Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

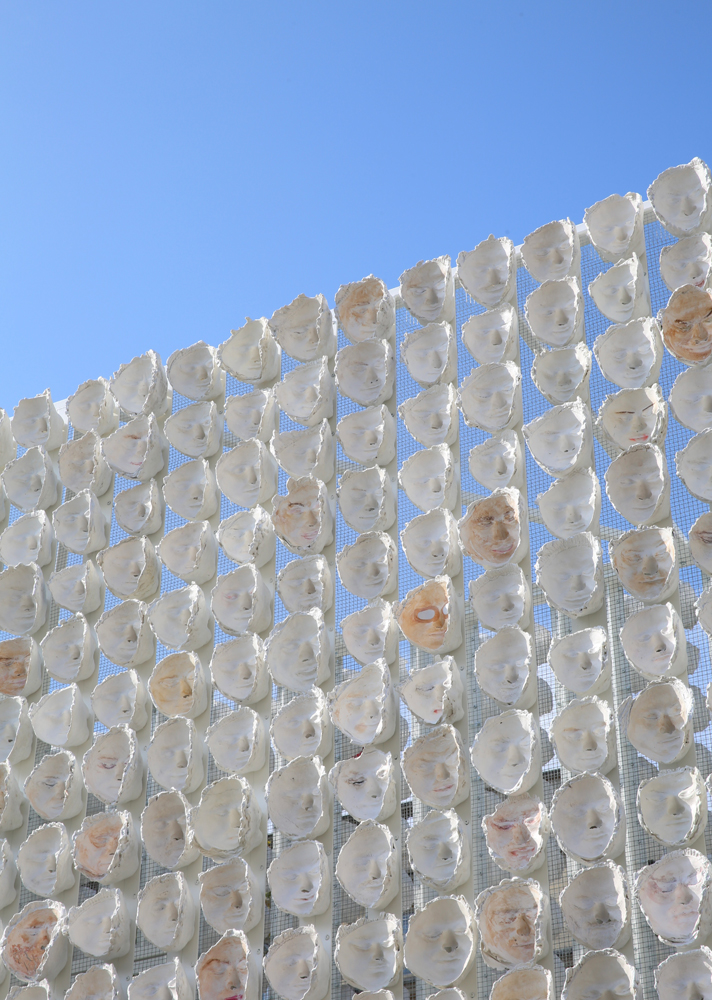

In 726 life masks of trans and nonbinary people, a spectacle of death.

Teresa Margolles, Mil veces un instante (A Thousand Times an Instant), 2024. © James O Jenkins.

