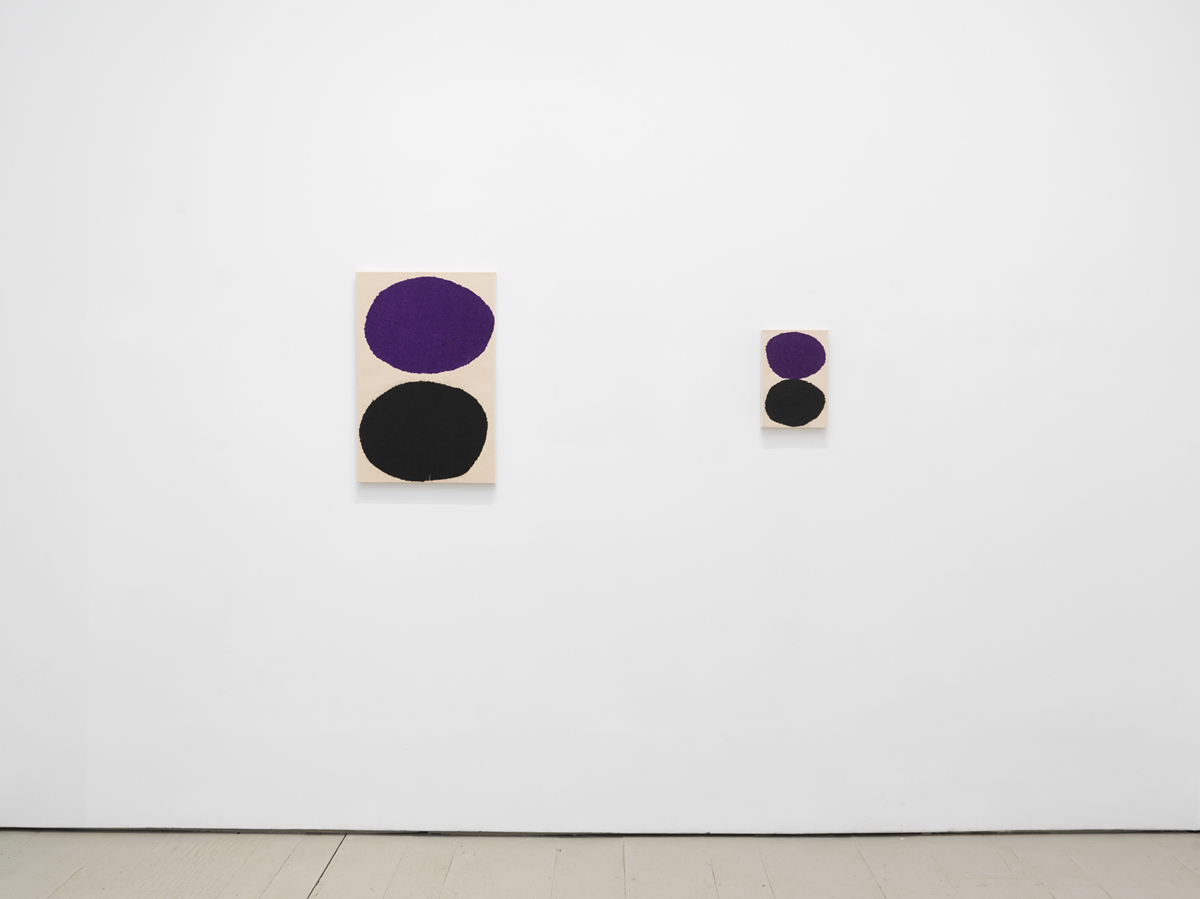

Nancy Brooks Brody: Ode, installation view. Courtesy Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery.

Nancy Brooks Brody: Ode, Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, 87 Franklin Street, New York City, through May 11, 2024

• • •

“O Blue come forth / O Blue arise / O Blue ascend / O Blue come in.” These invocations to pure color as portal and protagonist resound at the beginning of Derek Jarman’s monochromatic experimental film Blue. Shot in 1993, as the artist’s vision was declining due to the debilitating effects of HIV/AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis, Blue was Jarman’s last work. With its commitment to queer abstraction and the expressive potentials of chroma, Blue furnishes a key reference point for Nancy Brooks Brody’s breathtakingly beautiful exhibition Ode. Comprising seven pieces, the show, now on view at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, is a spare, lyrical glimpse into their exquisitely careful methods of making and, as with Jarman’s film, a testament to the power of art created in the face of illness. Brody succumbed to ovarian cancer, at the age of sixty-one, in December 2023, and the works here were crafted in the final year, indeed the final days, of their life.

Each piece in the exhibit features two ovoid forms composed of torn tissue paper; monumental in appearance, they float one atop the other, hugging the edges of the raw canvas to which they are affixed. Ranging in size from an intimate twelve inches high to a nearly human-scale five feet tall, these tissue-paper paintings command the small gallery space with their rigorous attention to the lure of saturated colors that at times bleed or buckle. All the canvases are hung vertically, and in all except the final piece, Joy, For Joy (2024), a black oval fills the bottom half, while a colored oval dominates the upper register. We encounter daffodil-egg-yolk yellow, poppy-cardinal-crimson, slate-cloud-ocean gray. But descriptors that draw only from the natural world are inadequate, for Brody’s yellow also has an industrial feel, and their blue is almost chemically vivid. This touch of flamboyance around hue serves to highlight the work’s compositional restraint. The artist used ink to dye plain white sheets of tissue paper for the largest works, and the black has an unusual velvety depth that plays off its companion colored form, which reveal the grain of the canvas beneath.