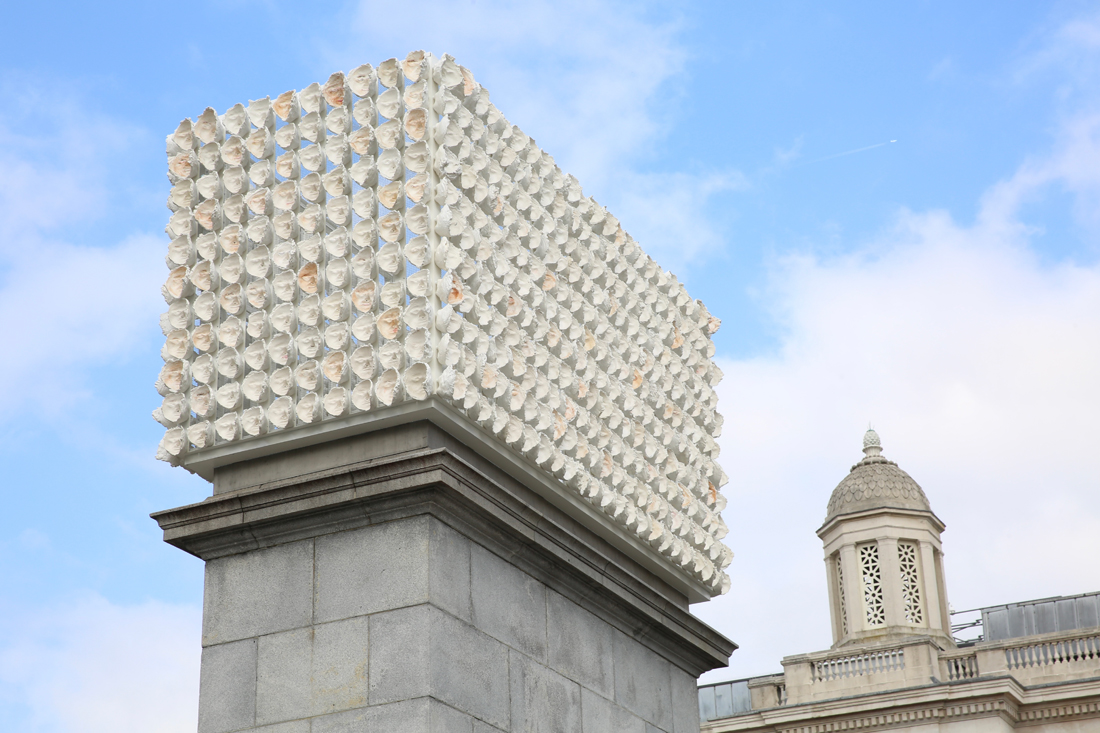

Teresa Margolles: Mil veces un instante (A Thousand Times an Instant), Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London, through September 2026

• • •

A tzompantli—commonly translated from classical Nahuatl as “skull rack”—is a gridded, scaffold-like device for displaying human heads that appears in several ancient Mesoamerican cultures. Some tzompantli were sculpted out of stone and erected to threaten adversaries; others were constructed of actual skulls, trophies of imperial conquest or ritual sacrifice, set into stucco. In 2015, near the Templo Mayor in present-day Mexico City, archaeologists unearthed part of the Aztec Huey Tzompantli: a tower made of more than six hundred skulls, with geometrically stacked visages interrupted by irregular teeth and cheekbones emerging from the surrounding caked lime.

Nearly a decade later, in fall 2024, Mexican feminist artist Teresa Margolles unveiled her tzompantli-inspired sculpture Mil veces un instante on London’s fourth plinth. The fifteenth artist commission to occupy the long-empty pedestal that anchors one of the four corners of Trafalgar Square, Margolles’s work is comprised of life masks of 726 trans and nonbinary people from Mexico and the UK who volunteered to let the artist cast their faces in plaster. The work is billed as a memorial to Margolles’s friend and collaborator Karla La Borrada (the text plaque names her only as “Karla”), a trans-woman singer, activist, and former sex worker who was brutally killed in Ciudad Juárez in 2015. Plaster is a fragile medium, and, exposed to the elements over a two-year span, the project will gradually disintegrate. Eight months into its run, the effects of time on the piece are already evident. Jagged edges have started to noticeably erode, but visible traces of makeup that had rubbed off onto the negative sides of the casts were still detectable—little wisps of false eyelashes adorning eye sockets, swashes of blush coloring some cheeks, and full beats of brown foundation adding variegation to the otherwise uniform, ghostly white pallor of the faces.

Teresa Margolles, Mil veces un instante (A Thousand Times an Instant), 2024 (detail). © James O Jenkins.

Margolles, a former forensic pathologist and participant in the 1990s punk death-metal performance collective SEMEFO, has long investigated spaces of death and the politics of flesh. Though working across genres, she is at her most incisive as a photographer and a choreographer of immersive environments, such as her renowned 2009 Venice Biennale pavilion representing Mexico, in which relatives of those killed by narco violence mopped the floors with diluted blood. Her sculptures—like the corpse of a stillborn fetus contained in a concrete block (Entierro/Burial, 1999) or the preserved tongue of a murdered teenager displayed on a delicate stand (Lengua/Tongue, 2000)—are often less successful, verging on a gimmicky literalness that is overly reliant on shock factor.