Nancy Brooks Brody, Vernal Yellow, 2023. Tissue paper on canvas, 12 × 8 inches. Courtesy Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery. Photo: Jenny Gorman.

Handled with the greatest of care, each stacked orb is made out of a single piece of tissue, ever so gently pressed down, with adherent brushed along its underside and over its surface to ensure fixity. At moments, the fragile tissue has split or wrinkled, or has been worn through. These little incidents of shredding, coupled with the feathery fraying along the torn edges of the ovals, are tender reminders of the delicacy of Brody’s touch.

The works’ materiality recalls both vernacular practices of decoupage and the wheat-pasted posters Brody produced as part of the AIDS dyke activist collective fierce pussy, alongside Zoe Leonard, Carrie Yamaoka, and Joy Episalla. (Episalla and Marisa Cardinale co-organized this exhibition with the gallery, and art historian Jill H. Casid penned an insightful essay for its catalog). Generated quickly and collaboratively and then hung in the street as urgent calls, fierce pussy’s feminist posters were transient: inevitably scraped off, vandalized, rained on, pasted over, or ripped down. Brody’s 2023 pieces, with their fissures and tears, echo both the imperative to create and such creation’s ephemerality. They are also a reminder of how much Brody was committed to several simultaneous kinds of artistic communication throughout their life, from the direct address of fierce pussy’s text/image statements, to investigations into the dancerly gestures of queer choreographer Merce Cunningham, to untethering making from the demands of representation.

Nancy Brooks Brody: Ode, installation view. Courtesy Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery.

Queer abstraction can mean many things, including the right of refusal, by encoding our yearnings so they are illegible to the surveilling gaze. If Brody’s canvases evoke surrogate bodies (for flesh is made of tissue), they also resist such readings. When contemplating Ode, I thought of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Double Portrait) (1991), an endless paper stack in which two circles kiss, as well as of paintings by Etel Adnan, in which stripped down geometries suggest geopolitical landscapes. The drawn glyphs in Adnan’s searingly relevant book-length poem The Arab Apocalypse (1980) provide a further precedent for Brody’s queer abstraction and the use of nonrepresentation to address the unspeakable, such as disaster, desire, and death. Adnan begins, like Jarman did, with an incantation of color: “A yellow sun A green sun . . . a red sun a blue sun.” I see Adnan’s multi-chromatic suns in Brody’s forms, rising above inexhaustible black wells.

Nancy Brooks Brody: Ode, installation view. Courtesy Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery. Pictured, right: Vernal Violet no. 2, 2023.

In previous series, the artist had also explored how subtle and surprising interventions in space—such as a thin line of metal embedded into the gallery wall—could beckon viewers toward more contemplative modes of witnessing. The installation of Ode as a corpus encourages similar decelerations, and the hang in particular invites speculation about the adjacency of two canvases that each feature purple, but are of different sizes, and thus elicit direct comparison. Uniquely among this selection, in the smaller work, Vernal Violet no. 2, the two ovals come together in the middle, creating a short seam of provocative overlap. This moment when the two circles meet is vital, for it asks us to consider why such a meeting occurs here—indicating a rare instance of connection as the fibers mutually clasp. Elsewhere, the negative space between and around the fuzzy forms has been thoughtfully negotiated, and it emphasizes that Brody’s twosomes matter as these works grapple with the pair as a charged configuration. The twinned colored shapes exist as entities within a world in which the couple (parent/child or sibling/sibling or self/other or lover/lover) is asked to hold so very much. But also: how easily the duo can disintegrate. How suddenly we can spin apart. How much damage we can do with our hands as we try to secure things into place.

Nancy Brooks Brody, Joy, For Joy, 2024. Tissue paper on canvas, 60 × 38 inches. Courtesy Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery. Photo: Carrie Yamaoka.

Within art history, the assignation of portent to an artist’s last work is a contested, trite cliché—why should a wheat field of crows painted by Vincent van Gogh be laden with extra significance simply because it might have been his final piece? But within a queer crip-disability framework, in which an artist is actively confronting the impermanence of the body or thematizing their own mortality, such a lens is critical. (A death due to ovarian cancer, like a death due to HIV/AIDS, is an indictment of the medical establishment for its failures to prioritize the health of women, nonbinary, trans, and queer people.) Brody’s last works demonstrate the intensity that can be unleashed when artists set themselves a set of strict operations within which to maneuver. Their always sophisticated means of making are here on ample display, along with a newfound exuberance. Joy, for Joy, which was partly executed posthumously by Brody’s friends according to the artist’s exacting specifications, is the only tissue painting in Ode with no black orb; instead, a vibrating blue pools under a gossamer gray. But like the others in this series, it feels stubbornly and defiantly alive, with blue pigment seeping out beyond the confines of its borders, and the gray riven with veins that seem to pulse—endless suns in whose unconventional light we bask.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is Professor of Contemporary Art and LGBTQ+ Studies at Columbia University. Her most recent book is Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture: Drag, Color, Join, Face (Yale University Press, 2023).