Teresa Margolles, Mil veces un instante (A Thousand Times an Instant), 2024. Courtesy Julia Bryan-Wilson.

And Mil veces further exacerbates doubts about Margolles’s adeptness as a sculptor. The architecture of the fourth plinth demands a solution attuned to dimensionality and viewing in the round, but her cubic arrangement blends in innocuously with the surrounding space. Unlike the Aztec heads, which confront the viewer, Margolles’s decision to mount the masks facing inward—secured to a mesh of wire—rather than outward means we see a series of cavities, not the defined features of specific persons. As a whole, the sculpture does not activate the monumentality of the pedestal nor address this ideologically charged site (the square celebrates a British naval battle). The most memorable plinth commissions have been those by Rachel Whiteread and Michael Rakowitz, though they approached the task from entirely divergent perspectives. Whiteread apprehended the empty plinth as void, inverting the base and duplicating it in transparent resin to formally emphasize the material presence of its absence. Rakowitz grappled with the urban space of Trafalgar Square as a microcosm of empire, creating a magnificently executed Assyrian winged bull sculpture clad with Iraqi date syrup cans, suggesting continuity in the wake of histories of erasure. His Lamassu opened a conversation with the Square’s heroic equestrian statuary, which commemorate the leaders who set the stage for current wars and the widespread destruction of Iraqi cultural heritage.

Teresa Margolles, Mil veces un instante (A Thousand Times an Instant), 2024. © James O Jenkins.

Like Rakowitz, Margolles evokes a past form to make a comment on contemporary conditions. But the tzompantli is an odd choice for our current moment of escalating state-sponsored hatred toward trans women and gender-nonconforming folks: the ancient racks amassed and displayed victims at least in part as a strategy to induce terror. Moreover, despite the artist’s careful attention to cast distinct faces, the sitters’ individual personhood gets lost in the repetitive, modular format. Given the plinth’s height, it is impossible to observe them closely. Not only that, but Margolles’s piece traffics in a kind of gleeful necrophilia that threatens to overwhelm public discourse about trans women, especially trans women of color, who are too often defined by their mortality. Though they are more vulnerable by far than white trans men, the misleadingly universalized statistic that Black trans women have an average life expectancy of only thirty-five due to suicide and homicide is so widely circulated, trans activists caution that it might function as a self-fulfilling prophecy. The title of Mil veces, too, suggests that tragic and untimely demise is the single overriding condition of trans life, taking place “a thousand times an instant.” As an ephemeral anti-monument organized around the tzompantli, the work feels hermetic and defeated as it participates in spectacularizing the inevitability of trans death.

Teresa Margolles, Mil veces un instante (A Thousand Times an Instant), 2024. Courtesy Julia Bryan-Wilson.

Margolles’s plinth piece was on display in April 2025, when the UK Supreme Court handed down their cruel decision that trans women are not legally women. In short, trans women have been ruled socially dead, nonexistent in the UK—a place grossly out of step with the vast majority of global feminist movements, which are staunchly trans-inclusive. A few streets away from Mil veces, a kitschy bronze statue of a certain fictional boy wizard flies on his broomstick. He is the invention of transphobic author J. K. Rowling, whose hateful social-media rantings have stoked a large, fear-based following. The two sculptures sit in physical proximity, rival markers of this moment of escalating threats to justice—and the simple right to be—for trans and nonbinary people. (In the US, the Trump administration is also clawing back hard-won protections.) The Margolles sculpture has the potential to resonate alongside the trans-rights rallies and demonstrations that have erupted since the court ruling. But her faces, ambivalently depicting living persons who are nonetheless glorified as dead, are turned away from the scene of the crime, muted, with their eyes closed.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is a professor of art history and LGBTQ+ Studies. She is also Curator-at-Large at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, where she recently co-curated the exhibition Histórias LGBTQIA+/Queer Histories.